Myanmar—its economy, society, and political system—finds itself in tragic circumstances, with deep, prolonged, and multifaceted hardships falling upon its people.

During the 2010s, the country made substantial progress addressing some of its longstanding problems. Poverty and malnutrition were still widespread (in 2015-16, one third of preschool children were stunted and three quarters had inadequately diverse diets), but economic growth was strong, and the democratic government and its development partners were rolling out and scaling up social protection programs for the first time in Myanmar’s history.

That progress came to an abrupt halt in 2020. First, COVID-19 led to rising poverty and food insecurity; then the February 2021 military takeover plunged the economy into an unprecedented crisis, with GDP contracting by an astonishing 18% that year. A violent civil war erupted, along with rising crime, food inflation, financial turmoil, shortages of essential foods, and a complete collapse of many essential government services, including social protection.

It isn’t easy to find a ray of hope in Myanmar’s tragedy, but a study just published in The Journal of Nutrition finds a glimmer of it—demonstrating that nutrition-sensitive social protection can provide significant nutritional resilience even after a program ends, and even in an exceptionally dire economic crisis.

The study reevaluates the impacts of a maternal and child cash transfer (MCCT) program implemented over 2016-2019. The program was funded by the Livelihoods and Food Security Fund (LIFT) and implemented by Save the Children in rural villages of Myanmar’s rural dry zone. It was originally evaluated by Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) and researchers at Duke University (Erica Field and Elisa Maria Maffioli) in what was called the LEGACY study.

Mothers in LEGACY implementation villages received monthly cash transfers of around $10.50 per month (in 2018 USD) from the start of their pregnancy until their child was 2 years old—i.e., the first 1000 days of a child’s life, the period in which maternal and child nutrition are most crucial to future development. A sub-sample of families also received social and behavior change communication (SBCC) sessions to improve knowledge and change key behaviors on nutrition and hygiene. Hence the evaluation was able to experimentally compare both CASH and CASH+SBCC to a control group of mothers who received neither cash nor SBCC.

The original LEGACY evaluation study found that the combination of CASH+SBCC significantly reduced the proportion of children stunted, while CASH alone had no statistically significant impact on stunting. Nutrition education (SBCC) interventions appeared to complement cash by encouraging mothers to improve children’s diets, especially their intake of nutrient-dense animal-sourced foods and pulses and beans.

So far so good, but perhaps not too surprising—an IFPRI study from Bangladesh reached very similar conclusions on the synergistic effects of CASH+SBCC on stunting reduction. However, shortly after the program ceased in 2019, that wave of crises hit Myanmar, starting with COVID-19, then deepening much further with the military takeover and ensuing civil war. Figure 1 shows that income-based poverty in a sample of rural households from the dry zone dramatically increased from 28% in January 2020 (just before COVID-19) to anywhere between 50% and 70% over the course of 2020 and 2021.

Figure 1

In this extremely fragile economic environment, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and LIFT supported IFPRI’s Myanmar Agricultural Policy Support Activity (MAPSA) and IPA to monitor trends in poverty (as in Figure 1), food insecurity, dietary diversity, and other important welfare indicators in the original LEGACY sample of CASH, CASH+SBCC and CONTROL households. This allowed us to evaluate LEGACY’s post-program impacts on diet diversity and food security some 1-4 years after households stopped receiving CASH and SBCC, and to explore potential mechanisms of impact, such as program-related impacts on household incomes.

What did we find?

