In 2017, an estimated 124 million people faced crisis-level food insecurity or worse, up from 108 million in 2016. This rise in food insecurity has been driven by ongoing conflict and persistent drought, two trends that are expected to continue in 2018. This means that the number of people facing acute food crises will likely continue to rise.

These alarming findings were presented at IFPRI’s April 27 Washington, D.C., launch of the 2018 Global Report on Food Crises, produced by 12 leading global and regional organizations and released by the Food Security Information Network (FSIN). Panelists at the event emphasized the need for a coordinated global response at both the humanitarian and the development levels.

FSIN

Rob Vos (Director of IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division), David O’Sullivan (Ambassador and Head of European Union Delegation to the United States), and Neven Mimica (Commissioner of International Cooperation and Development for the European Commission) all stressed the crucial role of development aid in preventing food crises from occurring in the first place, in contrast to humanitarian assistance that arrives after the fact.

“Humanitarian response can attenuate a food crisis—not prevent it or keep it from getting worse,” Vos said.

FAO Senior Strategic Advisor on Resilience Luca Russo, a FSIN steering committee member, presented some of the report’s key findings: The rise in numbers of food-insecure people is acute in countries with ongoing conflicts including Yemen, northern Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, and Myanmar. Drought and persistent poor harvests, connected to climate change, have driven up the numbers in eastern and southern Africa. Overall, the number of people on the verge of famine has also increased.

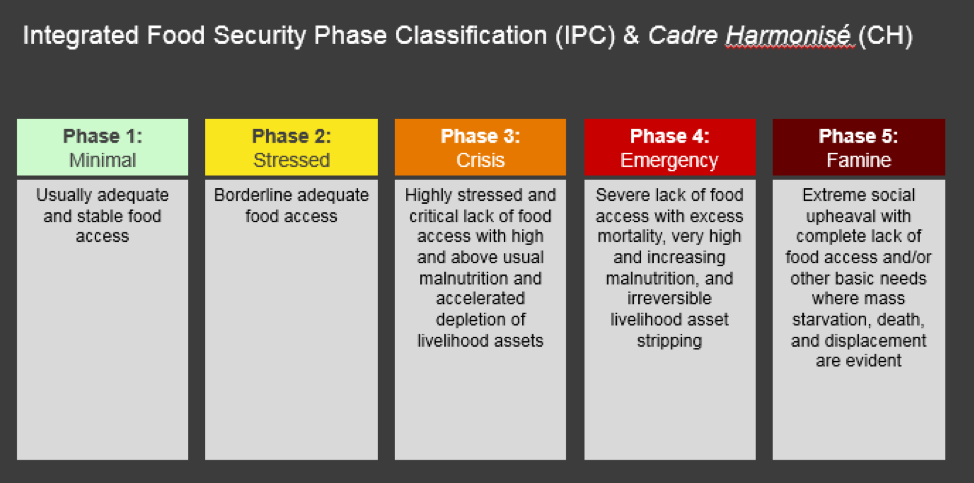

In discussing food crises, Russo said, it is important to understand what that means for people on the ground; for that reason the report draws on data from the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) system and the Cadre Harmonisé (CH) system, which provide clear indications of existing and worsening food insecurity.

Despite a long-term trend in improving data, Russo noted that problems remain. In particular, the report lacked data on possible food crises in several countries (Venezuela, Eritrea, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) even though acute food insecurity likely exists in these countries.

Russo noted that the report is intended to be a global public good, reflecting the work of the FSIN as a global network rather than one single organization.

FSIN

The event then turned to a panel discussion including Dominique Burgeon (Director of Emergencies at the Food and Agriculture Organization), Beth Dunford (Assistant to the Administrator, Deputy Coordinator for Development for USAID’s Feed the Future), and Arif Husain (Chief Economist for the World Food Program).

Dunford suggested ways in which stakeholders can turn from a focus on humanitarian relief to a focus on prevention and resilience. For instance, USAID has made efforts to shift its institutional view of food crises to recognize the need to invest in longer term solutions, particularly in vulnerable areas of the world, she said.

Thanks to technology, Husain said, there is more information regarding ongoing and developing food crises available than ever before. However, that information must be translated into action. “If we can see more, can we do more?” he asked. Husain recommended an “ask less, but ask often” approach to data collection in conflict-affected areas—meaning that collecting less in-depth but more high-frequency data is more useful in rapidly changing situations. And while gathering real-time data is crucial, that data should also be context-specific, he noted, and should constitute a global public good for both humanitarian aid and development aid.

Burgeon said that the world will continue to “keep accumulating people on the cliff of famine”—unless development actors become engaged much earlier, not just to prevent emerging crises but to build resilience. He emphasized the role of global networks, such as the Global Network Against Food Crises under the FSIN, in establishing a coordinated approach in which institutions around the world work together to address food security challenges, as “resilience is not the business of a single agency.” Through informed, evidence-based programs, he said, such global networks can better mobilize multiple actors to respond to developing crises and prevent acute food insecurity.

“Famine is a policy failure,” IFPRI Director General Shenggen Fan said in his concluding remarks. “But if it is manmade, that means it can also be fixed by mankind.”

Sara Gustafson is a Communications Specialist in IFPRI’s Markets, Trade and Institutions Division.