Over-extraction of groundwater is a prominent challenge in India, which withdraws more of this key resource each year than the United States and China combined. At least one-third of India’s districts have problems with groundwater overexploitation or contamination. This has profound implications for food security, livelihoods, and economic development. As groundwater is an “invisible” and mobile common pool resource, sustainable governance is complex and multifaceted, requiring coordination among various stakeholders at different scales. Results of attempts around the world indicate that neither communities, nor markets, nor governments alone have been effective in ensuring sustainable groundwater management.

In this context, what can be done to strengthen groundwater governance on a large scale? We argue that this requires systemic changes. Systems are understood as patterns of behavior and interactions of actors in an ecological, social, political, economic, technical, and cultural context maintaining or creating changes (inspired by McGinnis and Ostrom 2014 and Woltering et al., 2019). Changing the system requires understanding the behaviors of actors in the system network, as well as the institutions that shape the direction in which the system moves. This understanding can then be applied to select the right approaches to influence behavior and the overall system.

The Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), together with other NGOs, government partners, and academic and research institutions including IFPRI and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), are applying this behavioral system perspective to support sustainable natural resource governance in India.

FES’s work illustrates how systems thinking can inform multi-methods approaches based on the concept that diverse actors’ interlinked behavioral changes can bring about large-scale improvements in sustainable groundwater management. By applying this systemic behavioral perspective, FES and partners work at multiple scales (from local to national) with different actors engaging with different resource systems. In this process key questions are repeatedly asked: Which actors need a behavioral shift and which strategies will affect their behavior? How can they be motivated or enabled to change their behavior toward sustainable resource management?

