American agriculture has been among the foremost beneficiaries of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Under the agreement, agricultural trade between the United States, Canada, and Mexico has expanded immensely, rising from $16.7 billion in 1993 to $82 billion in 2013, an increase of 233 percent accounting for inflation. With this new trade came reduced costs for intermediate producers and consumers, and improved efficiencies throughout the North American agricultural sector, enhancing the region’s overall global competitiveness.

Elimination of tariffs and trade restrictions for most agricultural products has fostered a far more integrated North American market for grains, oilseeds, and livestock products. Feeder cattle from Mexico and pigs born in Canada are often fed and slaughtered in the U.S., with some processed meat products being exported back to those countries and elsewhere. It is not surprising that NAFTA garners high support among U.S., Canadian, and Mexico farm producers.

NAFTA is now being renegotiated at the behest of the Trump administration. In recent talks with his Mexican counterparts, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue echoed the producers’ sentiment for any new agreement: “Our goal is, first of all, to do no harm in agriculture.”

Of course, not everyone benefits from more open markets and not everyone is happy with NAFTA. Farms and firms that cannot supply markets as efficiently as their competitors across the border and have not adapted are prone to object, just as they objected when NAFTA was introduced more than two decades ago. Some fruit and vegetable producers in the American Southeast blame NAFTA for increased fruit and vegetable imports, which they say have reduced their market shares and prices. Now, they are looking to U.S. negotiators for redress.

To address those concerns, lobbyists for Southeast fruit and vegetable growers have supported new provisions that would make it easier for growers to bring anti-dumping cases based solely on data from a single marketing season. Current trade law and practice typically requires antidumping measures to show injury to a majority of producers based on an analysis of three years of annual data. These arguments seem to have caught the attention of the Trump administration, which has included language on the need for new trade remedies for perishable and seasonal products among its NAFTA renegotiation objectives.

It is true that U.S. fresh fruit and vegetable imports have soared under NAFTA. Imports from Mexico have grown from $1.5 billion in 1995 to over $10 billion in 2016 (figure 1). Some of those products, like papayas and pineapples, are more tropical in nature and see little competition in the U.S. Other imported fruits and vegetables are shipped counter-seasonally and do not compete directly with U.S. production, the bulk of which occurs during the summer months (figure 2).

Even for Florida, where the harvest season overlaps with Mexico’s for some products, there is often only indirect competition. For example, Florida’s winter tomato crop is largely shipped to markets in the East, while the bulk of Mexico’s crop goes to western states. Nonetheless, in 1996 declining production and market share led the Florida tomato industry to file an antidumping petition against Mexico. The U.S. and Mexican governments compromised on the dispute; the dumping investigation was suspended, while Mexican tomato growers agreed to set minimum prices for their U.S.-bound exports. The so-called “suspension agreement” has remained in place for two decades, but the Florida tomato industry is not satisfied, and now seeks changes in NAFTA to make antidumping investigations for fresh and perishable products easier to pursue.

Even while recognizing the loss of market share due to NAFTA imports, it would be a mistake for the U.S. to pursue the changes advocated by the Southeastern fruit and vegetable industries. First, in any negotiations, concessions do not come without some quid pro quo, and Mexico has been clear that it has no interest in agreeing to provisions that would curtail its exports. So, Mexico could demand a high price such as restrictions on major agricultural imports from the U.S.

Second, any changes to antidumping provisions for fresh and perishable crops could be easily used against U.S. producers of similar products by Canada or Mexico. These U.S. exports to NAFTA partners totaled over $4 billion in 2016. The proposed provisions would allow, for example, hothouse lettuce producers in British Columbia or apple producers in northern Mexico to seek protection for their industries as well, clamping down on their American competitors. Stronger antidumping rules may benefit weak U.S. industries that cannot compete in open markets, but at the expense of strong ones that can. As a matter of policy, investing in the losers is never helpful for creating economic productivity and prosperity.

The ultimate losers of such a policy would be workers and consumers. Changing diets and growing off-season supplies of fresh produce from outside the U.S. have fostered a shift in American consumption away from processed fruits and vegetables and toward fresh produce.

