Daku Bai Gayatri lives in the village of Rawaliya Khurd Panchayat in Udaipur, Rajasthan state, India. She reports that residents there face water shortages every summer. Despite groundwater depletion, community members believe that every farmer requires a borewell. Gayatri sees the need for rules over groundwater extraction and ponders how they can be put in place.

Shuklambara Pradhan lives in Angapada Panchayat in Angul District, Odisha state. In Angapada, farmers who have fields downstream of a channel only receive water for irrigation if those upstream allow it to flow. Pradhan believes that without coordination between upstream and downstream farmers, the latter group will face water shortages—leading to conflicts. (Hear their original voices here).

Both touch upon the core issue facing water resources in India and globally: The lack of mechanisms for effective governance. The issues they highlight are widespread in India. Nearly half of all wells show falling water tables, and current trends of over-extraction will put at least 25% of agricultural production at risk within 20 years. While the need for effective groundwater governance is well established; how best to achieve that goal is not—particularly on the scale necessary to address widespread depletion of fresh water resources.

Daku and Shuklambara are two out of more than 500.000 participants from more than 4,500 villages who participated in interventions of the project Experimental Games for Strengthening Collective Action.

Project team members from IFPRI, the Foundation for Ecological Security, and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) explored the potential of experimental games to catalyze community-driven processes to trigger collective behavioral and institutional change for improving groundwater governance. The project used experiential learning through games in combination with debriefings and participatory water planning tools. Emerging evidence supports this approach to address the management of shared water resources as “commons.” Commons management merits greater attention and investment in research and pilot implementation.

As games gain increasing attention as an intervention tool, there is a danger of designing game-based interventions on the basis of simple and unclear assumptions about human behavior. To address this concern, we 1) conceptualize how games can influence behavior related to commons management; 2) identify design elements that best support this process; and 3) reflect on game intervention cases, focusing on experiential learning games, which have the explicit intention to address social dilemmas around commons management.

