The International Day of Rural Women (Oct. 15) was established more than a decade ago to recognize the central role of women in improving rural development and food security. It was placed directly before World Food Day (Oct. 16) to highlight women’s key roles in agricultural production, in food processing and marketing, as well as in the preparation of healthy, nutritious and sustainable meals for their families.

Rural women are facing a number of pressing challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the intensifying impacts of climate change, that hinder their economic empowerment and efforts to achieve gender equality—goals inextricably linked to women’s ability to “Cultivate Good Food for All,” this year’s IDRW motto. The World Economic Forum (2021) estimates that the time needed to close the global gender gap increased from 99.5 years to 135.6 years due to the pandemic. Food insecurity has also dramatically increased in many parts of the world as a result of COVID-19.

According to the 2021 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report, 2020 saw as many as 161 million more hungry people than 2019, while nearly 2.37 billion people did not have access to adequate food—an increase of 320 million people over the prior year. IFPRI phone surveys of rural areas in Africa south of the Sahara and Asia conducted throughout the pandemic period found that more than half of all respondents in six of seven countries worried that they would not have enough food to eat as a result of the pandemic and that in most cases, women worried more about food insecurity than men.

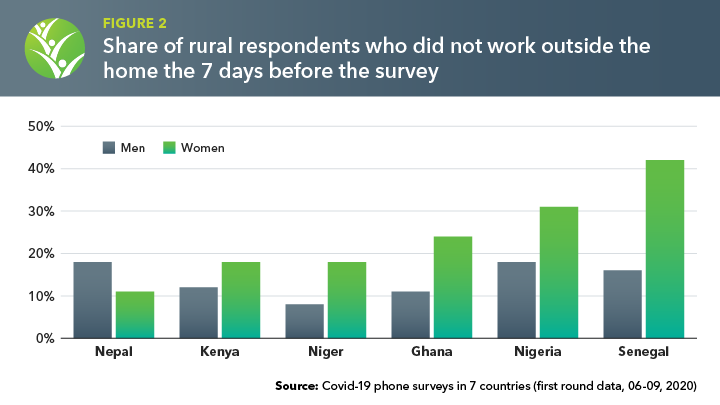

More rural women than men reported they were not working outside the home in six of seven countries following the onset of the pandemic (Figure 2). This might reflect social norms and traditions, but even when outside work opportunities resumed following lockdowns, women reported working fewer hours than they did pre-pandemic. This may be linked to loss of job opportunities—women are more likely to work in the informal sector, including as agricultural laborers or food vendors. But it is also likely due to their increased responsibilities at home linked to school closures or sickness of family members, as well as the increased competition for jobs with (largely male) migrants returning from urban areas where overall job losses were even higher. Thus the pandemic had a significant impact on women’s income, leading to a decline in assets and savings and an increase in indebtedness. These setbacks will have broad impacts—in particular, making it harder for women to respond to climate-driven shocks such as extreme weather events.

Even if more women were able to work in agriculture and other food system jobs, their productivity suffered during the pandemic due to a lack of access to digital extension services—often the only information available—compared to men. This is another harbinger of the growing challenges they face from climate change; effective responses to the climate crisis require timely and actionable information. A recent study of COVID-19 impacts on women’s access to extension services in Nepal’s Dang province and India’s Gujarat state found an increased reliance on social networks after lockdowns and reduced dependence on formal sources of information—which was already low before lockdown. This directly reduced women’s agricultural productivity in Gujarat, while farmers in Dang reported concerns about input availability and pest attacks.

Addressing these structural inequalities is critical to global pandemic recovery and to tackle the ongoing challenges of climate change. That means reducing women’s time burden, removing social and other barriers to women’s mobility, access to information and economic inclusion, which also helps to ensure that all people have access to sustainable, healthy diets.

The new 50/50 initiative highlights inequalities in who benefits from the global food system and monitors progress towards closing gender gaps. Similarly, more and more organizations are committed to strengthening women’s empowerment as reflected in the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) Draft Voluntary Guidelines on Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Empowerment in the Context of Food Security and Nutrition. While women’s empowerment is not synonymous with eliminating COVID-19 impacts or climate resilience, many synergies exist. Many of the same indicators of women’s empowerment—including the freedom to make choices that meet their needs, control over income and assets, and access to and control over resources, like land—are important factors that support greater resilience to shocks and stresses.

While long-term resilience-building programs and interventions are being developed, immediate interventions are needed to address the acute income shocks and food insecurity challenges now affecting rural women and their families.

These include food banks, expanded school feeding programs, and other interventions that can effectively target poorer rural households and at the same time reduce the large increase in inequity in access to nutritious food and other resources. Credit support programs with highly favorable rates focusing on poor rural women should be established to counteract potential long-term indebtedness and help ensure that children can return to school rather than work to support their families. In areas where domestic water access remains extremely limited—including many countries in the Sahel region—rural water access should be improved to fight the pandemic and to provide sufficient water for drinking and food preparation.

Medium-to-long term efforts should focus on expanding women’s access to digital technologies, including mobile phones and the internet. Asset-building programs targeting women are also essential—particularly in places where women have recently lost income and have drawn down assets. Over time, the right combination of efforts and interventions can help not only to overcome current obstacles, but to foster greater resilience and empowerment for rural women, so that they can truly cultivate good food for all.

Claudia Ringler is Deputy Director of IFPRI’s Environment and Production Technology Division (EPTD), and Deputy Director of the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land, and Ecosystems (WLE); Elizabeth Bryan is an EPTD Senior Scientist.