Climate change is increasing the frequency of adverse weather events and reducing agricultural productivity, particularly in warmer regions of the world (Ortiz-Bobea et al 2021). Smallholder farming households in developing countries depend on agriculture for their livelihoods and spend a larger proportion of their income on food, making them the most vulnerable to harvest failures (Hallegatte et al 2020).

Households employ several strategies to prepare for potential income risks and to cope with the consequences of shocks. Yet these ex-ante and ex-post approaches both have downsides. Ex-ante risk management strategies such as reducing or forgoing investments can prevent the accumulation of productive assets and trap already poor households in persistent poverty (Carter and Barrett 2006). Ex-post risk coping strategies such as increased borrowing or reduced consumption can have negative implications for welfare.

Gender plays a role in how farmers are exposed to and manage weather risks. Studies show that the consequences of risk are often not distributed equitably within a household, with women disproportionately bearing the negative impacts of weather-related shocks (Asfaw and Maggio 2018). To examine these issues further, we used quantitative and qualitative primary data from a multi-year experimental impact evaluation of an ICT-based crop insurance innovation in India, implemented between 2018 and 2023 (Ceballos, Kramer and Robles 2019). We investigate whether risk coping strategies are different across genders within farming households, and how to make insurance more effective for vulnerable groups such as women.

We find that women experience production shocks differently from men, and that women’s participation and risk exposure can vary substantially depending on whether their household cultivates cereal or horticultural crops. These findings underscore the need to design and deliver customized risk management tools such as crop insurance for groups most vulnerable to the negative effects of crop damage.

Context

The research was conducted in the state of Haryana. Located in the hot semi-arid trans-Gangetic plain of India, Haryana is one of the most agriculturally advanced regions in the country but continues to lag on indicators of women’s empowerment, including sex ratio and literacy among women. Over 90% of land cultivated in this region is irrigated and the vast majority of farmers cultivate rice and wheat (Govt. of Haryana 2022). In recent years, with rapid depletion of the water table and an increase in unseasonal rain, crops have been failing more frequently due to drought, excess temperature, lodging, and pests and disease (Yadav and Rai 2001).

Such risks, affecting production and prices, are major hurdles preventing farmers from transitioning from rice and wheat towards more nutritious and sustainable cropping systems (Basu 2024). Despite the availability of a subsidized national insurance program for several crops, very few farmers are insured against catastrophic weather-related crop damage, largely due to poor awareness and perception of crop insurance, as well as challenges in assessing losses accurately (Khan et al 2019; Kramer et al, 2022).

Main findings

Against this backdrop, we assessed risk profiles and coping strategies for men and women in tomato, wheat, and rice farming households across four districts of Haryana: Karnal, Kurukshetra, Yamunanagar, and Panipat. In partnership with the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA), we invited 1664 randomly sampled farmers cultivating less than 15 acres from 100 villages to participate in the study. The male and female heads of each household were each interviewed separately at baseline, prior to insurance program implementation. Below are the main findings from this research:

1. Women suffer consequences of agricultural production shocks differently than men.

While most women in the study region did not play an active role in agriculture, most were aware of production losses, and supported their households to cope with shocks. Adopted coping strategies differed vastly between men and women, with women often assuming primary responsibility for smoothing income and consumption (Figure 1). In a subset of 555 households where both male and female respondents reported crop losses, women were significantly more likely than men to borrow (mostly from informal sources of credit such as kins and community networks), reduce food and non-food expenditures, and seek additional work. Women were 55% more likely to borrow informally from kinship and community networks, 21% more likely to reduce expenditure on food or eat less, 57% more likely to reduce spending on non-food consumables such as clothes, and 24% more likely to seek additional work. Qualitative research revealed that men typically shared information on financial constraints with women and expected them to identify ways to manage household expenses including during income shocks (Misra et al., 2020).

Figure 1

2. Horticulture producers are more susceptible to negative consequences of production risk..

Damage due to extreme weather and related factors such as pests and diseases was more common in horticulture crops, with over half of farmers reporting crop losses in the last 12 months in the case of tomato, compared to less than 25% in the case of rice and wheat. Tomato growers farmed on smaller landholdings of 0.5-1 acre and 96% were tenant farmers or sharecroppers with little access to government subsidies and loans. Compared to women from rice and wheat-growing households, women from tomato-growing households were significantly less empowered1 (33%), were less likely to belong to women’s groups (2%), and were far more likely to report suffering from health problems (44%) and experience tension in the household (94%) after crop loss events. These findings are likely to be further exacerbated by price risk, also common in horticulture markets (Ceballos et al 2021).

3. If crop insurance is to be a solution, it needs to better serve women and a diverse range of crops.

Crop insurance can help farmers cope with losses without having to rely on informal borrowing. However, insurance programs are currently rarely designed to be gender-responsive or to be equally accessible for women and men; they are not easily available for horticulture crops; and they suffer from low take-up overall. In a separate study conducted with 100 households in 2017, we find that willingness-to-pay for insurance2 (including both commonly available weather-index based insurance and a novel indemnity insurance piloted by IFPRI) was significantly lower—about 20%— among women than among men. Key barriers reported by women included lack of access to information, low mobile ownership to use ICT-based methods such as mobile money, lack of trust in financial institutions, low ownership of land, and low decision-making power in agriculture.

