“It’s through the show that you understand what’s going on in the world. For teenagers, it’s by watching the show that they will understand the problems of a 15-year-old girl who is married and pregnant. You can always talk to them, but by watching the show, the images, they will realize that it’s real and they will be careful. Even women who don’t have children yet, like me, will understand how childbirth happens and will take lessons for tomorrow” ~ Married woman in Kolda

Everyone loves a good TV show—one that captivates, elicits strong emotions, makes you reflect on your life and leaves you wanting more. Using the power of media to educate is the hallmark of the “edutainment for development” approach—embedding diverse behavior change messages in drama reaching key audiences via TV, radio, and social media. Social scientists have increasingly studied how edutainment can be used to improve gender and health-related outcomes in Africa, including programming to change HIV and risky sex in Nigeria, early and forced marriage in Tanzania, and violence against women in Egypt. Understanding if edutainment is effective, through what mechanisms, and among which populations, can help improve overall development outcomes—while contributing to viewers’ enjoyment and quality of life.

In 2019 we embarked on a mixed-methods evaluation of a popular West African television series C’est la Vie! designed around gender and women’s health and rights themes. The show revolves around everyday life in a maternal health clinic in Senegal and is developed and produced by the Senegalese NGO Réseau Africain pour l’Education à la Santé (RAES, African Network of Health Education). The study investigated whether viewing the show improved adolescent girls’ and young women’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors with respect to violence against women and girls (VAWG), and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) in rural areas. In this post, we summarize takeaway findings, challenges, and where the research agenda on gender and edutainment is headed next.

