Intimate partner violence (IPV) is the most pervasive form of violence globally, with one in three women physically or sexually abused by a partner in her lifetime. IPV has multiple malign consequences for the physical and mental health of women, as well as a range of adverse effects on their children. While these consequences are well documented, there is less evidence on the effectiveness of policies and programs in reducing IPV in the developing world.

Drawing mainly from work in Latin America, several recent studies find evidence that cash transfer programs, targeted primarily at women, can reduce IPV. Given that cash transfer programs are widespread around the world—implemented in over 130 countries and reaching approximately 718 million people globally—they represent a promising, scalable, globally-relevant approach to reducing IPV. However, important questions remain as to whether policymakers can generalize the existing findings to diverse settings and whether these programs provide a sustainable approach for IPV prevention.

Three case studies

Over the last 20 years, IFPRI has conducted numerous randomized evaluations of cash transfer programs throughout the developing world. Although reductions in IPV have not been the main focus of these programs or their evaluations, recently researchers have begun studying the unintended impacts of cash transfer programs on IPV. We present findings from several recent IFPRI studies. We identify three policy-relevant knowledge gaps related to the potential of transfer programs to reduce IPV, then address them drawing on case studies from three countries around the globe: Ecuador, Bangladesh, and Mali.

First, we note that transfer modalities other than cash, such as food and vouchers, are widespread around the world. These alternative modalities may serve some objectives better than cash, raising the question of whether there is a trade-off to using these modalities in terms of IPV impacts. The first case study in Ecuador asks the following question: Does the modality of transfer provided—food, cash, voucher—matter for impacts on IPV?

Second, most cash transfer programs do not continue indefinitely. If these programs are to be a sustainable solution to reducing IPV, their impacts must persist after the programs end. However, there is little rigorous evidence on the post-program impacts of cash transfers on IPV. Moreover, many cash transfer programs in the developing world include complementary programming such as training, but much of the evidence showing that cash transfer programs reduce IPV has been unable to distinguish the roles of these components. Given that the complementary programming may be logistically challenging and costly to implement, it is important to know if it is required for reductions in IPV. The second case study in Bangladesh asks the following question: What happens to IPV after a transfer program ends, and does it depend on complementary activities provided along with transfers?

Lastly, much of the evidence on cash transfers and IPV focuses on programs targeted to women in monogamous households. However, in some regions, targeting women may be viewed as contextually inappropriate. In parts of the developing world, particularly in Africa, diverse household structures such as polygamy are also common. The third case study in Mali asks the following question: What are the impacts on IPV when cash transfers are targeted primarily to men, and does it depend on household structure?

The programs

The transfer programs assessed in these three studies focused on household food security and child nutrition as primary objectives. However, they differed in terms of scale, target population, duration, transfer amount, transfer frequency, recipient, and complementary activities (see Table 1). Those in Ecuador and Bangladesh were small-scale pilot programs implemented by the World Food Program and had female recipients—designated adult women in Ecuador, and mothers of young children in Bangladesh. In Mali, it was a large government-implemented national cash transfer program whose recipient was the household head, usually male. All programs included complementary trainings on nutrition and other topics, but without any explicit focus on gender or violence. In Bangladesh, these trainings were part of a more intensive nutrition behaviour change communication (BCC) component.

