The following story by Jacopo Bordignon shares highlights from Chapter 7 of the 2014-2015 Global Food Policy Report, which was authored by Clemens Breisinger, Olivier Ecker, and Jean Francois Trinh Tan from IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division.

The world has seen more and more conflicts in recent years, such as in Syria, Nigeria, and Yemen. What explains these conflicts and what are the root causes and effects of ongoing civil violence?

The authors of a chapter on conflict and food security in the 2014-2015 Global Food Policy Report argue that, in addition to well-known triggers of conflict such as soaring food prices, natural disasters aggravate existing civil conflicts or may contribute to fueling new conflicts. They do this in several ways. Natural disasters can intensify social tensions by undermining access to water and agricultural land, by deepening inequalities between groups, and by raising food prices. Governments can further exacerbate these grievances either by providing inadequate responses to disasters or by distributing aid resources inequitably.

Figure 1 shows that violent civil conflict events in Africa were more frequent in countries that were harder hit by climate and weather-related disasters. The total number of people affected by such disasters in 2000–2013 is associated with the total number of violent civil conflict events −and the number of fatalities− in these events. Countries that are particularly vulnerable to both climate and weather-related disasters and violent civil conflicts include much of the Greater Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and the Sudan), Mali, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe.

Examples of conflicts that were likely fueled by drought include Sudan and South Sudan,Somalia, as well as the ongoing war in Syria. In particular, the Syrian civil war broke out after the country faced devastating droughts between 2006 and 2010. In total, 2 to 3 million people were affected by the droughts, 800,000 of whom became vulnerable to extreme poverty. Alongside a list of longstanding political, social, and economic grievances, the government’s failure to adequately respond to the 2006–2010 droughts was one of the factors that likely triggered the protests in March 2011.

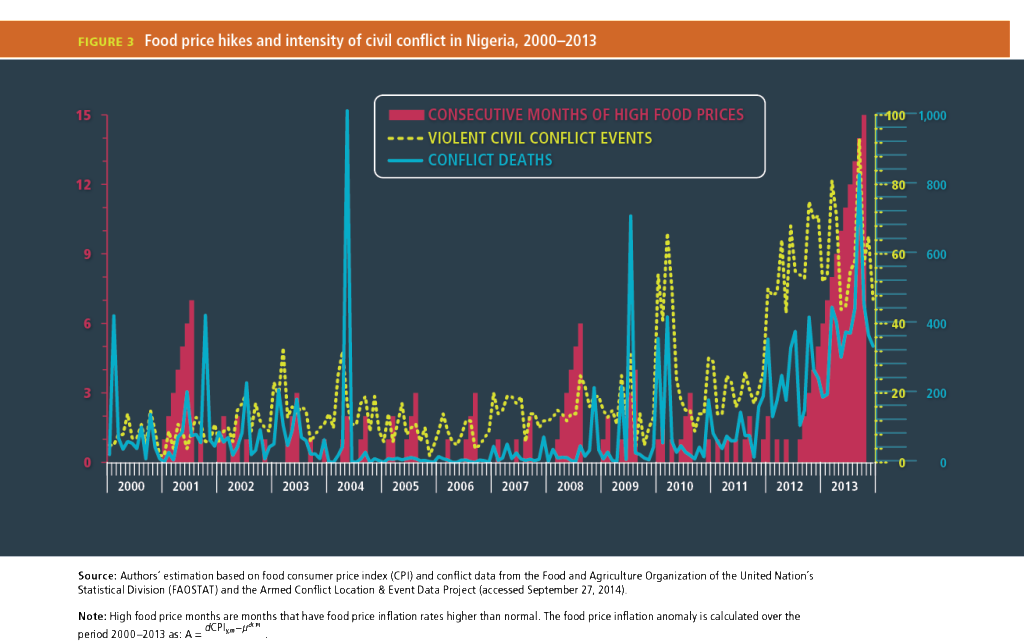

Food price shocks are both a determinant and effect of conflict. The recent escalation of violence in the northeast of Nigeria shows that violence contributes to soaring food prices and, as a consequence, food and nutrition insecurity. Food prices in the affected conflict areas increased because of both limited market activity and reduced trade flows. In fact there has historically been a close relationship between food price hikes and the intensity of civil conflict in Nigeria (Figure 3). The number of consecutive months with unusually high food prices from 2000 to 2013 is associated with both the number of violent civil conflict events as well as the number of deaths in these events.

To tackle natural disasters and food price shocks, governments should promote inclusive policies that build resilience to shocks and well-targeted and effective responses following these shocks. For example, effective social safety nets that can be scaled up in times of crises, such as the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) in Ethiopia or the Hunger Safety Net Programme (HSNP) in Kenya, can help to protect the poor against food price shocks. Examples from India, Kenya, and Zambia show that, if managed well, public grain reserves can help safeguard against global food price shocks, especially for countries that are heavily dependent on food imports. In the longer run, governments should support a competitive agricultural sector and trade integration.

It is important to provide adequate information to both policymakers and stakeholders, such as local farmers, on the likely consequences of government interventions and required resources to make these successful. Understanding government capacity for creating subsidies can help policymakers and development practitioners tailor programs for building resilience to rising food prices.