Nearly one out of five people globally rely on some form of assistance to meet their food needs, and the debate continues to rage over which delivery mechanism is most effective: Food, vouchers or cash transfers. At the recent launch of the World Bank book, The 1.5 Billion People Question: Food, Vouchers, or Cash Transfers?, hosted by IFPRI, participants explored the move towards cash-based transfers over the last few decades.

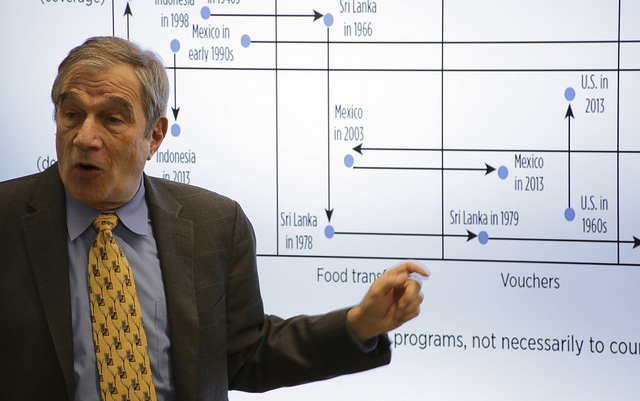

“Programs and policies don’t just spring out of oceans like Aphrodite,” said Harold Alderman, co-author and senior research fellow at IFPRI. Rather, they evolve depending on national or local needs and political contingencies. Despite extensive evidence that cash-based transfers save between 13 and 23 percent of administrative costs as compared to food-based or in-kind transfers, a general transition to cash-based transfers may not be linear as food transfers continue to coexist in countries that provide cash transfers.

“In countries with large shares of the population in agriculture, subsidies and transfers allow both price supports to producers and affordable consumer prices,” said Alderman. He provided examples from the experience of countries including India, Sri Lanka, Mexico, Egypt, Indonesia, and the United States, some of which provide both cash and food transfers including targeted supplements to improve nutrition. However, there are challenges related to poor targeting, data and monitoring; commodity leakages; and lack of effective nutrition education that require urgent attention.

Echoing similar thoughts, World Food Programme (WFP) Director Jon Brause said the book’s analysis showed there is no simple answer to the debate on cash transfers vs. food transfers. “We aren’t talking about something that is perfect, but we are talking about something that has to function in a system—those systems are political systems, economic systems and social systems. There are different drivers and different demands placed on the program by each of them,” Brause said. WFP’s programs may not be perfect, but they are effective, said Brause, adding that the international community should find ways to move more people out of food assistance programs.

In certain instances, cash transfers may backfire, said Louise Fox, chief economist, United States Agency for International Development. To better understand the impact of cash transfers on beneficiaries, she said, USAID recently started working on an impact evaluation with the non-profit Give Directly, which provides “no strings attached” cash assistance to poor households.

World Bank Senior Director (Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice) Michal Rutkowski said the book is the first step towards creating a forum where food and agriculture practitioners can share ideas. One long-term ideal, he said, is a social protection program that can withstand all shocks, such as a cash-based Universal Basic Income program.

In response to an audience member’s question on graduation from the social protection programs, Alderman pointed to the U.S. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, also known as food stamps), which works as a short term flexible safety net from which people graduate and can still fall back during times of need.

“It’s a question of 7 billion, and not 1.5 billion,” said IFPRI Director General Shenggen Fan in his closing remarks. “Because if 1.5 billion are not protected, they could become destabilized and it would affect the rest of the world.” A combination of food, voucher and cash assistance typically works best, he added. And, Fan said, agricultural subsidies should be reformed to free up monies to scale up social protection programs with strong linkages to nutrition and graduation.

Smita Aggarwal is an IFPRI Communications Specialist.