The World Food Prize Foundation 2022 Borlaug Dialogue, with the theme “Feeding a Fragile World,” focused on how to deal with the shocks to global food systems caused by the now-infamous “Triple C”: COVID, Conflict, and Climate. To showcase cutting-edge research and innovation that is contributing to the global response to these challenges, CGIAR hosted a side event on “Multiple-Win Solutions to the Global Food Crisis.”

The Oct. 19 discussion focused on both rapid responses to the food crisis and longer-term solutions for climate resilience and inclusive and sustainable food systems, highlighting the crucial role that CGIAR and partners play in this effort.

“The confluence of current challenges to food security make it clear that our food systems are not fit for purpose, not if that purpose is to deliver affordable and healthy diets for all people, while at the same time safeguarding natural resources and mitigating the environmental footprint of agrifood systems,” said Marco Ferroni, CGIAR System Board Chair, in his opening remarks.

The notion of multiple-win solutions, he explained, arises from systems thinking that recognizes interdependence of critical components of agrifood systems and prioritizes intervention strategies that avoid the unintended consequences of siloed approaches.

David Nabarro, 2018 World Food Prize Co-Laureate, in a video message to the participants, shared similar sentiments in his overview of the UN Global Crisis Response Group, which he co-leads. “The increasing number of conflicts we’ve seen in recent years has compounded the effects of climate change and COVID-19. Taken together, COVID-19, climate change, and conflict signaled to many national leaders that things weren’t well with our food systems. This just got worse with the war in Ukraine,” Nabarro said. While social protection interventions and humanitarian assistance are required immediately, he added, we also must work to build longer-term resilience by ensuring farmers can obtain needed seeds and fertilizer—and for that, households and governments need greater access to cash.

Johan Swinnen, CGIAR Managing Director, Systems Transformation and IFPRI Director General, thanked Nabarro for his outstanding leadership and reiterated the idea that “volatility is the new normal,” requiring a much greater focus on making food systems more resilient to shocks. The broad spectrum of problems we are facing now requires a systems response, Swinnen said, and CGIAR, a global research organization which has resilience and systems approach written into its 2030 Research and Innovation Strategy, is well suited for the purpose.

Swinnen outlined CGIAR’s response to the current food crisis, grouped around seven innovation areas (Figure 1). From real-time monitoring and early warning systems to soil fertility solutions, he noted, there is much room for improvement. How do we re-think our approaches to food and nutrition security in inherently fragile settings? How can we address soil fertility without relying on the traditional fertilizers in the context of recurrent market and value chain disruptions? And how do we make sure the most vulnerable populations are not left behind?