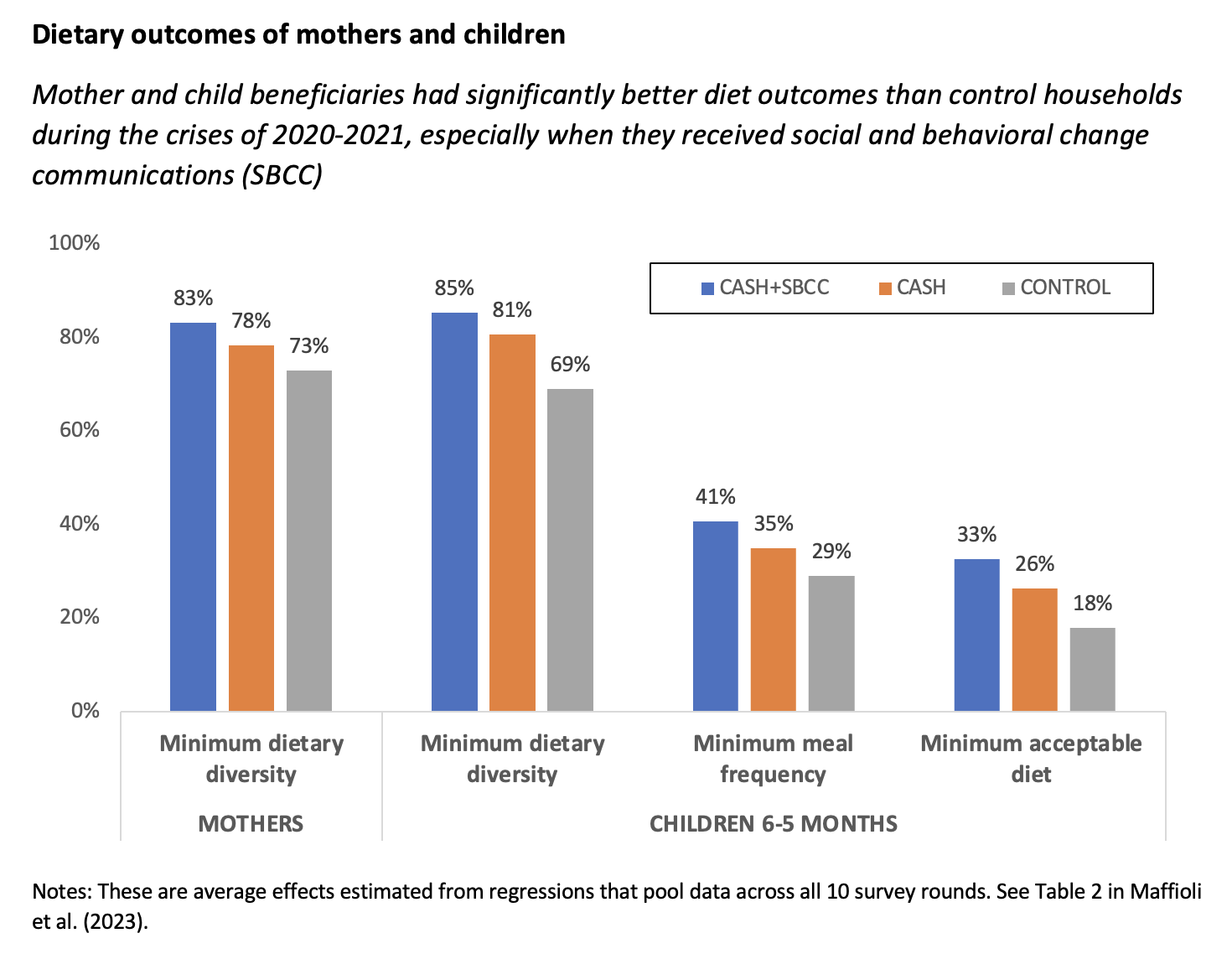

Encouragingly, both CASH and CASH+SBCC arms reported significantly lower food insecurity, more frequent consumption of nutritious foods, and more diverse maternal and child diets compared with households in the CONTROL group (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The improved dietary outcomes were larger for mothers and children exposed to CASH+SBCC compared with CASH, as was their monthly household income. The effects of CASH+SBCC on diets relative to CONTROL households were particularly large: CASH+SBCC women were 10 percentage points more likely to have an adequate diet across all survey rounds, while children aged 6-59 months were around 18 points more likely to have an adequately diverse diet, and around 11 points more likely to achieve minimum meal frequency. Interestingly, CASH+SBCC households also reported higher incomes than CASH and CONTROL groups, perhaps suggesting that SBCC empowered households to make productive economic decisions, although this is only a conjecture.

In implementing a phone survey in lieu of in-person interviews and health assessments, we were not able to monitor child nutrition outcomes to see if the original LEGACY evaluation’s findings on larger stunting impacts in the CASH+SBCC group was sustained in 2020-2021. But we were able to explore the LEGACY evaluation’s evidence on greater consumption of nutrient-dense animal-sourced foods and pulses. This is important because animal sourced foods are known to reduce the risk of stunting.

