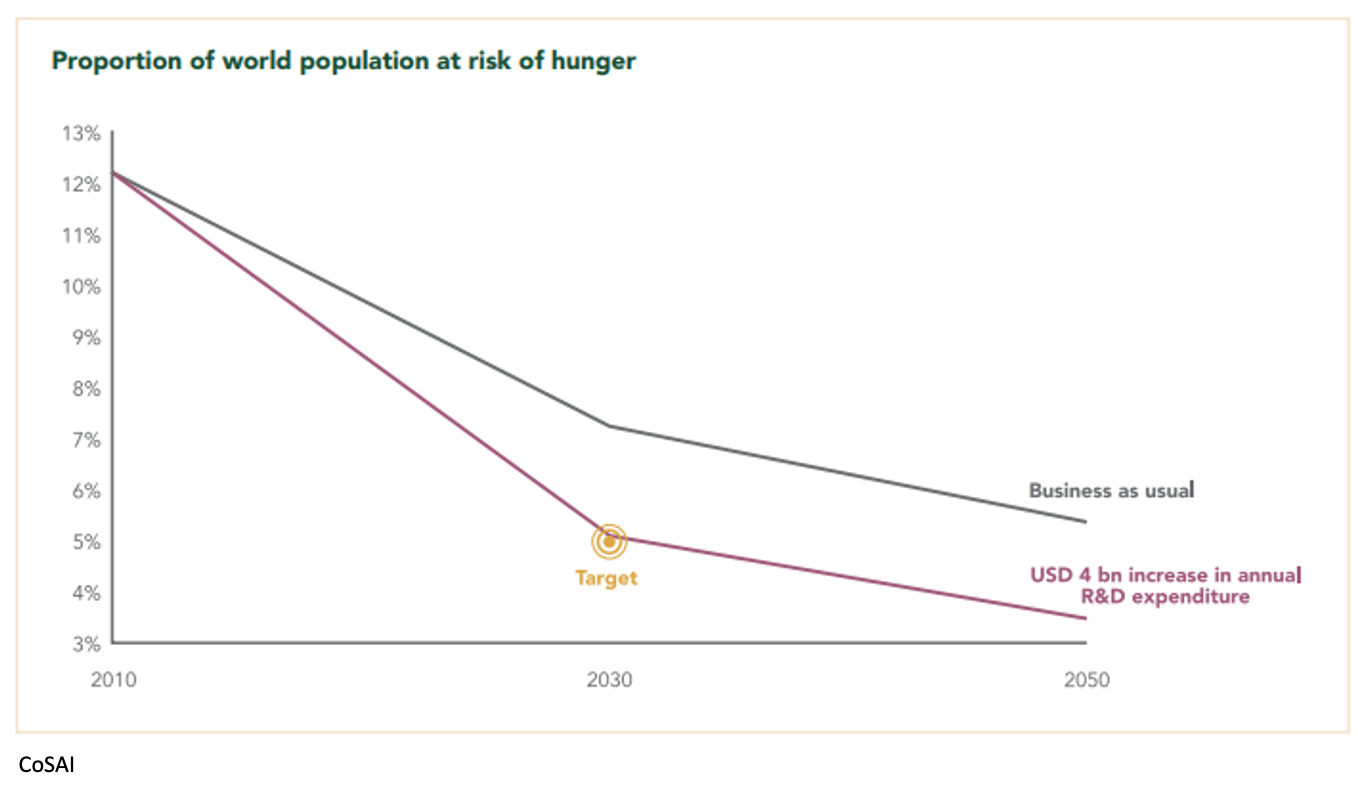

Increasing public and private investment in agricultural research and innovation by only $4 billion per year would achieve Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2) in East Asia, South Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean and reduce the risk of hunger from 24.3% to 11.8% of the population of Africa south of the Sahara. This is one of the insights from a new report from the Commission on Sustainable Agriculture Intensification (CoSAI) and the Transforming Agriculture for People, Nature and Climate campaign, with the work of IFPRI researchers using the institute’s IMPACT model.

