Translation option:

Violence against women and girls (VAWG) is a persistent global problem. Physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence alone affects over one in four women, while rates of violence against girls often surpass 50% in the home, at school and in public settings. Developing effective policies to reduce violence depends on having accurate data. Yet household surveys, a principal source of data on VAWG, often underrepresent the extent of the problem. Survey participants may be reluctant to disclose their experiences with violence due to shame, stigmatization, fear of consequences, and other barriers. While the importance of these factors tends to vary by target population and context, improving the quality of such data can help both drive investments and attention to addressing VAWG, and contribute to critical decisions of what works for prevention and response.

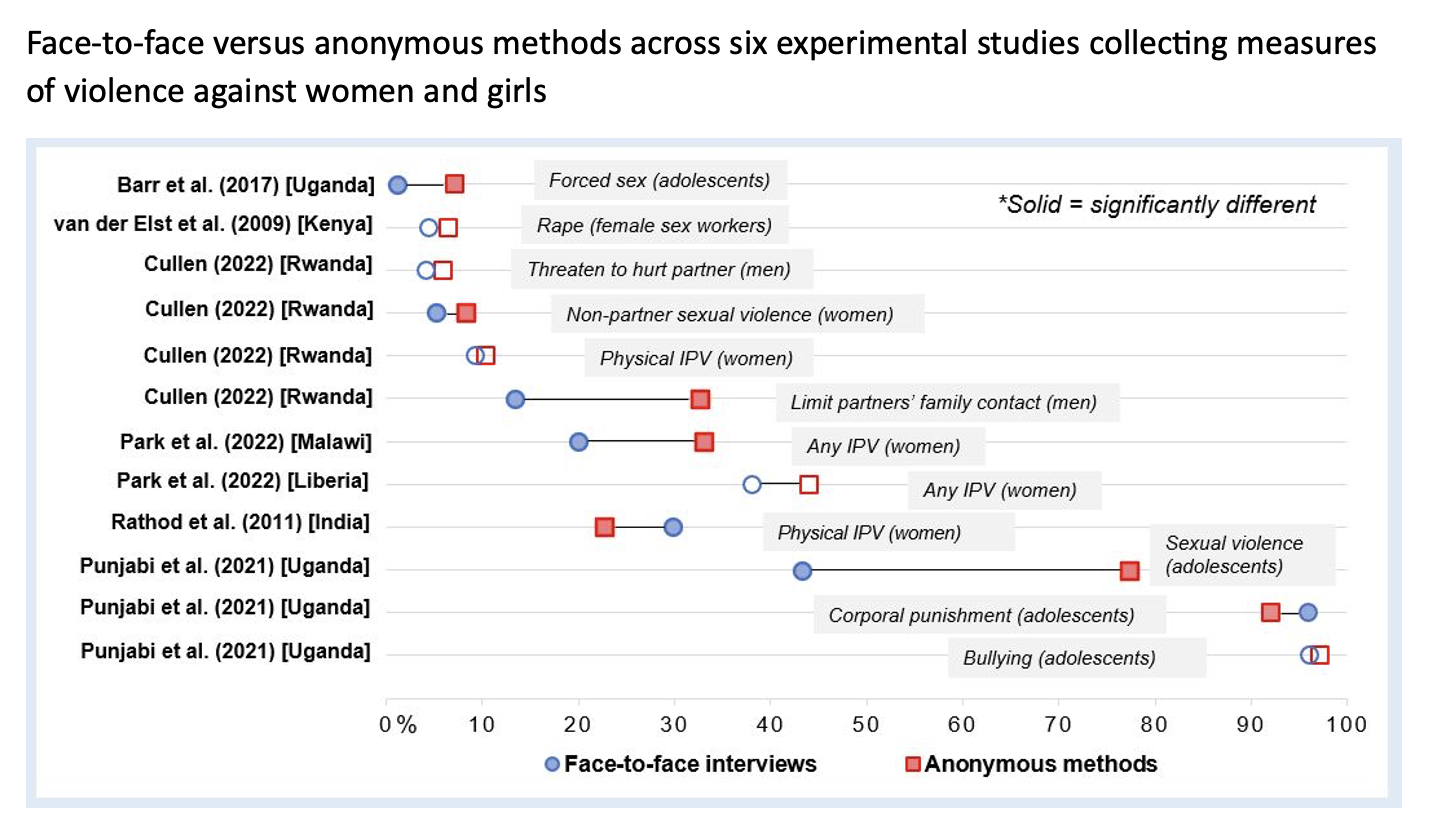

Researchers have experimented with methods to increase accuracy and quality of data, including using anonymous survey methods—such as audio-computer assisted self-interviews (ACASI)—that facilitate participant privacy. Previous studies from a variety of settings comparing traditional face-to-face methods with anonymous methods show promise; for example, across six existing experimental studies in India, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Rwanda, and Uganda, approximately half of the violence outcomes measured were significantly higher using anonymous methods compared to face-to-face (Figure 1). Yet the mixed results across settings and types of violence raise questions as to how well anonymous methods work in diverse settings, populations and measures.