Figure 1

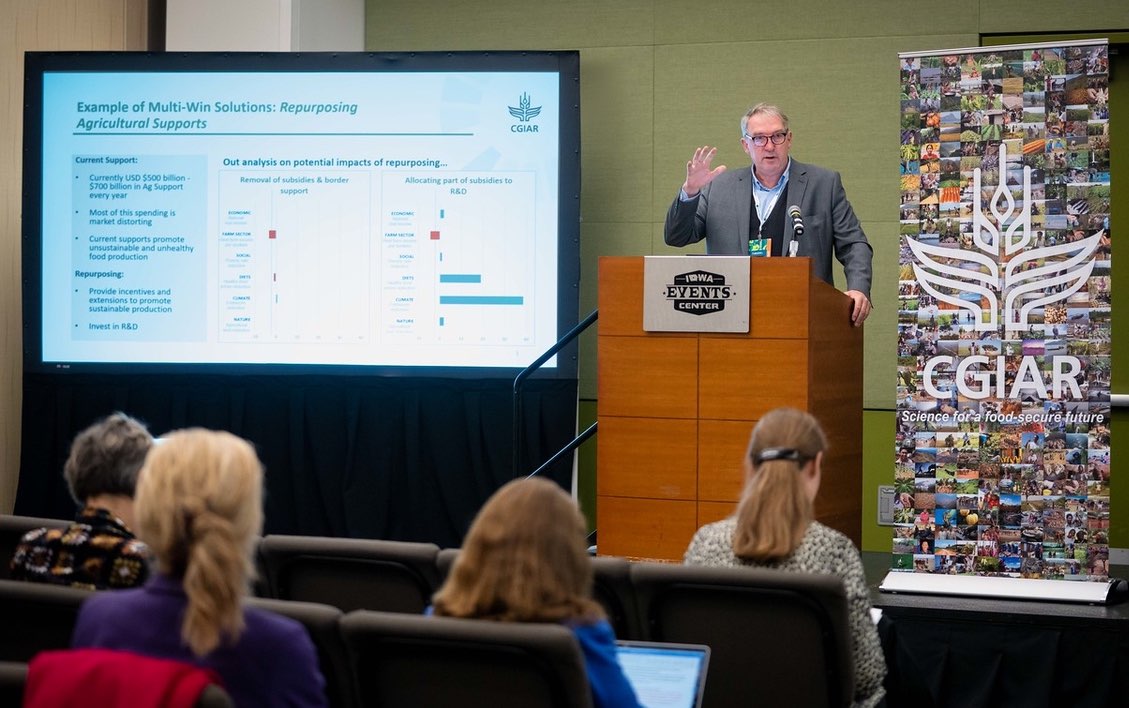

Swinnen shared several examples of multi-win solutions CGIAR and partners have been working on to answer those questions. An analysis produced in collaboration with the World Bank and FAO provides a starting point for rethinking the architecture of food and agriculture finance. Currently, governments around the world spend up to $700 billion every year in agricultural support, said Swinnen, yet not only does most of this spending distort markets, it does not support sustainable and healthy food production.

The analysis shows that repurposing part of these subsidies into incentives to promote sustainable production and agricultural R&D would bring about significant improvements in diets (by increasing the affordability of healthy food), climate and ecosystems (through reduced emissions and less extensive crop production), as well as improve national real incomes and reduce poverty rates. Multi-win solutions for soil health include sustainable intensification technologies and practices that can reduce yield gaps while avoiding dangerous cropland expansion and other negative environmental impacts. Gender-sensitive policies and interventions not only promote equality and social inclusion but also help reach groups (women and youth) most vulnerable to food systems shocks.

A panel discussion further explored questions of integrated approaches, innovation, and scaling.

Dina Esposito, Global Food Crisis Coordinator and Lead, Bureau for Resilience and Food Security at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), noted that CGIAR has been an important strategic partner to USAID in this global food crisis. “The CGIAR innovation areas very much align with our Global Food Security strategy, which is also taking a systems approach,” said Esposito. “The response to the current global food crisis cannot simply be on the humanitarian side,” she added, stressing that development resources and interventions remain critical. USAID continues to rely heavily on CGIAR research, particularly on how food, fuel, and fertilizer prices are affecting USAID programming in its priority countries. CGIAR modeling work on impacts of different policy actions, as well as early warning systems, help USAID prioritize resource allocation and analyze current and projected future impacts of interventions, said Esposito.

Mahalingam Govindaraj, this year’s recipient of the 2022 Norman E. Borlaug Award for Field Research and Application and Senior Scientist for Crop Development at HarvestPlus and the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, shared his perspective on how biofortification and other technologies can promote nutrition during times of crisis. He stressed the importance of promoting the use of biofortified crops systematically. This includes partnering with farmers and private sector actors to help them understand the value of this approach, and with the public sector in creating an enabling environment for scaling up innovations. “Climate change and nutrition are two sides of the coin, as we need to improve both stress resilience and nutrition stability [of crops] to benefit more farmers and consumers,” said Govindaraj.

Jan Low, Principal Scientist at the International Potato Center (CIP) outlined how nutrition and crop breeding programs can support longer-term development goals in times of crisis. “Disaster response with proper planning can be a development opportunity,” said the 2016 World Food Prize Co-Laureate. To seize this opportunity, though, researchers need to plan breeding programs ahead of time, align them with areas that are most vulnerable to shocks, and run preparatory research in those areas to understand how local seed systems work and who the key players are. Breeding takes time, and such preparations can help ensure that suitable and quality planting material is ready when it’s most needed and that emergency interventions like free grain distribution don’t undermine existent commercial seed systems, Low concluded.

Wrapping up the discussion, Ferroni listed several key elements of the “big tent” the international research and development community must build to address the current and future crises: Inclusive innovation, systems thinking, partnerships, bundling of contributions, scaling, adoption enabling services, policy, and institutional changes. “We can all agree that we can neither afford to lose nature in the quest to feed people, nor the many opportunities to improve livelihoods, incomes, and diets in a reimagined approach to agrifood systems renewal and innovation,” concluded Ferroni.

Evgeniya Anisimova is IFPRI’s Acting Media and Digital Engagement Manager. This post also appears on the CGIAR website.