When women control the family finances, does it equate to a broader sphere of influence in household decisions? Research has suggested that women’s empowerment, both inside and outside the home, is closely correlated to women’s ownership of assets. A group of IFPRI researchers looked at this issue in depth with a conditional cash transfer (CCT) program in Brazil, Bolsa Família.

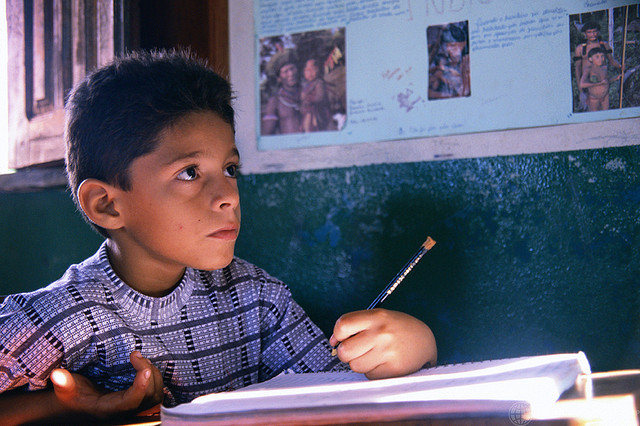

Implemented by Brazil’s Ministry of Social Development and the Fight against Hunger (MDS), Bolsa Família is the world’s largest CCT program, providing financial assistance to more than 12 million impoverished families throughout the country. As is increasingly the case in many Latin American CCT programs, the woman receives the family’s monthly benefits, conditional upon pregnant women receiving prenatal care, children receiving vaccinations and medical care, and children between 6 and 15 years of age attending school.

In a recent article in the journal World Development, “The Impact of Bolsa Família on Women’s Decision-Making Power,” IFPRI researchers Alan de Brauw , Daniel Gilligan, John Hoddinott, and Shalini Roy examine whether or not women’s control of resources stemming from this CCT program resulted in increased decision-making power in their households and, ultimately, better outcomes for children.

Over the course of two surveys, interviewing more than 15,000 households in 2005 and 11,000 of the same households in a 2009 follow up, researchers focused on a set of questions to gauge women’s levels of empowerment in the household. The female head of household or the female spouse of the head of household was asked who in the household generally made the decisions in eight categories: food purchases, clothes for self, clothes for children, children’s school attendance, children’s health expenses, durable goods, own labor supply, and contraception. When possible, women were asked these questions unaccompanied by their spouse (and if they were interviewed with the spouse present, the survey noted as much). It is also important to note that the “measures of women’s decision-making power refer to a woman’s subjective assessment of her own decision-making role” in these eight categories.

The authors discovered that the program did, in fact, empower women in many households; however the results were not uniform across the rural-urban divide.

In urban areas, women’s perception of their decision-making power saw “significant increases” between the two surveys in many capacities, including children’s school attendance (with an increase ranging from 12 to 15 percent), children’s health expenses (a 13 to 15 percent increase), and durable goods (an increase of 8 to 14 percent). The incidence of contraception-related decision-making was particularly interesting: participation in Bolsa Família increased women’s decision-making role over whether to use contraception by an astounding range of 16 to 18 percent.

In rural areas, however, the research painted quite a different picture. For these households, participation in Bolsa Família resulted in “no significant increases and possibly even reductions in women’s decision-making power.” One reason is that many rural women participating in the program are not bringing in additional income from work outside the home. In rural areas, Bolsa Família was linked to substantial decreases in women’s labor supply, possibly a consequence of the time commitment required to meet the program’s conditions. “If reduction in women’s labor supply in rural areas leads to reduction in women’s income and control of resources, the program may not improve decision-making power among rural women,” noted the study.

However, the program is not entirely a wash for these rural women, the study also found that “Bolsa Família may still improve their social status in the household in another dimension: feeling more respected by other household members.” The bottom line remains, though, that urban women enjoy the greatest benefits from the program and more work is needed to determine how to best reach women residing outside of cities and the conveniences they provide—such as proximity to schools and health clinics.

All in all, despite these regional differences in impact, the research suggests that Bolsa Família, and conditional cash transfer programs like it, could provide a pathway to empowerment, particularly for women in urban areas, improving both the welfare and equity of women, and the children in their care.