PROMO REEL – C’est la vie! – Saison 1 from Keewu Production

Study design and COVID-19 adaptations

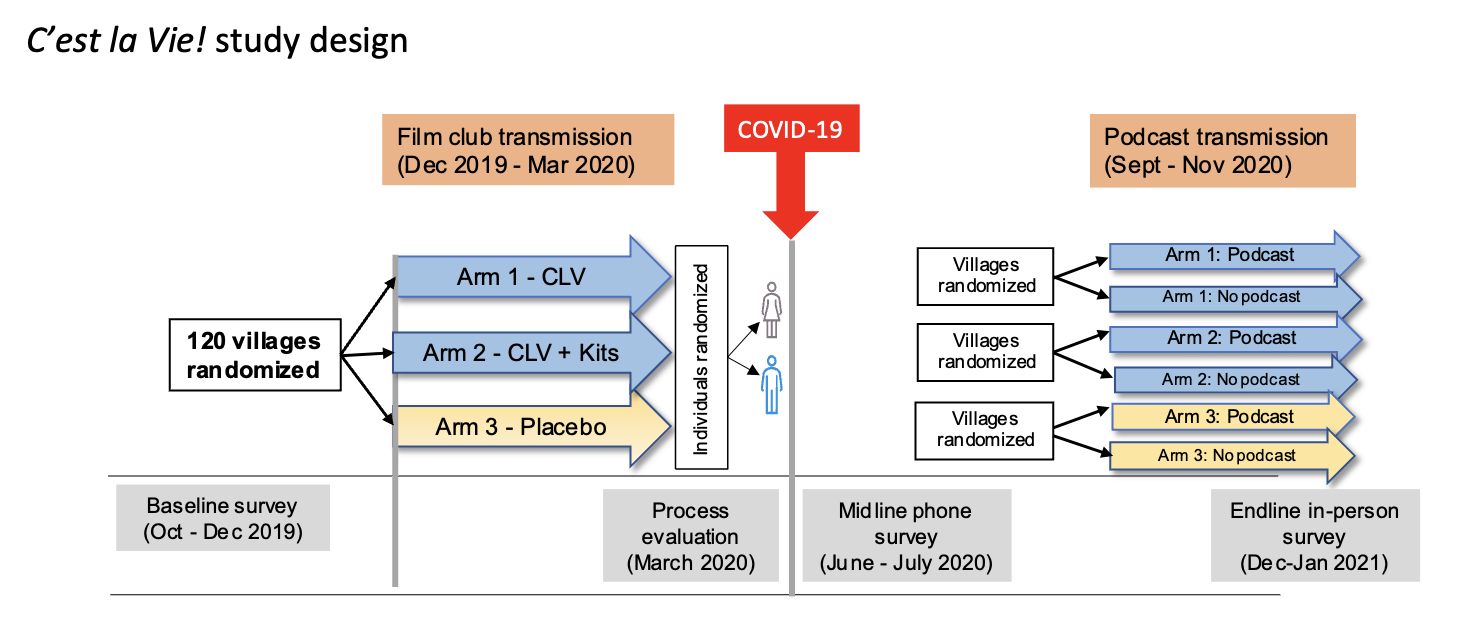

In a randomized control trial, 120 villages across two regions of Senegal (Kaolack and Kolda) were randomly assigned to receive either 1) Season 1 of C’est la Vie! screened via film clubs (CLV), 2) same as arm 1 plus pedagogical kits that included post-screening discussions and workshops (CLV+kits); and 3) a placebo series, Golden, screened similarly as arm 1 (Control).

Film clubs, organized by the NGO MobiCiné, consisted of biweekly group sessions of approximately 75 minutes, allowing for three episodes to be screened in one sitting. Adolescent girls and young women aged 14-34 were invited to attend the screenings and allowed to bring a guest; a randomly assigned “soft nudge” encouraged participants to bring either a male or female guest in order to explicitly test how involving men and boys might change outcomes.

The baseline survey for the study was conducted in late 2019, with the film clubs starting in December 2019 (Figure 1). To capture implementation quality and adherence to the study design, we implemented a process evaluation at the beginning of March 2020. On March 23, the government of Senegal declared a state of emergency due to COVID-19, forcing the closure of the film clubs halfway through implementation (approximately 4.5 out of nine planned sessions had taken place). We implemented a midline phone survey (three months post-film clubs) to capture C’est la Vie!’s short-term impacts. In an effort to continue to reach women with thematic content during periods of social distancing, we shifted delivery of C’est la Vie! to audio podcasts broadcasted via mobile phone. To ensure we could still learn from the shift to podcasts, we randomized 60% of villages within each treatment arm to receive the podcast (while for the remaining 40%, the intervention effectively ended at the start of the pandemic). Finally, we implemented an in-person endline survey approximately nine months after the film clubs had ended, or approximately one year after the baseline survey.

Figure 1

Source: IFPRI

Main takeaways: Implementation and impacts

- Film clubs were a huge hit, with high take up and attendance: Overall, nearly 90% of target (invited) girls and women participated in film clubs—attending on average 64% of screenings. Participants overwhelmingly reported loving C’est la Vie! and did not want the film clubs to end. They learned new things, were “awakened” to life outside their communities, and discussed what they learned and saw with family and friends. In a complementary process evaluation, we further assess implementation (intervention adaptations and fidelity), as well as participants’ responsiveness and engagement, and series appropriateness for the target population, with the overall conclusion that edutainment is a promising approach to reach and engage rural conservative populations.

- There were promising short- and medium-term impacts on knowledge and attitudes—but few impacts on behaviors: In the short term, approximately three months after film club activities had stopped, we found encouraging impacts on VAWG and SRH knowledge. Impacts on VAWG knowledge aggregates are large (0.281 standard deviations [SDs]), driven by increases in knowledge of adverse consequences of child marriage, female genital mutilation (FGM), and intimate partner violence (IPV). Impacts on SRH knowledge are smaller but significant at 0.174 SDs, driven by knowledge of modern contraceptives and HIV transmission and prevention methods. In the medium term, nine months after film clubs ended, these knowledge impacts have faded out. However, we find significant improvements in attitudes and norms with respect to GBV (of 0.128 SDs) in the medium term, driven by the same themes, in addition to norms rejecting sexual violence. While we see significant improvements in one individual indicator of VAWG behaviors—rates of FGM among daughters of the target group—overall aggregate impacts on behaviors across VAWG and SRH are null. These findings point to the importance of measuring the evolution of impacts over time, as well as the challenges in changing behaviors.