Study designs

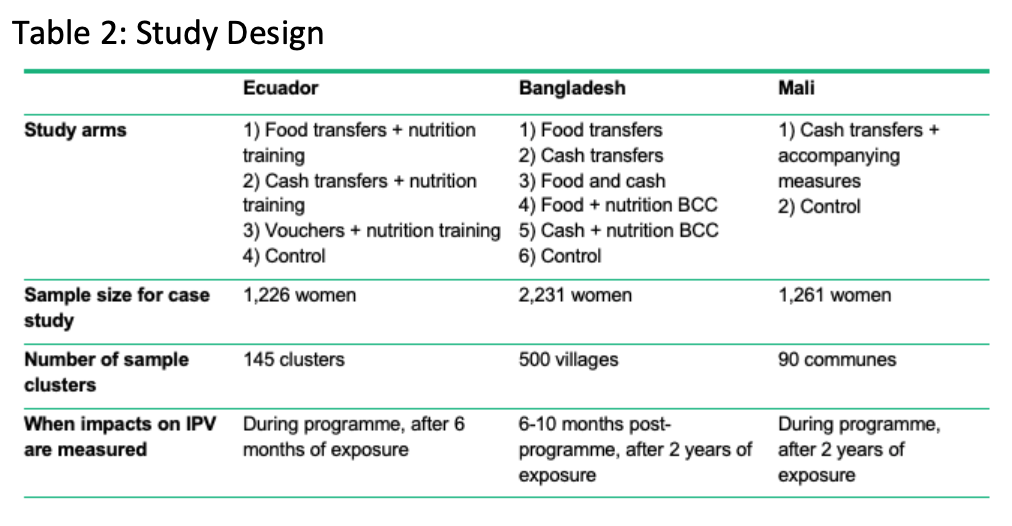

Each case study draws on a cluster-randomized control trial to measure the causal impacts of the transfer program on IPV, and mixed methods to understand what happens and why. All studies use the WHO Violence Against Women instrument to measure IPV, which was administered following the WHO protocol on ethical guidelines for conducting research on women’s experience with IPV. Table 2 summarizes key features of the case studies’ designs.

Results

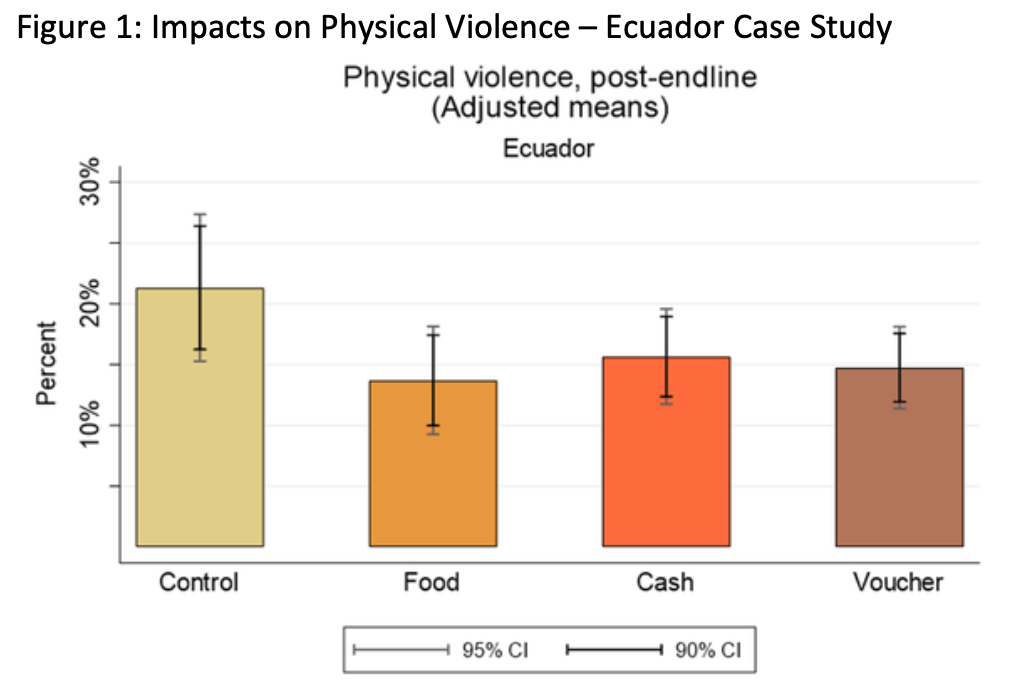

1. Does the modality of transfer provided matter for impacts on IPV? (Ecuador)

No, the modality of the transfer provided did not matter for impacts on IPV. All three modalities —food, cash, and voucher—led to significant reductions of 25-35% in physical violence.

