The following post was originally published on the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security’s News Blog

Kenya appears to be booming. In the last decade, shiny office buildings have sprung up along the edges of equally shiny superhighways, offering new connections and untold promises to people in cities and rural areas. Every day brings new opportunities, such as the discovery of oil and the more recent discovery of aquifers in the desolate northern Turkana region. Globally, Kenya’s reputation for lions and giraffes may be supplanted by its exports of fresh flowers and produce, the product of a thriving horticulture industry. The country’s GDP is rising, but the truth is that agriculture’s contribution to Kenya’s economy is on the decline. This is troubling, because 75 percent of the country’s labor force is still devoted to agriculture, and the vast majority of Kenya’s farmers rely on rain to feed their crops. And a new challenge looms large: climate change.

Kenya’s agriculture is vulnerable to climate change, but there may be reasons for optimism, according to a new comprehensive analysis prepared by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Central Africa (ASARECA).

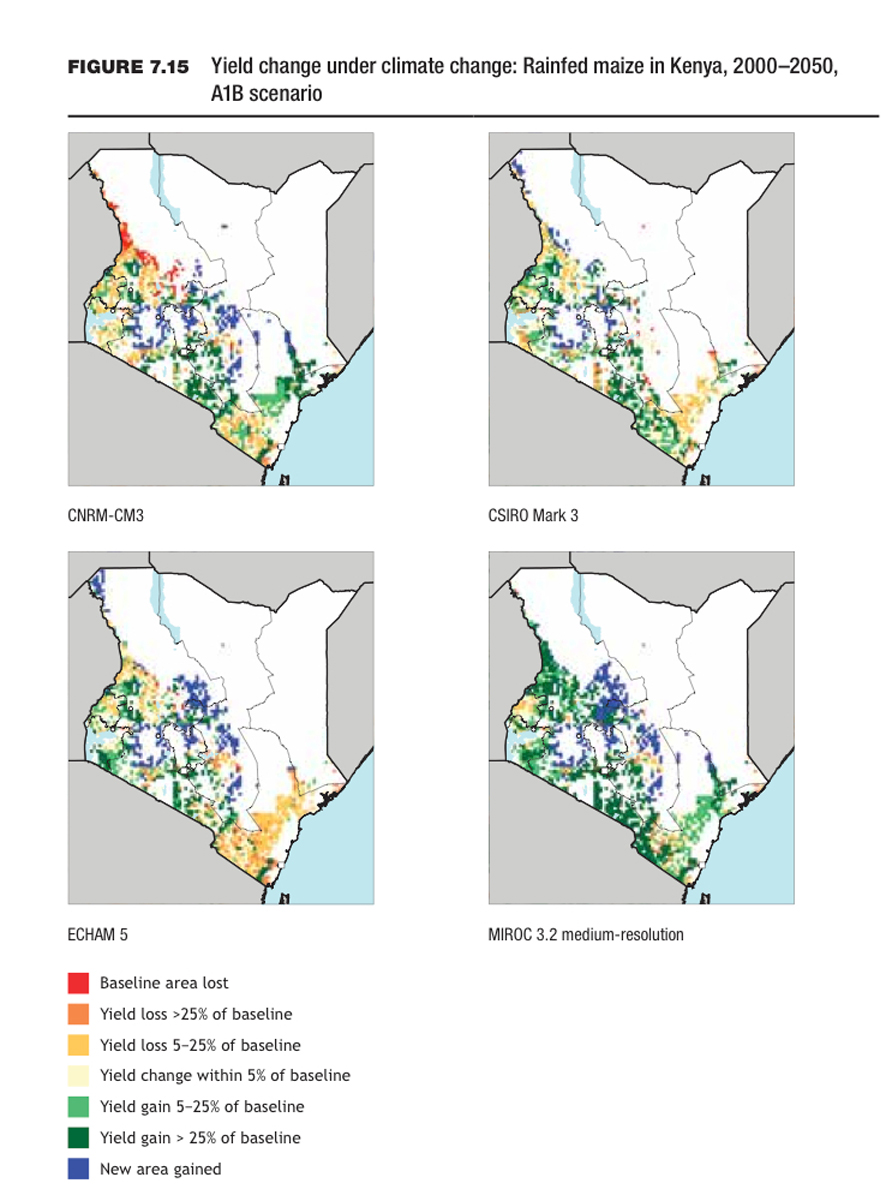

The study, which was funded in part by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), offers a detailed snapshot of Kenyan agriculture now and predicts how shifting demographics and future growing conditions could affect food security and crop production. The analysis includes projections for crop yields, population growth, and income, as well as scenarios for climate change from four different models. When taken together, these projections reveal a number of insights about Kenya’s future.

Dominance of rainfed agriculture puts farming at risk

The Kenyan horticulture industry’s lifeblood is the water of Lake Naivasha, and the dramatic landscape around the lake, which sits in the Rift Valley, is marked by large greenhouses, their white plastic covers flapping in the wind. A symbol of growth and globalization, these greenhouses also stand out as a profitable exception: irrigated agriculture only accounts for 1.7 percent of the country’s total land area under agriculture, according to the report. There are already plans to change this: Kenya’s National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) 2013 – 2017 aims to increase the area of land under irrigation to up to 1m hectares from the current 140,000 ha.

Population rising but GDP must catch up

The report notes that populations are projected to rise anywhere from 75% to 150% by 2050, increasing pressure on productive resources, which could lead to food insecurity. There is also an increasing trend towards urbanization. Though GDP is on the rise, growth rates may remain very slow unless Kenya implements policies to stimulate economic growth while concurrently reducing the rate of population growth.

Improve farmers’ capacity to adapt

The agricultural sector has low capacity to adapt to climate change in Kenya, according to the report, due to limited economic resources, heavy reliance on rainfed agriculture, frequent droughts and floods, and general poverty. The underlying causes for low adaptive capacity must be addressed.

Climate change may bring new opportunities

All climate models predict that rainfall will increase in certain arid and semi-arid regions of Kenya (see image below). This would allow maize to be grown in places that previously have been too dry to support the crop. Policies to encourage this can be explored, though be mindful of sensitive issues related to land tenure and migration.

Planning for the future, together

Adaptation needs good planning in order to minimize potential damage and take advantage of new opportunities, and uncertainty is no excuse for inaction:

“Despite the uncertainties, the science clearly shows us that big changes are likely to occur and we need to have a number of options available so farmers can adapt to the new conditions they will encounter,” said Michael Waithaka, a co-author of the report, who leads the Policy Analysis and Advocacy Program at ASARECA.

Putting research into action

Today and tomorrow, some of Kenya’s most capable scientists, and most powerful policy makers are discussing the future of agriculture, at a meeting on the shores of Lake Naivasha. This meeting aims to build consensus on the priority actions for agriculture proposed in the National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP). Some of the climate-smart farming innovations being considered can already be seen in Nyando, western Kenya, where CCAFS researchers, development partners and farmers are jointly identifying and testing different tools and approaches in Climate Smart Villages.

When the Naivasha participants present their report on the priority actions to be taken forward, as well as a resolution on how to take these forward, they will hopefully pave the way towards a more climate-smart and prosperous future.

Related materials