In a recent IFPRI discussion paper, we outline a randomized experiment in Senegal comparing two methods of survey data collection on VAWG, showing that an anonymous approach yielded consistently higher reported levels of violence across a diverse set of VAWG indicators, as compared to in-person interviews.

Figure 1

Notes: IPV = intimate partner violence; studies include: Barr et al. 2017, Cullen et al. 2022, Park et al. 2022, Punjabi et al. 2021, Rathod et al. 2011, van der Elst et al. 2009.

Experimenting with survey administration in Senegal

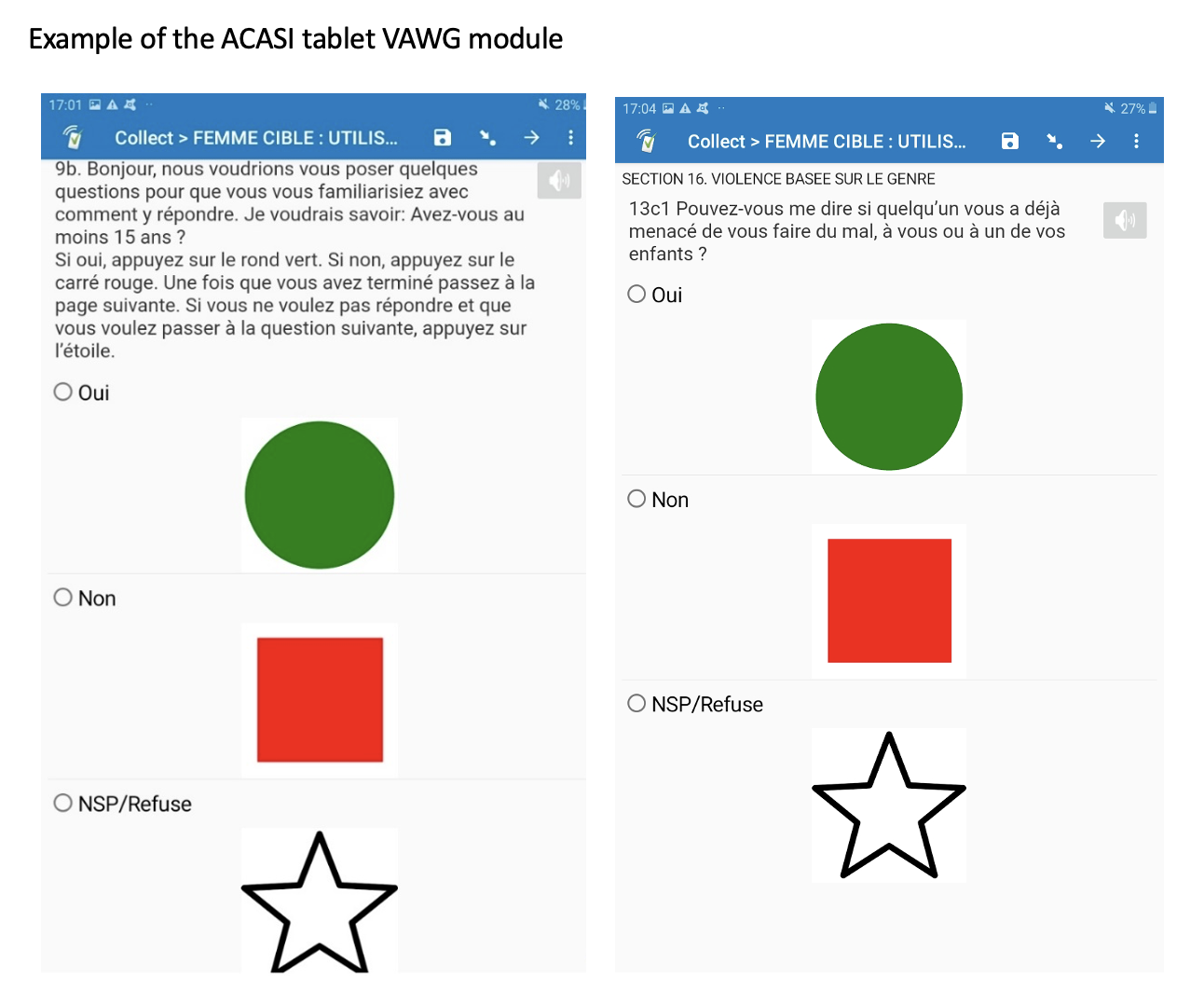

As part of a large-scale survey of approximately 3,400 women and girls (aged 15 to 35) in the rural Kaolack and Kolda regions of Senegal, we randomly assigned participants to either be asked VAWG questions by female interviewers who underwent training to facilitate respectful and empathetic solicitation of VAWG, or to complete audio-computer assisted self-interviews (ACASI). In the ACASI group, participants listened to questions on headsets and keyed in answers using colored shapes on tablets (Figure 2, green circle = yes, red square = no). To prepare participants, interviewers walked them through the self-interview process, including test questions. If participants indicated they were not comfortable completing the module, or demonstrated they did not understand how to manipulate the tablet, they were reassigned to be interviewed in person.