Source: Hidrobo et al. (2016)1

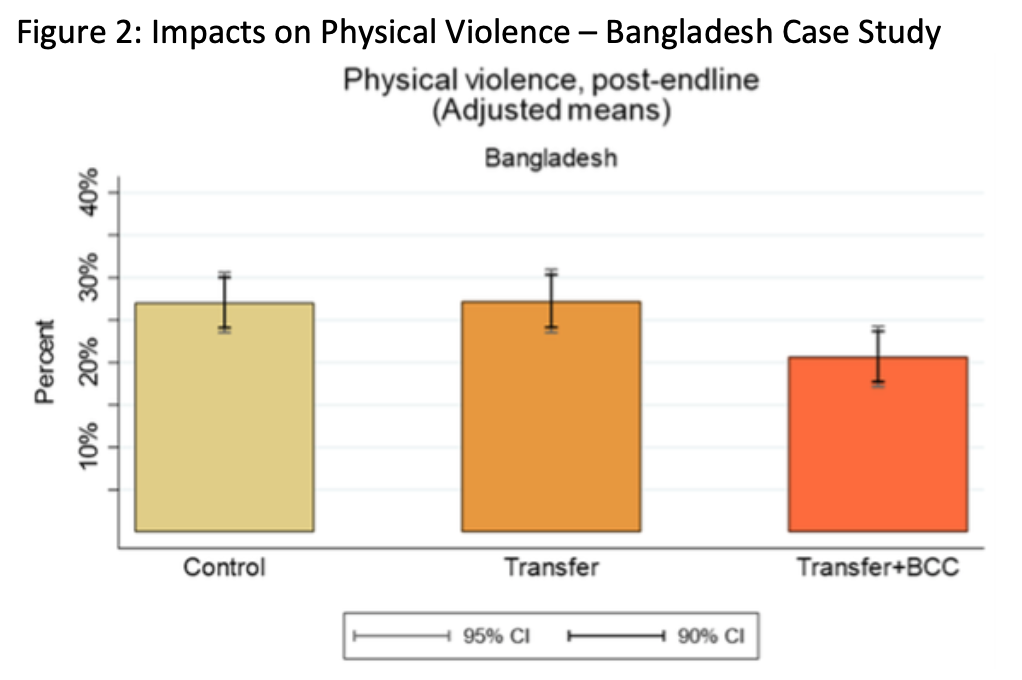

2. What happens to IPV after a transfer program ends, and does it depend on complementary activities provided along with transfers? (Bangladesh)

Six to ten months after the program ended, transfers + BCC led to a 26% reduction in physical violence, but there were no impacts from transfers only on IPV six to ten months post-program. BCC was required to sustain the impacts of transfers on IPV .

