In rural markets of developing countries, agricultural commodity prices exhibit seasonal fluctuations, with low prices at harvest, followed by steady rises to an annual high shortly before lean-season planting. Ideally, an economically rational farmer should delay sales until prices recover. Instead, it is often observed that smallholder farmers sell most of their marketable surplus right after harvest, and then end up repurchasing the same commodities for family sustenance later when prices are higher.

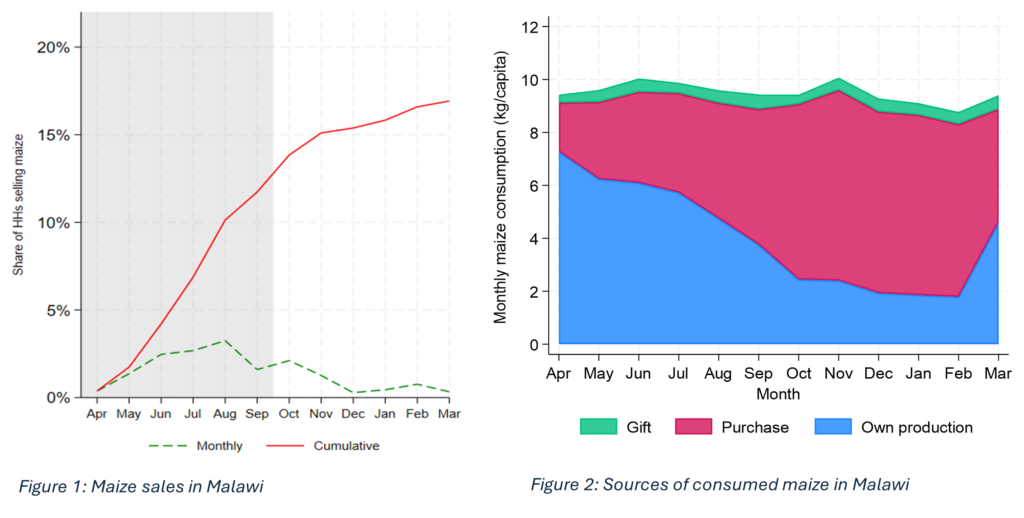

Smallholder farmers in Malawi are no exception to this puzzle. In Figure 1, maize sales among Malawian households start to increase at harvest time (April/May) and peak in August. Right after this (September to February), purchased maize becomes the main source of maize consumed by households (Figure 2).

The literature suggests many possible reasons why farmers choose to sell early at low prices and buy back later at higher prices. Most explanations focus on economic and infrastructural factors such as inadequate storage technologies, risk aversion, as well as liquidity constraints.

In a study on smallholder farmer market participation conducted in 2022-2024 in Malawi, we build on literature related to budget neglect and motivated reasoning in spending decisions to test two behavioral explanations for the sell-low-buy-high paradox, using two household planning-based interventions, to find which is most important.

The budget neglect explanation focuses on the household expenditure side and assumes that households are constrained in their cognitive capacity to accurately predict their full set of expenditures over an extended period, leading them to foresee too little and underestimate how much money they need in the future. For example, immediately after harvest, they may budget for fresh seed and fertilizer—essential for the next planting—but may forget to budget for pesticides and insecticides, which are less essential and difficult to foresee at the time. Such budget neglect leads farmers to sell more early on and save too little for later in the year.

The motivated reasoning explanation focuses on the household income side and assumes that the sell-low-buy-high behavior is driven by impatient farmers who engage in discretionary spending based on their reasoning that they can expect higher future income. Because farmers expect too much in the future, they end up selling more than they should immediately after harvest, without guarantee they will have additional income for future spending needs.

Two planning-based interventions to test the behavioral explanations

To test the above hypotheses, we implemented two planning-based interventions through a parallel randomized controlled trial among 3,500 smallholder farm households in Malawi. These households produce (a mix of) maize, groundnuts, and soybean, from which part is destined for the market.

The first intervention (T1), a household expenditure budget, tested the role of budget neglect in explaining the sell-low-buy-high paradox. Farmers randomly assigned to this treatment arm were taken through a detailed budgeting exercise immediately after harvest by a trained enumerator who sat with the household head and filled in a budget matrix of projected household expenses for each month in the coming year.

The second treatment (T2), a household selling plan, used commitment to test the motivated reasoning hypothesis. Farmers randomly allocated to the second treatment arm received a sales planning intervention in which a trained enumerator sat with the household head and planned how much of each crop they would sell each month during the coming year. For each planned sale, the household head is also asked to commit to a minimum price.

The idea behind both interventions was to encourage delayed sales into higher price periods by helping farm households think through future expenses and income.

The impact of the interventions on a variety of outcomes—including stocks held and sales/purchases made at given point in time—was compared to outcomes of a control group that received no intervention.

Findings

Overall, the interventions, particularly T2 (sales planning), helped mitigate the sell low-buy high phenomenon by promoting better stock management and sales timing among farmers. We found that for maize, T2 led to higher stocks immediately after harvest and encouraged delayed sales into higher price periods, reducing the need for later market purchases.

T1 (budgeting) showed mixed results, with some positive impacts on stock levels but less consistency in influencing sales timing. For soybean, T2 was notably effective in maintaining higher stocks and delaying sales, while T1’s impact was less clear. Groundnuts showed similar trends, with T2 increasing stocks entering the hunger season but showing inconsistent effects on transaction timing.

We did not find any effects on selling and purchase prices, but, considering both revenues and expenses, the sales plan intervention improved net positions for both soybean and groundnuts. Net positions for maize were marginal due to substantial purchasing.

Significance

Overall, our results find some evidence that behavioral-related factors such as budget neglect and motivated reasoning explain the sell-low-buy-high marketing behavior among smallholder farm households. Furthermore, our study suggests that an intervention that focuses more on planning of sales is more effective than an intervention that focuses on expense planning.

This finding is potentially important for policymakers and practitioners: We found that budgeting is something that is often used by nongovernmental organizations during extension and training programs. Our study suggests that a sales plan, which was far easier to prepare than a complete budget, is likely to be the more cost-effective of the two approaches.

Joachim De Weerdt is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division, based in Lilongwe, Malawi; Brian Dillon is a Professor at Dyson School, Cornell University, Ithaca, United States; Emmanuel Hami is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division based in Lilongwe, Malawi; Bjorn Van Campenhout is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Innovation Policy and Scaling (IPS) Unit based in Leuven, Belgium; Leocardia Nabwire is an IPS Research Analyst based in Kampala, Uganda. This post is based on research that is not yet peer reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.