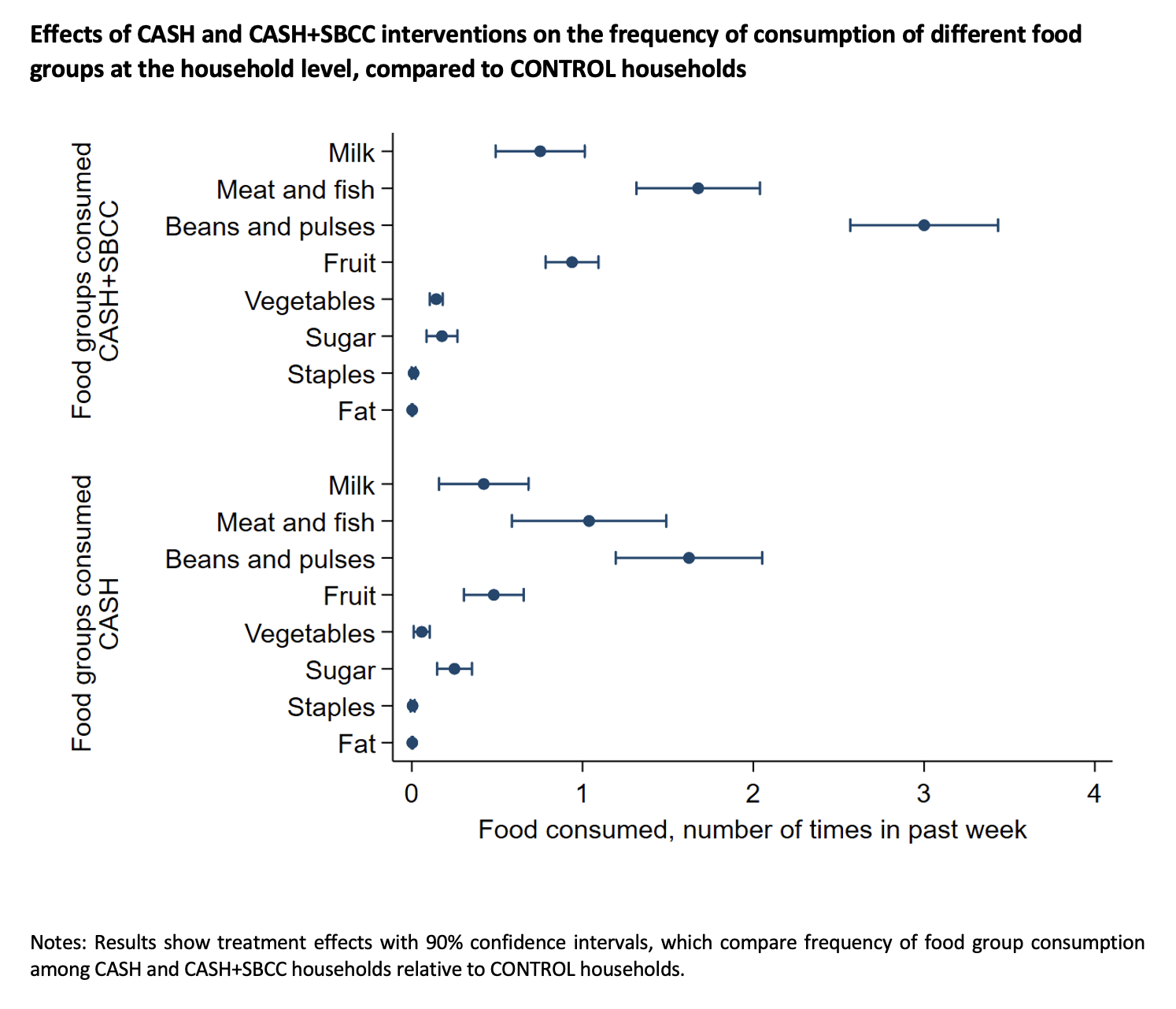

We found that CASH+SBCC households had much more frequent consumption of beans and pulses, meat and fish, fruit, and milk (Figure 3). For example, CASH+SBCC households consumed beans and pulses an extra three times per week relative to CONTROL households. CASH households also reported more frequent consumption of these foods compared to CONTROL households, although the magnitudes of these impacts are generally smaller than they are for the CASH+SBCC households.

Figure 3

This evidence clearly shows that maternal and child cash transfers with nutrition-related education can yield sustained benefits several years after the program ends, even in exceptionally adverse circumstances. Interestingly, an IFPRI study in Bangladesh also experimentally assessed cash, food and SBCC combinations some four years after the cessation of that program: There, too, CASH+SBCC yielded the greatest benefits. These post-program evaluation studies therefore strengthen the existing rationales for scaling up nutrition-sensitive social welfare programs—that they improve diets and redress malnutrition in the near term—by showing that they can also improve nutritional resilience in the longer term. In the context of our study, the program improved nutritional resilience even in the midst of a deep and prolonged economic, social, and political crisis.

In a better governance environment, the nutrition-sensitive program we evaluated would have been scaled up nationwide in Myanmar. As it is, the military government has not continued previous social protection programs or initiated new ones, and donor agencies and non-governmental organizations are facing major financial, logistical, and political barriers to implementing social protection independently and at sufficient scale, despite a huge increase in food insecurity and poverty since 2020.

However, these findings should encourage the already-accelerating momentum of digital cash transfers as a viable modality for assisting poor populations. One important question for future evaluations is to test whether nutrition education, typically conducted in-person, can also be delivered through ICTs in tandem with digital cash transfers, and whether such approaches can produce the near-term and long-term nutritional benefits evident from the LEGACY trial.

Derek Headey is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division working with IFPRI’s Myanmar Strategy Support Program and the Myanmar Agricultural Policy Support Activity (MAPSA); Elisa Maffioli is an Assistant Professor of Health Management and Policy and of Global Public Health at the University of Michigan.