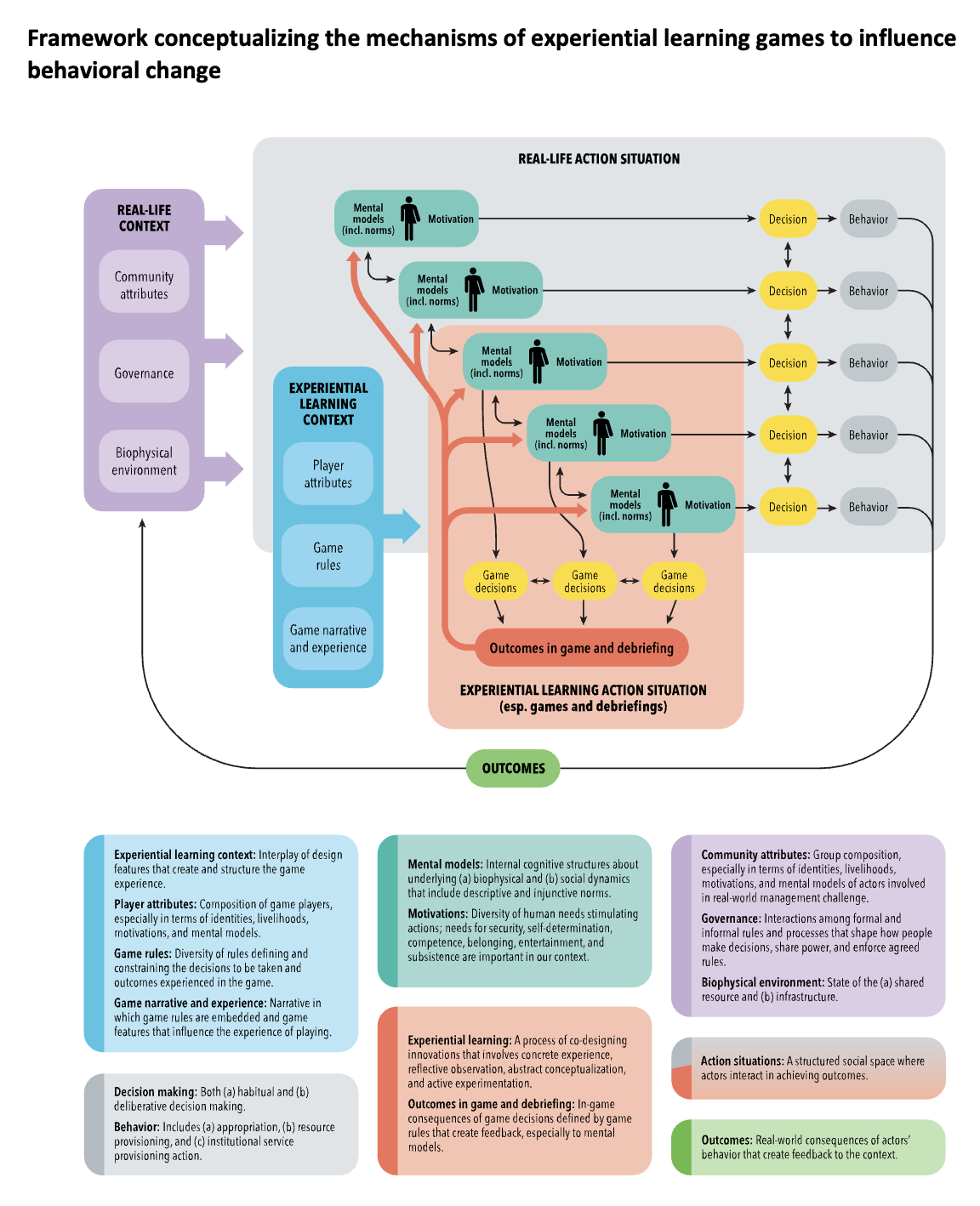

Figure 1 summarizes our conceptual thinking. The framework is inspired by the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework (Ostrom 2011), which helps clarify the understanding of complex collective action problems. We integrate lessons from psychology, economics, and behavioral and education science related to individual and collective learning and behavior. Our focus is on action situations, which are structured social spaces where actors learn, make decisions, and interact to achieve outcomes. Our framework distinguishes between the real-life action situation (RLAS, grey box) and the experiential learning action situation (ELAS, apricot box). The RLAS can be any social-ecological interaction and is embedded in a broader real-life context (purple box). The ELAS is built around games but also includes debriefings in which game players and other community members share their experiences and discuss connections to their real life challenges. An overlap exists between the actors present in the ELAS and the RLAS. Our underlying assumption is that experiences in the ELAS influence behavioral determinants, which then affect actors’ behavior in the RLAS (for more details please see Falk et al. 2023).

Figure 1

Source: Falk et al., 2023

To make this more tangible, here’s how one game worked. The most widely-used, the groundwater game, addresses the critical issue of groundwater overexploitation in India. In each participating community, there was one game session with a group of five men and another with a group of five women. Each group began with a certain groundwater level. In each game round, players were asked to choose between a more profitable but more water-intensive crop and a less profitable but more water-efficient crop. A fixed water recharge amount was given after each round. If too many players chose the water-intensive crop, water use would exceed recharge and the groundwater level fell. If the water table went below a threshold, the game was over. The game had a phase without communication and a phase allowing it.

The game was first piloted in 17 communities in rural Andhra Pradesh, where it was conducted twice in the same communities in 2013 and 2014, and compared to nine control communities (Meinzen-Dick et al. 2016). Respondents in treated communities were significantly less likely than those in control communities to report the widespread belief that crop choices were individual decisions and in principle should not be restricted in any way. Treated communities more frequently expressed the need for farmers to cooperate and were also more likely to have introduced water registers or groundwater management-related rules compared to control sites (Meinzen-Dick et al. 2018).

Based on these experiences, we have scaled up this approach: As of November 2023, over 4,500 rural communities in six Indian states have participated in experiential learning interventions that included 1) collective action games that allow people to experience effects of their water use decisions on water management and try out different rules; 2) structured community debriefings to discuss the implications of the games; and 3) crop water budgeting to facilitate participatory water planning. To be able to scale such interventions, we simplified the approach so they could be used by community-based facilitators.

The promising results of our interventions generated interest among government, civil society, and private sector actors. Atal Bhujal Yojana (ABY), the Indian government’s flagship program aimed at strengthening the participatory management of groundwater, has started using the experiential learning tools to aid communities. Around 500 Atal Bhujal staff have already been trained for this initiative. In addition, the Odisha Department of Agriculture & Farmers’ Empowerment and Odisha Livelihood Mission have been using these tools in their sustainable agriculture initiative through field level functionaries called Krishi Mitras. They join several other NGOs and organizations that are using the tools in their engagement with the communities.

Commenting on the situations in their villages, Pradhan and Gayatri emphasized the importance of establishing coordination mechanisms among resource users, and more broadly, collective action around water resources. The villages that participated in our sessions show several promising outcomes. First and foremost, the interventions initiated constructive conversations within communities regarding the pressing water challenges, where previously these issues were seldom discussed. In some areas, the community passed resolutions to check water availability before making the winter crop choice. In other villages, the practice of sharing borewells has become a norm. The games do not change things overnight, but they create a basis for interest and action to address pressing resource management challenges.

Thomas Falk is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Natural Resources and Resilience (NRR) Unit; Richu Sanil is a Senior Project Manager with the Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), Ruth Meinzen Dick is an NRR Senior Research Fellow; Pratiti Priyadarshini is an FES Senior Program Manager.

The project on Experimental Games for Strengthening Collective Action? Learning from Field Experiments in India is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) commissioned and administered through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Fund for International Agricultural Research (FIA).