Source: Roy et al. (2018)2

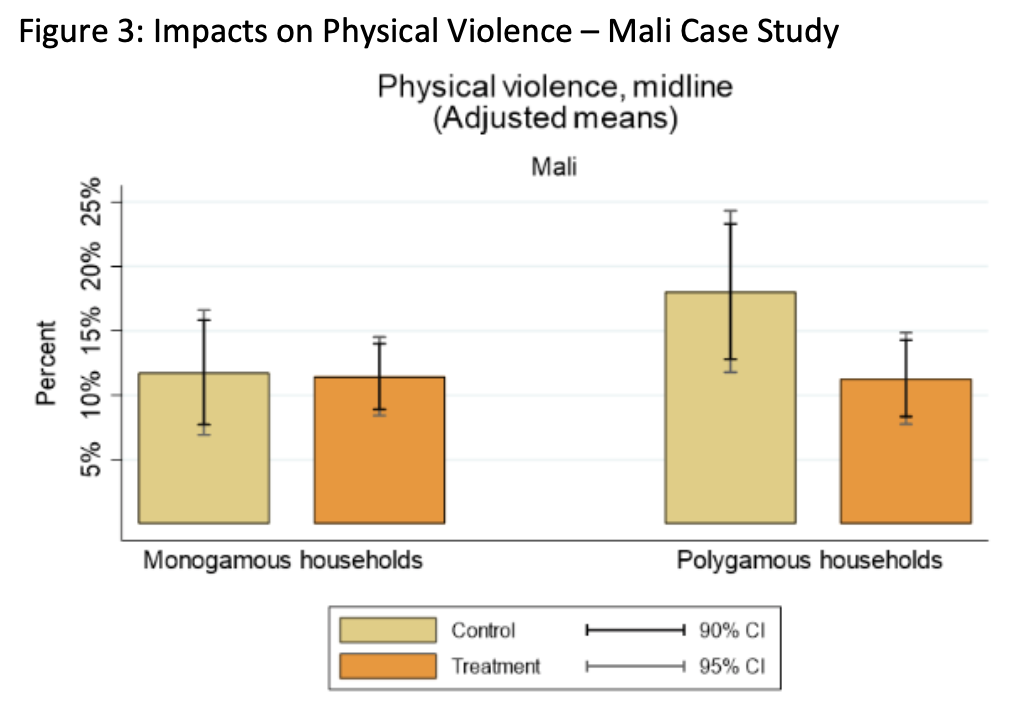

3. What are the impacts on IPV when cash transfers are targeted primarily to men, and does it depend on household structure? (Mali)

Impacts depended on household structure. Cash transfers led to a 41% reduction in physical violence in polygamous households, but they had no impact on monogamous households.

Source: Heath et al. (2018)3

Mechanisms

There are three pathways outlined in Buller et al. (2018) through which cash transfers can affect IPV.

- Economic security and emotional well-being, whereby cash improves a household’s financial situation, which reduces poverty-related stress and improves members’ emotional well-being, reducing men’s triggers for perpetrating IPV.

- Intra-household conflict, whereby cash may decrease or increase arguments and resulting conflict over the spending of money.

- Women’s empowerment, whereby cash targeted to women and complementary activities may increase a women’s bargaining power, making them less willing to accept violent behavior.

Across all three studies, we found evidence of one or more of these three pathways. Economic security and household wealth increased in all three case studies. In Mali, where we specifically measured emotional well-being, we also found reductions in stress and anxiety among men in polygamous households. Intra-household conflict appears to decrease in all three case studies. Quotes from Ecuador and Bangladesh suggest that conflict decreased because women no longer had to ask their husbands for daily money to buy food, and in Mali we found larger decreases in reported disputes among polygamous households than among monogamous households. Women’s empowerment improved in both Ecuador and Bangladesh, with evidence of increased control over money, agency, and social capital. However, we found no evidence of improvement in Mali, which is unsurprising given that the transfer was not targeted to women.

Policy implications

Despite diverse program features and contexts, we found commonalities across the three case studies. First, cash transfers reduced IPV in all three case studies, even though IPV was not the main focus of any program. Second, although there is theoretical potential for cash transfers to increase IPV, we did not find any evidence that the transfers increased IPV in these three studies.

In terms of program design, we found that the transfer modality does not matter for impacts on IPV, but complementary activities may be essential for sustaining impacts. Transfers targeted to men rather than women still have the potential to reduce IPV through improvements in economic security and reductions in intra-household conflict, but impacts depend on context and household structure.

Overall, these case studies show that cash transfers are a promising tool to sustainably reduce IPV throughout the developing world, but nuance is required in considering program features and context. Features and contexts of programs affect the pathways through which cash transfers affect IPV, and impacts on IPV may revert if the cash transfer program does not sustainably affect the pathways.

Melissa Hidrobo and Shalini Roy are Research Fellows with IFPRI’s Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division. This post first appeared on VoxDev. The studies were carried out by researchers at IFPRI in collaboration with researchers from Cornell University, University of Washington, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the UNICEF Office of Research—Innocenti. This work was undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM) led by IFPRI.

1. Note: Outcome variable is the adjusted mean prevalence of any physical and/or sexual violence in the last six months, calculated from the marginal effects of probit models. Standard errors are clustered at the cluster level. Basic controls include baseline prevalence of physical violence and dummy for province stratum. (N=1,226).

2. Note: Outcome variable is the adjusted mean prevalence of any physical violence in the last six months, calculated from the marginal effects of probit models. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering. Extended controls include baseline characteristics of woman and husband. (N=2,231).

3. Note: Outcome variable is the adjusted mean prevalence of physical violence in the last 12 months. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering. Extended controls include baseline characteristics of woman and husband. (N=1,261).