In both groups, women and girls in current or recent partnerships were asked standard question modules on intimate partner violence (IPV) following the Senegalese Demographic and Health Survey (15 questions on specific acts corresponding to emotional, physical and sexual IPV). In addition, all women and girls were asked a set of questions regarding violence perpetrated by anyone in the household or community (18 questions on specific acts corresponding to emotional, physical and sexual harassment and violence). We analyzed data by comparing prevalence measures for the group randomized to face-to-face interviewers to the group randomized to ACASI, controlling for a number of background characteristics and interviewer fixed effects.

Figure 2

Notes: Left screen shows an example of a test or training question (audio via headphones were translated into Wolof or Pular scripts, the dominant languages in each region), while the right screen shows an example of an emotional IPV question.

Women and girls had higher disclosure with self-administered surveys

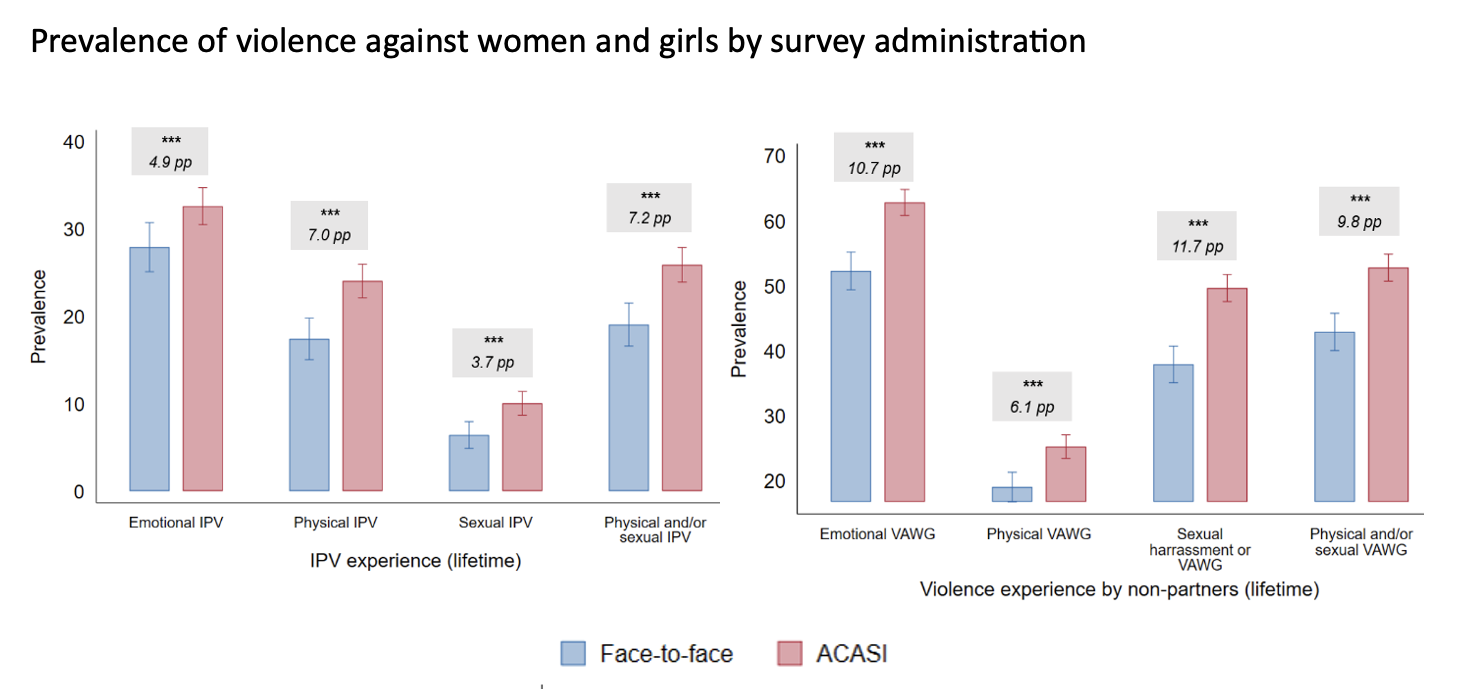

Results shown in Figure 3 indicate that the prevalence of reported lifetime violence is higher in the ACASI group (pink bars) as compared to the face-to-face group for all outcomes (blue bars). Increases range from 4-7 percentage points (pp) for prevalence of IPV and from 6-12 pp for prevalence of non-partner VAWG. For combined measures of any physical and/or sexual violence, these differences equate to a 39% increase in prevalence for IPV and a 23% increase in prevalence for non-partner VAWG among participants using ACASI.

