Though fish has long been the largest source of protein in Bangladeshi diets, for decades persistent high prices made it difficult for most to acquire. In the early 1990s, per capita annual fish consumption was a low 10 kilograms. In 2005, the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) suggested that even reaching a per capita annual consumption of 18 kg would be a remarkable improvement. But only five years later, national survey estimates put the annual per capita consumption of fish in Bangladesh at 23 kg.

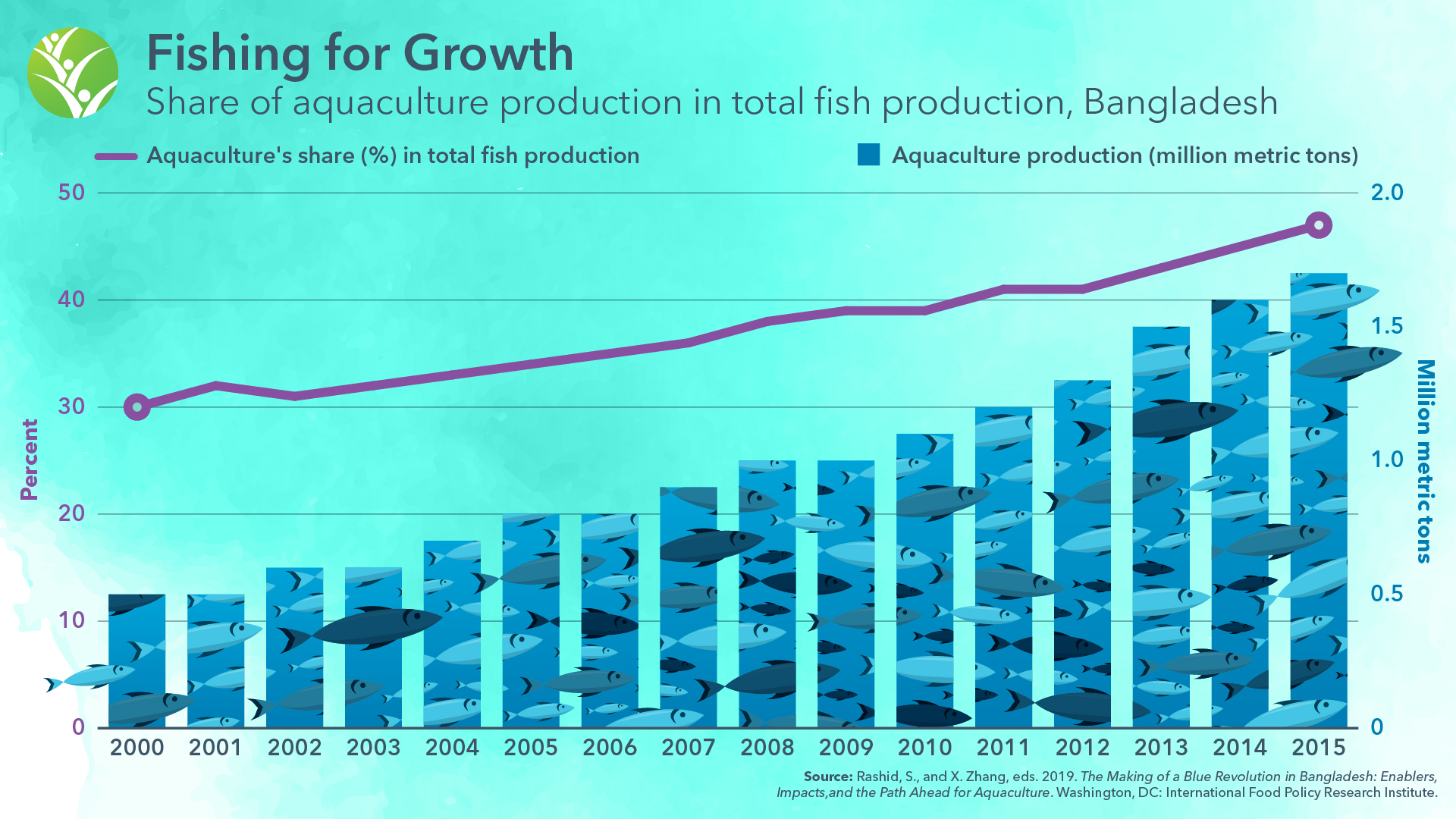

It was the exponential growth in Bangladesh’s aquaculture industry that made the difference. This remarkable transformation is assessed and documented in the new IFPRI book The Making of a Blue Revolution in Bangladesh: Enablers, Impacts, and the Path Ahead for Aquaculture, edited by South Asia Director Shahidur Rashid and Senior Research Fellow Xiaobo Zhang. The book lays out the factors that led to this revolution, the implications for poverty and welfare, and the prospects for aquaculture going forward. It was launched at an event Oct. 27 in Dhaka.

Some of the enabling factors for the transformation, such as improving technology and infrastructure, are not unexpected. But the book reveals many nuances, including the intensification and specialization in fish production, and the clustering of various players working in aquaculture. There has also been significant growth across the entire fish value chain. The number of hatcheries, feed mills, feed dealers, and fish traders more than doubled during 2004-2014. The fish value chain survey also found that farmers have made greater use of hatchery seed, fish feed, chemical applications, and quasi-fixed capital.

Clustering has been a key dynamic in the industry’s growth. The numbers of fish traders and farmers have increased in concert with their growing physical proximity. The research also found that fish traders and feed dealers are increasingly acting as middlemen, with the traders connecting buyers to sellers, while the dealers bring feed to the production zones. This combination of proximity and diversity means easier access to markets, which in turn brings more modern inputs to the farmers and less difficulty in marketing and communication.

Early studies cautioned that a growth in aquaculture would not benefit the poor of Bangladesh since fish farming required land and most Bangladeshis are effectively landless. But research has since shown that the growth of aquaculture had had a large positive welfare effect across all income levels. Fish supply outpacing demand, along with lower transaction costs, lowered prices for all consumers, leading to greater fish consumption. The authors’ analysis shows that consumption increased across the gender, regional, and income spectrums, with poorer households having the most to gain from the change.

The growth in fish production has also significantly contributed to the nationwide reduction in poverty. Long-run welfare estimates indicate that aquaculture’s contribution to poverty reduction was 1.74% between 2000 and 2010. Poverty declined by 17.4 percentage points overall in that same time frame, meaning that aquaculture’s overall contribution to poverty reduction during that time period was around 10%.

Despite the explosive growth of the last 30 years, the book notes, the full potential of aquaculture has yet to be realized in Bangladesh. The nation’s aquaculture productivity is only 4.26 metric tons per hectare. If even half the pond area currently used were converted to intensive farming systems (which have yields of over 100 metric tons per hectare), production would increase more than twelve-fold.

For Bangladesh to reach this potential, its remaining production constraints must be addressed; then the country can move on to tap the export potential of surplus fish. This will be a unique challenge since most seafood export is controlled by corporate entities, while fish farming is composed of multiple small holdings. This means a redesign of fish export industry institutions and regulations should be considered, the authors write. In addition, the institutional capacity of the aquaculture market needs updating: A National Fisheries Policy was adopted only in 1988. While it contained many points relevant to fish farming, it had no separate section regarding aquaculture.

Bangladesh has two great endowments, water, and labor. Just as the availability of cheap labor fueled the expansion of the garments sector, the nation’s waters are now fueling a boom in fish production. The Making of a Blue Revolution provides insights needed to improve aquaculture policies in Bangladesh and move the industry into its next, still more promising, stage of growth.

Sulin Chowdhury is a Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division, based in Dhaka, Bangladesh.