Tajikistan’s agricultural sector is uniquely shaped by the country’s history and geography.

When Tajikistan was part of the former Soviet Union, farming was collectivized. But soon after gaining its independence in 1991, the country embarked on a set of reforms intended to de-collectivize agriculture. Over 90% of this landlocked country is mountainous, leaving relatively little room for agricultural land. Yet the agricultural sector is Tajikistan’s largest employer. Efforts to develop the sector have often focused on predominantly rural Khatlon Province, historically the country’s poorest region.

More than 30 years after the post-Soviet reforms, Tajikistan’s agricultural landscape continues to evolve as a result of changes in markets and value chains, economic development projects, and efforts by farmers and farming communities. How are these changes affecting Khatlon’s farming households—specifically, their agricultural production?

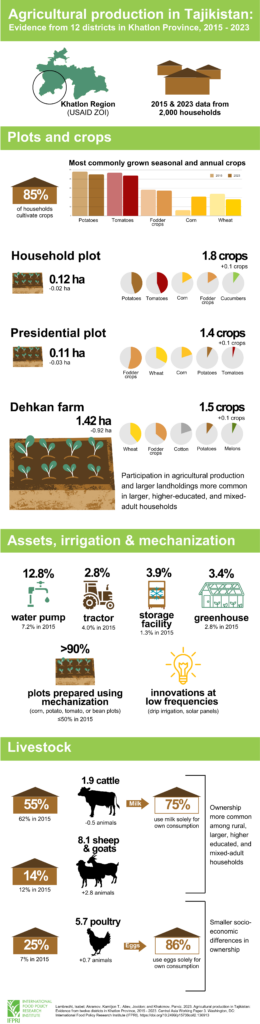

To investigate this question, we surveyed 2,000 households in 12 districts of Khatlon—the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Zone of Influence—in February-March 2023, with results presented in a recent Working Paper. Most of the respondents had been previously interviewed in February-March 2015, offering a good opportunity to detect changes in agricultural production over this period.

Plots and crops

Most households (85%) in our survey area are cultivating crops, typically on very small-sized plots. Three plot types are common in Khatlon: Household plots are typically small parcels of land that lie adjacent to a house. Presidential plots are lands distributed under two presidential decrees (in 1995 and 1997) to increase households’ food production for their own consumption. Dehkan farms were formerly part of state-owned collectives during Soviet period, then redistributed to farm workers when the collective farms were dismantled. They are also, on average, over 10 times larger than the other two plot types. Most households (94%) own household plots, while 24% own presidential plots, and 10% dehkan farms.

Average farm and plot sizes decreased between 2015 and 2023. This is likely due to an increase in the absolute number of farm households as well as further breakup of dehkan farms in the study area. Indeed, the greatest change is seen among dehkan farms, whose average size shrank by 40% in this period.

In contrast, on-farm crop diversity increased, with a major shift in cropping patterns from 2015-2023. While fewer households grew potatoes, tomatoes, wheat, and onions, more households cultivated maize, corn, cucumbers, beans, and peppers in 2023 than eight years before. The largest variety of crop cultivation is seen in household plots. As the harvests from these plots are often used for the household’s own consumption, this increased crop diversity may hopefully lead to improved household dietary diversity—a notable issue in Khatlon. Additionally, increased crop diversity are likely contributing to improved climate resilience, higher incomes, and improved food security.

Cotton—nicknamed Central Asia’s “white gold” despite often delivering little profit to farmers—continues to be prominent in Khatlon’s landscape. It was grown on about a third of all dehkan farms in both 2015 and 2023. Nevertheless, in line with the reduction in plot sizes of dehkan farms, the average parcel area on which cotton is grown decreased by over a third (from 2.31 hectares in 2015 to 1.47 ha in 2023). This steep drop hints at a decline in the total area of cotton being cultivated in the study region, consistent with reports from other sources.

This change in agricultural landscape coincides with a nationwide expansion in the area dedicated to horticulture crops (vegetables and fruits) as documented by the National Academy of Sciences of Tajikistan, particularly in Khatlon.

From 2005 to 2022, horticulture crop area in Khatlon increased 2.7-fold compared to a 1.7-fold average increase in the rest of the country. Despite this, horticulture crops accounted for only 20% of annual and perennial crops in Khatlon in 2022, the lowest share nationally, with other regions averaging 27%. The above-average expansion of the area in Khatlon dedicated to horticulture crops also ceased around 2015, thereafter following the country’s average trend. Thus, grains and cotton remain the major crops in Khatlon, and, as seen in our study, are among most commonly grown crops on presidential plots and dehkan farms (graphic).

Infrastructure and machinery

Small farm sizes and low ownership rates of agricultural machinery have not impeded households from mechanizing their farming activities. By 2023, mechanization was used for land preparation for nearly all major crops, up from much lower levels in 2015. Mechanization is also increasingly being used for harvesting, though rates remain low. The expansion of machine rental services, which respondents said are readily available, helps to make up for generally low household ownership of farm machinery.

More households have water pumps and more plots have irrigation in 2023 than in 2015; a similar trend holds for greenhouse and storage facilities (particularly cold storage). Agricultural innovations including drip irrigation and solar panels have also emerged in the region but are still implemented at very low levels (<1%). No significant change is seen in the share of households that utilize mineral fertilizer, around 72% in 2015 and 74% in 2023.

Livestock

As with cropping patterns, significant changes have occurred in livestock ownership from 2015 to 2023, with potentially direct implications on household food intake. For one, fewer households own cattle and the households that have cattle own fewer animals. With three out of four households that produce milk solely using this milk for their own consumption, the significant decrease in dairy cows (from 40% in 2015 to 33% in 2023) may explain why fewer women consume milk in 2023 than eight years prior.

In contrast, the share of households that own poultry has more than tripled, from 7% in 2015 to 25% in 2023. Of the households that have chickens, 86% use the eggs only for their own consumption. This increase in poultry ownership is paralleled with an increase in the proportion of individuals consuming eggs in the household.

Slightly more households own sheep and goats in 2023 than did in 2015 (14% vs. 12%). A larger change is seen in the average heard size, increasing by nearly three animals to households owning an average of eight sheep and/or goats in 2023.

Looking ahead

Continuing developments in agriculture are likely to have significant impacts on the livelihoods of many Tajikistan residents; off-farm income-generating opportunities are scarce and many communities are remotely located and at times isolated (e.g., during heavy snowfalls in winter). Thus, the observed increase in crop diversity between 2015 and 2023 as well as emerging innovations along the agricultural value chain are favorable developments. These changes are particularly promising for nutrition, as agricultural (crop and livestock) diversity has been linked to better diets and improved food security outcomes. Continued low levels of diet diversity during winter, though, suggests further development efforts are needed.

Isabel Lambrecht is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance (DSG) Unit, based in Dushanbe, Tajikistan; Sarah Pechtl is an IFPRI Non-Staff Fellow and Mickey Leland International Hunger Fellow in Dushanbe; Kamiljon Akramov is a DSG Senior Research Fellow; Jovidon Aliev is a DSG Senior Research Analyst in Dushanbe; Parviz Khakimov is a DSG Senior Research Fellow and Tajikistan Country Program Leader.This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed.

Referenced Working Paper:

Lambrecht, Isabel; Akramov, Kamiljon T.; Aliev, Jovidon; and Khakimov, Parviz. 2023. Agricultural production in Tajikistan: Evidence from twelve districts in Khatlon Province, 2015 – 2023. Central Asia Working Paper 3. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.136913

Funding for this work was provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

through the Tajikistan Evaluation and Analysis Activity.