Discussion

Our findings support a large body of research indicating that when uninsured, agricultural production shocks from climate change can have serious welfare consequences that often disproportionately impact women. Differences in access to resources, institutions, information, and decision-making power reduce the adaptive capacity of women (FAO 2011).

If crop insurance is to play a role in reducing the negative welfare impacts of crop damage, it must be redesigned in a manner to overcome these constraints and reach disadvantaged populations—including women and horticulture producers. Although traditional crop insurance is heavily restricted by regulation, governments and financial intermediaries can explore novel financial tools such as risk-contingent credit, state-contingent cash transfers to women or collective insurance of women’s groups, and leverage technology to improve the supply of affordable insurance for horticulture and nutrient-dense crops. Stronger evaluations of the performance and effectiveness of these solutions are areas for further research.

Samyuktha Kannan is a PhD Candidate in Development Economics at Wageningen University & Research, Netherlands; Berber Kramer is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Unit. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.

An earlier version of this blog post was published as a case study accompanying the report “How Does Climate Change Impact Women And Children Across Agroecological Zones In India: A Scoping Study” prepared by the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, 2024.

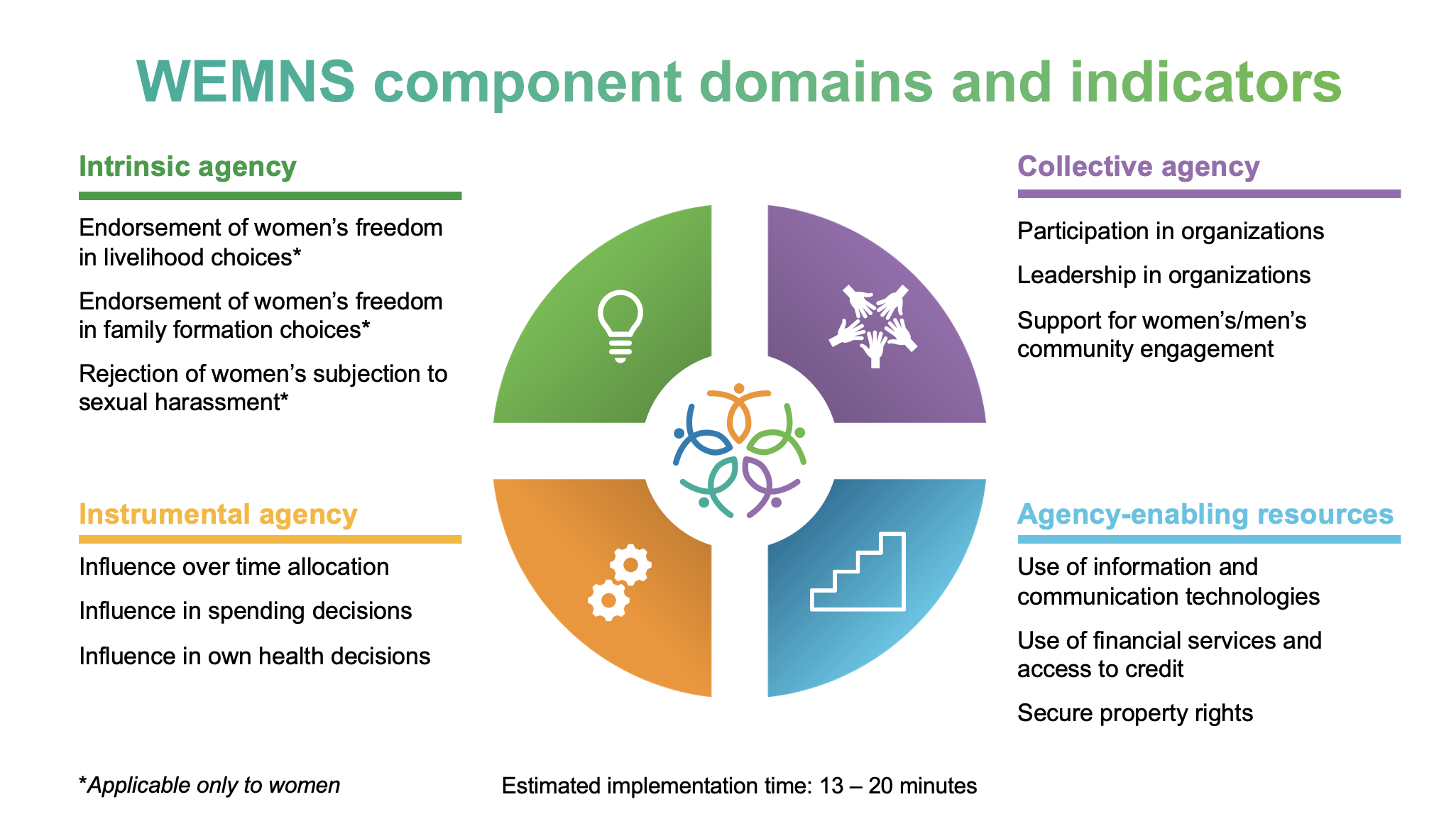

1. Scored 0 in an index based on 3 dimensions of the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) (Malapit et al. 2019) indicating that they were not empowered in any of the dimensions of instrumental, intrinsic or collective agency.

2. Willingness-to-pay was estimated using an incentivized Becker-DeGroot-Marschak mechanism.