Households living in extreme poverty face a complex set of constraints that are difficult to escape. Existing resources often must go to meet immediate needs, leaving little or no money for investments with longer-term benefits; households may not own assets that could be used to generate a sustainable income stream, or have access to credit to purchase them. In addition, the high levels of stress often associated with poverty may limit people’s knowledge, attention, and/or psychosocial capabilities.

To address these complex challenges, layered poverty “graduation model” interventions that simultaneously address several barriers have shown promise in enabling households to increase their income and enhance their well-being along multiple dimensions (Banerjee et al. 2015, Bandiera et al. 2017). Such approaches encompass large asset transfers, regular monthly payments for consumption support, access to savings technologies, and regular training and household coaching. However, the effectiveness of such interventions at larger scales has not been widely explored, and given that they are intensive and center around asset transfers valued between $500 and $1000, there may be important trade-offs between program capacity and feasible scale.

Recent IFPRI research explores the effectiveness of a new, light-touch graduation model implemented at scale in rural Ethiopia, finding it has modest but meaningful impacts on asset accumulation and savings. The program, Strengthen PSNP Institutions and Resilience (SPIR), targets household beneficiaries of the Ethiopian government’s Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP), which provides food and cash transfers to roughly the poorest 20% of rural households in targeted food-insecure districts during the agricultural off-season. Building on the base of PSNP support, SPIR’s multifaceted graduation model includes both livelihood and nutrition interventions and centers around the formation of village-level savings groups— local collectives where households can jointly save and that also serve as a vehicle for program trainings. We define this model as lighter touch compared to other graduation models given a reduced set of interventions and an asset transfer that is notably lower in value; however, SPIR is also delivered at relatively large scale, serving more than 150,000 households.

Our study tracked a sample of 3,314 households in the Amhara and Oromia regions, a broad area served by SPIR, from 2018 to 2021. Nearly 200 communities were randomly assigned to receive different bundles of interventions in order to assess their relative effectiveness. The full trial included four experimental arms.

The first two experimental arms included the full set of livelihoods interventions: A one-time livelihoods transfer valued at around $370 provided to the poorest 60% of sample households within each community; training on livestock production and marketing; and the formation of village-level savings groups.1 The transfers consisted of either cash or a poultry package (16 chickens and complementary inputs) of comparable value. These were randomly assigned at the cluster level, creating the two experimental arms. The third experimental arm included savings groups and training only; the fourth served as the control arm. In addition to the livelihoods interventions, all treatment arms except the control received nutrition behavioral change counseling (BCC). Finally, all households were receiving the base PSNP support of cash and food transfers.