In general, disclosure is higher for less common types of violence (including sexual IPV), which supports the hypothesis that stigma and shame contribute to low disclosure in this setting. These same trends hold for measures with a shorter (past year) recall period, indices of VAWG frequency and axillary measures of reported willingness to intervene in the case of physical IPV experienced by a neighbor, and willingness to seek help.

Figure 3

Notes: IPV = intimate partner violence; VAWG = violence against women and girls; 90% Confidence intervals shown, standard errors are clustered at the village level.

Why does this matter—and what do we need to know next?

We show that using self-administered surveys to collect VAWG data results in higher disclosure rates among a population of adolescent girls and young women in rural Senegal. This suggests that similar surveys in Senegal using interviewer-administered surveys could be severely underestimating VAWG prevalence. In fact, our study finds rates of lifetime physical and/or sexual IPV that are double the prevalence rates found in the most recent nationally-representative Demographic and Health Survey data (at 13%). This is not overly surprising, as norms in Senegal support the view that IPV should be viewed as a family matter—as demonstrated by qualitative data collected in tandem with this study:

“As is the case for all couples, there may be problems—but, as they say: ‘dirty laundry is washed at home’—so their intimate problems, they can settle internally. They won’t need to tell me.” —Community Health Volunteer, Kolda

Moreover, there are few services or formal recourse available to women to address VAWG, and Senegalese legal code still does not recognize some forms of violence, including marital rape, or other forms of sexual or emotional IPV. To promote progress in effectively addressing VAWG, one crucial step is to generate more accurate data on the prevalence and nature of such violence to help drive investment and attention at the national level.

There is also a lot more we need to learn about how to accurately and ethically collect measures of violence, for example:

- Understand which factors contribute to underreporting: We know little about which characteristics lead to underreporting across different data collection methods. In our study, we assessed how variations in attitudes and norms related to VAWG, as well as other survey logistical factors contributed to increased disclosure—finding few correlates. A better understanding of why underreporting occurs is essential to see how our results might apply in other settings and to suggest when ACASI may be a useful modality to reduce biases.

- Learn more about costs and trade-offs of using ACASI models: Despite their potential benefits, approaches such as ACASI require investment in module development and piloting to ensure recordings and administration run smoothly. There are also cost trade-offs. For example, self-administered modules take longer in the field; in our case there was an 8% longer total questionnaire time-to-completion. Finally, self-administered surveys are not appropriate in low literacy populations for complex questions that go beyond “yes” and “no” answers (e.g., “who was the perpetrator?”). Previous research in low-literacy populations in Ethiopia and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) show ACASI was easily understood by participants—however, more recent research from Liberia and Malawi suggests some women may not understand ACASI—resulting in misreporting. Thus logistics around implementation and the suitability of ACASI in different populations should also be scrutinized.

- Invest in unpacking women’s experience with interview methods and the ethical implications of survey administration: Ultimately, we want to give participants the best possible experience with data collection to avoid re-traumatization and promote a “do no harm” approach. Questions also remain about which ethics protocols are essential to put in place and to report in self-administered surveys, and how the lack of contact with a potentially empathetic interviewer may change women and girls’ experience with data collection.

Continued ethical experimentation with data collection that allows women and girls to better represent their experiences with violence can lead to more accurate representation of the problem—and better inform which policies and programs hold the most promise to end VAWG.

Amber Peterman is a Research Associate Professor at the University of North Carolina; Melissa Hidrobo is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Poverty, Gender, and Inclusion Unit; Malick Dione is a Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Nutrition, Diets, and Health Unit. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed.

Referenced discussion paper:

Peterman, Amber; Dione, Malick; Le Port, Agnès; Briaux, Justine; Lamesse, Fatma; and Hidrobo, Melissa. 2023. Disclosure of violence against women and girls in Senegal. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2195. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.136775

We thank members of the study team contributing to the overall evaluation and previous survey waves, including Abdou Salam Fall, Jessica Heckert, Moustapha Seye and Annick Nganya Tchamwa and IFPRI colleagues Nicole Rosenvaigue and Rock Zagre for excellent grant administration and assistance with survey coding. We thank the interviewers and field team from ASSMOR who managed the data collection process, as well as the women and adolescent girls interviewed for this study. We thank the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM), the CGIAR Gender Platform and an anonymous donor for funding this work.