The report finds that a total of $15.2 billion annual investment in research and innovation in sustainable agriculture intensifcation can have wide-ranging benefits—helping to meet future food demand, supporting climate action under the Paris Agreement, and fostering continuing development in the Global South. These investments—only a fraction of the estimated $700 billion spent annually on subsidizing global agriculture—can play a key role in sustainably transforming food systems, a central focus the upcoming UN Food Systems Summit.

IFPRI researchers modeled future scenarios to estimate the global “investment gap” in public and private spending on innovation in the Global South, focusing on the areas of greatest need and with the greatest potential for returns. Globally, agriculture faces many challenges. It must keep up with demand as the world’s population rises past 9 billion by 2050, and as climate change makes it harder to grow food in many areas. It must also use fewer inputs and less land in order to save precious water, reduce emissions, and reverse deforestation.

Currently, agriculture is a major contributor to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The report shows that by investing more in agricultural innovation—from R&D to scaling, policymaking, institutions, and infrastructure, agricultural systems can become more efficient, productive, and sustainable, becoming part of the solution in addressing the climate crisis. Such changes mean agriculture would support the pressing hunger, climate, water, and economic objectives of the coming decades.

Benefit from a boost to the global economy

There are also strong economic reasons for higher investment in agricultural research and innovation. Spending $4 billion more each year on R&D would boost the GDP of countries in the Global South by $1.7 trillion a year by 2030, and by $9.1 trillion a year by 2050, a significant return on investment. Modeling also predicts a 16% drop in the prices of major food crops by 2030, relative to business as usual, making nutritious food more affordable to households globally.

Start with $4 billion a year to reduce the risk of hunger

For maximum effectiveness, the $4 billion per year of additional investment in agriculture research and innovation should be balanced across national and international public and private research, the major contributors to current innovation investment in the Global South. Without balanced investments, modeling shows, attempts to reduce the risk of hunger around the world are likely to fall well short.

Add $6.5 billion a year for climate action

The study also makes clear the scale of the challenge posed by climate change. The extra investments in research and innovation will help agriculture cut GHG emissions, but not enough to meet the principal ambition of the Paris Agreement: Keeping global warming from surpassing 2°C above preindustrial levels by 2100. To approach this goal, agriculture needs an additional $6.5 billion investment each year in climate-smart technologies at scale that will reduce and sequester emissions.

Taking these urgent climate needs into account and ensuring sustainable agriculture investments play their role as part of the solution, the investment gap becomes $10.5 billion per year—however, that amount alone is not sufficient to limit warming to 2°C. The problem is continued land use change. With a growing population requiring more conversion of land to farmland, the study estimates that agriculturally-induced deforestation will not be halted by 2050—a goal necessary to hit the 2°C target—but innovation will at least slow the rate at which forest is lost. This means that above and beyond the $6.5 billion investments, zero land use change from agriculture must be achieved by promoting sustainability policies and investments in related sectors.

Invest another $4.7 billion a year to save water and nutrients

The overuse of water is also a serious global problem, targeted for action by SDG 6. The study suggests an additional $4.7 billion each year could lower agricultural water use by 10% in less than a decade. This investment would also reduce agricultural nitrogen pollution by 21% and phosphorous pollution by 14%.

Put together, these investments total $15.2 billion annually—a modest amount in global economic terms that can have significant impacts. A rapidly expanding population, increasing pressure on finite resources, a changing climate, and the ever-present global vulnerability to pandemics and financial instability all mean action with targeted environmental and social objectives is urgent. The evidence shows that by filling this annual $15.2 billion funding gap, the global community can reduce some of these instabilities, address the current problems facing our global population, and foster a sustainable future for generations to come. The time to sustainably invest is now.

Find out more about the investment gap study here.

Uma Lele is President-Elect of the International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE); Mark Rosegrant is Research Fellow Emeritus with IFPRI’s Director General’s Office. A version of this post appears on the CoSAI website.