“The film club changed women’s outlook on child marriage because I once heard my wife say that the minimum age to give our daughter into marriage is 18 and [now] she goes further by saying that she will not give our daughter in marriage until 20 years and I am in tune with her and ready to support her in her vision” ~ Male FGD participant, Kaolack

- Adding pedagogical kits resulted in little additional impact: Across outcomes and survey waves, we find few significant differences due to the addition of the pedagogical kit, possibly because participants were already widely discussing themes and the content of the series outside the film clubs, or because the kits did not introduce significantly more information than was already transmitted in the series. In addition, the content and breadth of the kits were condensed to adapt to implementation challenges in rural areas—thus it is possible that impacts would have been larger with more intense or in-depth implementation of the kits.

- Involving men and boys is linked to potential gains in SRH but not VAWG: We find that SRH knowledge gains were up to twice as large in the male nudge group than in the female nudge group—however, we find no other differential impacts. Thus, despite the effort to include men and boys through guest invitations, it was not enough to change most outcomes. The process evaluation reveals that participants believed film clubs were “for women” and the series focused on “women’s issues.” Even when men and boys attended, they were a minority and unlikely to return for future sessions. These results suggest that more effort to engage men and boys, including content focused on men and boys, may be needed to move the needle on broader behavior change.

- Extending the intervention through COVID-19 via podcasts was unsuccessful: Despite efforts to pivot implementation during the pandemic, podcasts faced implementation challenges, with lower participation rates than film clubs, possibly because of access and connectivity. In addition, it is possible the podcasts were simply less entertaining than gathering with friends and family to watch the series on a big screen. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we found no additional impacts from the podcast extension across knowledge, attitudes or behavior outcomes—signaling the challenges in remote administration of edutainment, and the role of engagement and community interactions to promote impacts.

“Cinema solves many disputes in the community. The women have become more and more friends because of the film club. I’ve never been in a good relationship with the one sitting next to me. But thanks to the cinema, we have become friends” ~ Female FGD participant, Kolda

- “Transporting” viewers was important for impacts: We find that adolescent girls and women who were more “transported” (emotionally moved) by the series had significantly larger impacts compared to those who were less transported, suggesting that the power of edutainment lies in its ability to emotionally engage viewers in the storyline. This highlights the importance of the production phase in generating content that will absorb and captivate viewers.

While our trial showed mixed success, impacts in the short- and medium-term on VAWG knowledge and attitudes show the potential for broader behavior change. Impacts are promising. given that only half the intended content was delivered due to the pandemic. Moreover, the C’est la Vie! series diverged from forms of edutainment evaluated in other studies, as it tackled a wide range of themes. Thus, content on any one issue was less directive and intensive than would be expected from a single thematic series. With technological advances, the potential of edutainment for development is gaining momentum. We hope to see more on how: a) researchers can work hand-in-hand with the creative community to produce content aligned with the evidence frontier, b) diverse platforms and linkages to services can be leveraged to deliver and bolster edutainment and c) how content for gender issues can involve and target men to move the needle on violence, masculinities and more. Stay tuned!

The C’est la Vie! impact evaluation study team includes: Malick Dione (IFPRI Dakar), Jessica Heckert and Melissa Hidrobo (IFPRI), Agnes Le Port (IRD), Amber Peterman (UNC) and Moustapha Seye (LARTES, University of Cheikh Anta Diop).

The team would like to thank implementing partners, MobiCiné and the Réseau African pour l’Education à la Santé (RAES) for helpful comments and for collaboration on this research. We thank research partners, including the hard-working field teams of ASSMOR Consulting (baseline and endline) and Laboratoire de Recherche sur les Transformations Economiques et Sociales (LARTES) (midline) and the adolescent girls and women who took part in our survey and shared their stories for this analysis. Finally, we are thankful to the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM) and an anonymous donor for funding this work.