Ghana’s cocoa industry has achieved consistent growth, but low global market prices, a lack of management transparency, and a shortage of younger farmers loom as major challenges, according to The Cocoa Coast: The Board-Managed Cocoa Sector in Ghana, a new IFPRI book.

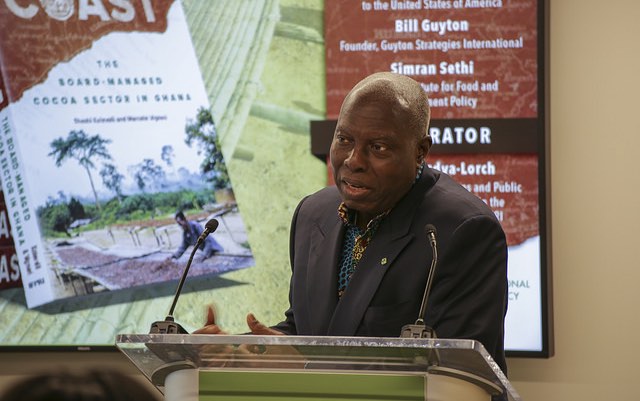

Panelists discussed the book—by IFPRI Senior Research Fellow Shashidhara Kolavalli and independent researcher Marcella Vigneri—at a recent launch event in Washington. In Ghana, The Cocoa Coast has focused attention on the industry’s successes and stimulated critical dialogue on its problems and potential reforms.

“By pushing this book [we hope] society can be awakened to the potential of cocoa for the nation as well as our farmers,” former Ghana President John Agyekum Kufuor noted at an earlier book event in Accra.

Unlike other African countries, Ghana did not follow the free-market recommendations of the “Washington Consensus” and liberalize its cocoa industry, which is overseen by the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD). “What we are really trying to do in this book is to examine how Ghana has been able to manage its cocoa sector successfully through a quasi-government-run organization,” Kolavalli told the Washington panel.

“Cocoa is the mainstay” of Ghana’s economy and has been since the colonial era,” Kufuor observed. Today, Ghana produces up to 800,000 tons of premium cocoa annually, second globally only to Cote D’Ivoire. This combination of history and economic clout places cocoa at the center of the Ghanaian agricultural identity. Thus, the saying: “Ghana is cocoa and cocoa is Ghana.”

Despite the industry’s global scale, cocoa farmers and their families remain overwhelmingly poor. Farmers make as little as six cents on each U.S. dollar spent on a chocolate bar, and many of them live on $2 per day, according to panelist Simran Sethi, a food journalist and fellow at the Institute for Food and Development Policy. “People pay for one bar [of chocolate] what some farmers get for quarter of an acre,” noted Barfuor Adjei-Barwuah, Ghana’s ambassador to the United States.

It is not for want of industry, soils, or craftsmanship that the cocoa sector lags in paying producers equitably, Kolavalli said. Systemic issues with COCOBOD —including a lack of transparency, mismanagement, and questions over its share of cocoa income—play a role. The book’s key recommendation is the need for greater accountability and transparency in how the surplus amassed by COCOBOD is managed and allocated.

Nevertheless, the board has made significant progress increasing productivity and reducing poverty among cocoa producers over the past decade, Kolavalli noted.

Adjei-Barwuah argued that the structure of the international marketplace—in which chocolate manufacturers buy cocoa at low prices and then make profits further along the value chain—is the core of the inequity problem. “When the price is being fixed on the so-called international market, we are never there,” he said. “If that is not looked at, no matter the changes of the administration, the share that goes to the farmer will always be lower.”

To adequately support farmers, there must be critical dialogue about increasing international prices, panelists agreed. Sethi said she was disappointed at the apathy manufacturers typically express when asked what they can do to help improve the economic plight of cocoa farmers. “What this requires is a system change, and a returning of power back to producing countries,” she said.

Bill Guyton, founder, Guyton Strategies International, suggested that COCOBOD partner with the Cote D’Ivoire cocoa industry to advocate for higher prices, given that together, the two countries produce more than half the global supply.

Ghana’s industry faces significant internal challenges as well. “Low productivity, lack of innovation, and low incomes” are discouraging Ghanaian youth from entering the industry, the book says. The unforgiving global market and the absence of accountability also put off young people. Cocoa farming is neither prestigious nor profitable.

“My father was a cocoa farmer [in Ghana] and since the day he died, I have never been back to the cocoa farm,” said one member of the audience.

The industry must work to change attitudes, Sethi said: “This idea—that the farmers who do this are a bit low status, that they are aging farmers, and that the hope they have for their children is to get out of cocoa farming—is something that must be transformed.”

Another promising future course for Ghana’s cocoa industry lies in diversifying beyond agriculture into manufacturing, Kufuor said at the Accra launch: “Instead of looking at cocoa as a primary raw material, we may also think about making use of its health and cosmetic attributes to produce value-added products.”

Shelleka Darby is an IFPRI Communications Intern.