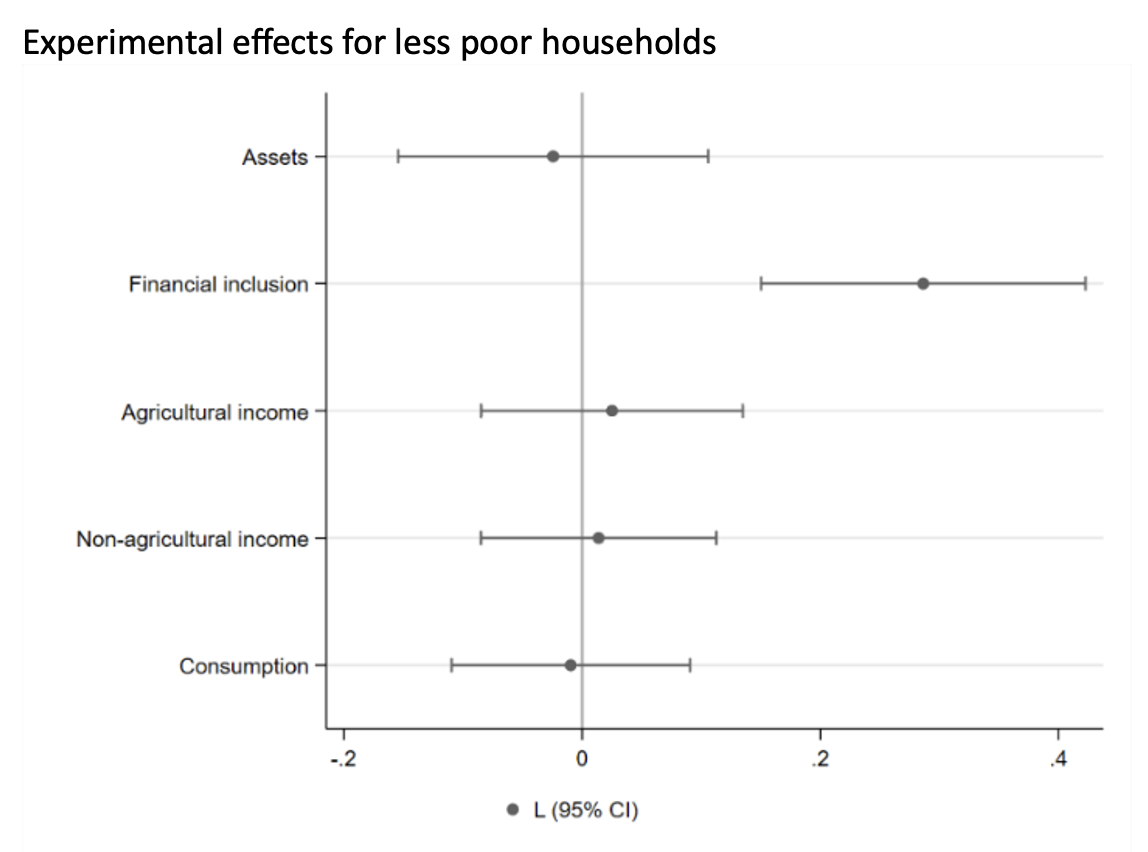

Our main findings suggest that the full set of livelihoods interventions enabled households to accumulate some modest additional assets (primarily livestock), as well as increase their level of savings and access credit. There is also some evidence of increased income from sales of livestock and livestock products specifically, but the overall level of consumption did not increase. Figures 1 and 2 summarize the experimental effects for the primary outcome families of interest, comparing each experimental arm to the control arm. (The “L” arm denotes the arm that received savings groups and training only).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Source for both figures: Leight et al, 2023.

Interestingly, all of these effects are broadly consistent for both poultry and cash recipients. There is no evidence that the type of transfer received had a significant impact on outcomes, suggesting that the choice of transfer modality can reasonably be based on local conditions, preferences, and implementation constraints.

For the more limited set of interventions (savings groups and training only) the only significant effect observed was an increase in savings. Without receiving any larger transfer of cash or poultry, these households were not able to accumulate any additional assets, identify new sources of income, or consume more.

Our findings suggest that implementing a light-touch graduation model at scale generally did not lead to an exit from poverty for the targeted households—despite the fact that previous, more intensive models have shown significant effects on poverty in the short- and long-term. Nevertheless, we suggest that this approach is arguably more feasible than other large-scale efforts. In Ethiopia, even sustaining the base PSNP at a large scale has proved extremely challenging in recent years, and implementing transfers of up to $500 or $1000—as is seen in some of the most successful graduation model programs—is likely not feasible. However, the fact that this more feasible model has only limited effects on reducing poverty suggests other policy tools will be needed to stimulate an exit from poverty, particularly in rural areas increasingly affected by conflict-related and climatic shocks.

Jessica Leight is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Poverty, Gender, and Inclusion Unit. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed.

Referenced Discussion Paper:

Leight, Jessica; Alderman, Harold; Gilligan, Daniel; Hidrobo, Melissa; and Mulford, Michael. 2023. Can a light-touch graduation model enhance livelihood outcomes? Evidence from Ethiopia. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2203. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.136972

This work was supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the IFPRI-led CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM).

1. More specifically, transfers were designed to target 10 out of 18 households in each cluster randomly assigned to a transfer, or 56%, and the achieved targeting was 58% of households in those clusters. The precise value of the transfer was $374 in 2017 purchasing power parity dollars.