Global food prices are on the rise. FAO’s Food Price Index indicates prices in international markets have risen by 40% from a year ago (May 2020). Prices of vegetable oils in particular have surged, showing an increase by almost 110% over the past year. Other commodity prices, like those for metals, oil, and other minerals prices have also shown sustained increases since mid-2020.

How concerned should we be? First, it is important to realize that the drastic year-on-year change in food prices reflects in part a “base effect,” i.e., a rebound from the 10-year low seen in May 2020, a few months into COVID-19 restrictive measures. Second, international food prices have not reached historical heights (Figure 1), although they have risen close to the levels reached during the food price spikes of 2007-2008 and 2011-2012. While food prices are high, for now there is no reason for panic.

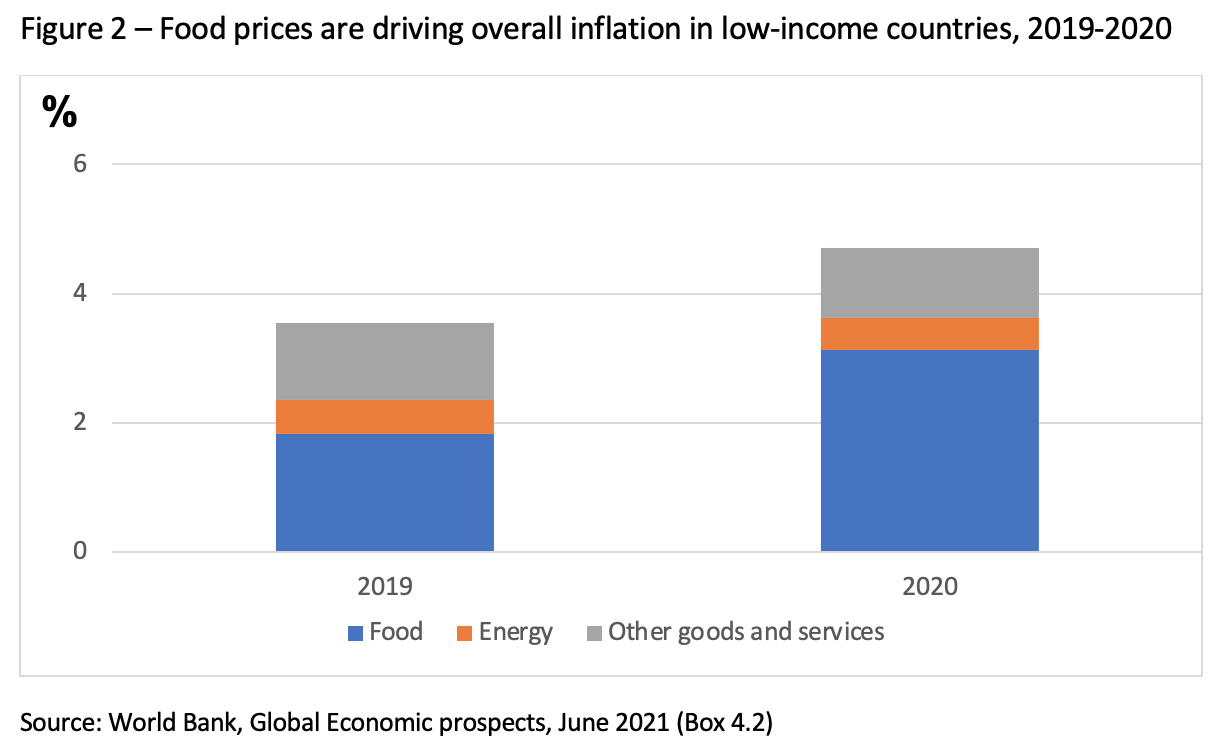

A bigger concern is the sharp rise in domestic food prices in many countries, especially low-income countries, over the past year. According to the recent World Bank report Global Economic Prospects (June 2021) rising food prices have been the main driver of overall inflation, which was already high in those countries prior to the pandemic (Figure 2).

Several factors are at play in the recent global surge in food prices.

On the supply side, production has been hampered by poor weather in some major producing regions. Brazil is currently facing the worst drought conditions in almost a century, raising serious concerns about both maize and sugar harvests. Similarly, Southeast Asia has seen slower than expected growth in vegetable oil production. Concerns over supply lessened following new U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates released in May showing better production forecasts for northern hemisphere crops. Nonetheless, global markets for major staple foods remain tight. Stock-to-use ratios for maize and soybeans are below normal levels (Chinese stocks not included). In tight markets, price hikes and price volatility are easily triggered.

Markets have also tightened because of stronger-than-usual demand for animal feed and industrial use. China has been a major driver. With the recovery of its economy and the recovery of the livestock sector from African swine fever, China’s demand for wheat, maize and other feed grains, and soybeans has risen significantly to meet rising feed demand. International prices for vegetable oils are also set to increase further, as demand for biodiesel will expand as countries reopen and their economies recover, especially in those countries with fixed mandates for biodiesel use. The poor will be heavily impacted as vegetable oils are important to their diets.

A weaker U.S. dollar is another factor driving up world market prices. The dollar depreciated between 10% and 15% against other major currencies over the past year. Since most of commodity trade is in U.S. dollars, a weaker greenback typically pushes prices up as traders demand a higher price to compensate for the exchange loss. The weaker dollar is currently playing into both stronger trade and rising prices.

Low-income countries are most affected by the rise in international food prices. In these countries, food accounts for about half of consumption baskets and 20% of imports. Rising agricultural commodity prices in world markets therefore tend to have a significant impact on domestic food price inflation in these countries. Low-income countries have also been hit hard by the global recession during 2020, driving down the demand for their exports and, lacking access to sufficient contingency finance, causing their exchange rates to depreciate. This further pushed up the cost of imported food.

While there are some concerning trends, there is no reason for panic over a possible repeat of the global food price crisis of a decade ago. Production prospects for staple crops look favorable for the 2021-2022 season. Yet, markets for staple crops may remain tight in the near term with rising demand from China and expected production shortfalls in Brazil and other Latin American producing countries. As emphasized in the latest AMIS Market Monitor, these trends outweigh production growth, reduce global grain inventories, and put further upward pressure on international food prices. This could spell more trouble for poor populations, particularly in Africa South of the Sahara and South Asia, who exhausted their savings during the COVID-19 pandemic and who may not yet be seeing much recovery of livelihoods. Rising inflation, particularly when driven by sharp increases in food prices, raises poverty, increases malnutrition, and curtails the consumption of essential services such as education and health care. To cushion the worst of those impact, further strengthening and coverage of social protection systems will be critical.

Sara Gustafson is a freelance writer; Joseph Glauber, Manuel Hernández, and David Laborde are Senior Research Fellows with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division (MTID); Brendan Rice is an MTID Research Analyst; Rob Vos is Director of MTID.

This post also appears on the Food Security Portal blog.