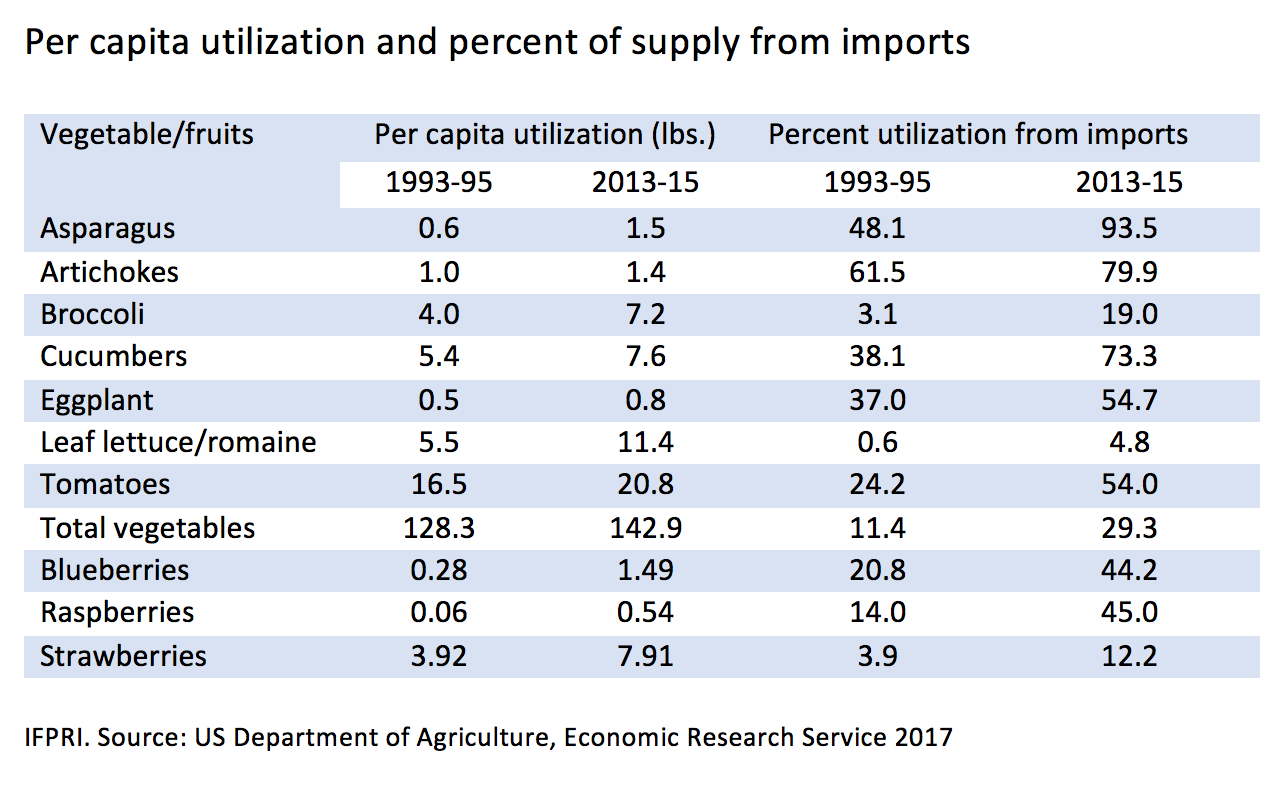

Table 1 shows the changes in per capita utilization of selected vegetables and berries in the U.S. since the implementation of NAFTA. Total per capita consumption of vegetables increased 11 percent over the last 20 years, from 128.3 pounds per person to 142.9 per person. That includes increases in the per capita utilization of so-called powerhouse fruits and vegetables—items high in nutritional value such as greens, broccoli, and peppers, as well as fruits such as berries, associated with reduced risks for cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

In short, imports have been a big factor in increased consumption of fruit and vegetables.

Of course, there is much room for improvement in NAFTA. The treaty was drafted a quarter century ago, and much has changed in global commerce since then. Global supply chains have developed further, diets have changed, and e-commerce has emerged as a force in world markets. But changes to NAFTA should be focused on achieving more open markets—not more government control. Tariffs remain on a handful of protected product categories (dairy, sugar, and poultry for example) and despite progress, there are opportunities to further lower regulatory costs that impede trade. The NAFTA renegotiations provide an opportunity to address those shortcomings.

NAFTA has been beneficial to U.S., Canadian and Mexican farms and agricultural firms—and that is positive for farmers and workers. But if the mantra is to “do no harm” in the negotiations, it is critical to remember that consumers and the costs they would bear count as well. Consumers have been prime beneficiaries of trade liberalization. They should not be sacrificed at the altar of protectionism.

Joseph Glauber is a Senior Research Fellow in IFPRI’s Markets, Trade and Institutions Division and a former U.S. Department of Agriculture Chief Economist.