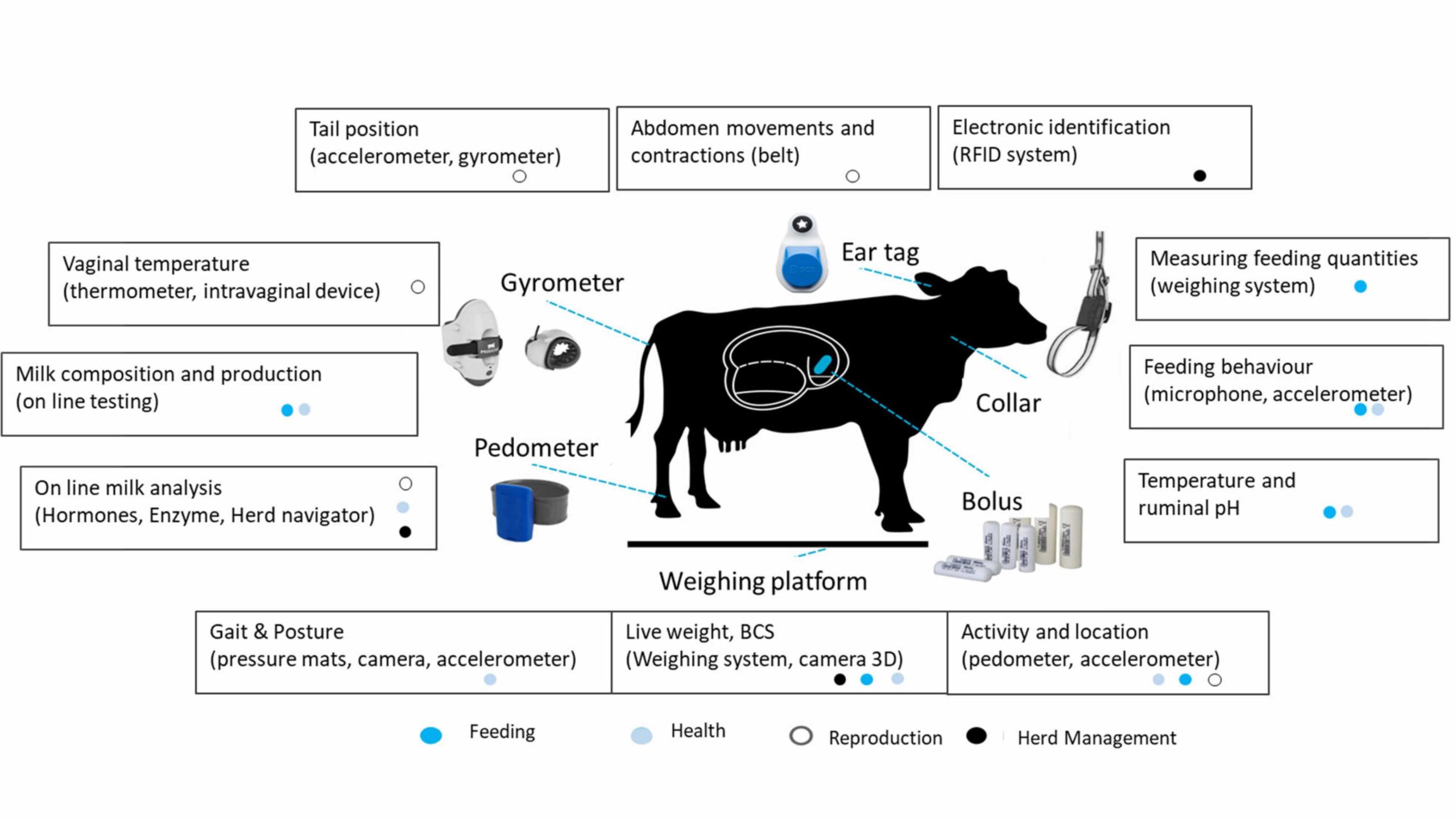

FES, IFPRI, and ICRISAT co-designed and use a combination of demand and supply side interventions at the community level while simultaneously engaging with actors at higher-level decision-making. Figure 1 illustrates how actors and institutions interact and are influenced by various tools and approaches.

Figure 1

An important aspect of FES’s strategy is the acknowledgment of how interwoven the behavior of the various actors is. Different interventions target different actors, and there are diverse intermediary outcomes that eventually lead to a change in water management. The arrows illustrate the interconnections between actors and interventions, which are not isolated but create a web of influences.

A multipronged approach to behavioral change

The FES-led efforts started with participatory groundwater monitoring, involving community members in measuring water levels in wells and uploading the data to an open-access web platform that combines hydrological information to promote the visibility of the resource. In addition, groundwater games were used as structured, replicable approaches to acquir knowledge and influence behavior by experiencing, reflecting, and experimenting. The games simulate farmers’ choices between water-intensive and water-efficient crops: If everyone uses groundwater for water-consumptive crops to increase their short-term incomes, water tables fall, threatening the long-term viability of the groundwater system. The games are followed by a debriefing session where all members of the village are invited to discuss the game, connect it to their real-life water management challenges, and create space to co-develop ideas for improving the situation.

These two exercises—helping participants become aware of water scarcity and the game experience showing how individual actions affect the resource and other community members—are the foundation for using participatory planning tools such as Crop Water Budgeting (CWB). CWB helps communities estimate their annual water availability and collectively make decisions on cropping patterns that fit with the available water.

In addition, the Composite Landscape Assessment and Restoration tool (CLART) provides a geographic information system (GIS)-based Android tool to assist community leaders or local government officials to plan soil and water conservation measures based on their local conditions, to help recharge groundwater or increase surface water availability.

An important additional aspect of the strategy was training community members (Community Resource Persons) to facilitate each of these approaches—games, debriefings, CWB and CLART. Combining all these efforts can strengthen norms, activate intrinsic motivations for sustainable and fair water management, and eventually change individual and collective resource use behavior.

Ways to support wider collaboration

Nevertheless, leaving system change to uncoordinated local actions would be risky and inefficient. Therefore, supporting collaboration among actors is another critical mechanism to systemically improve water governance and management. The concerted interventions at the community level, the support of cooperation and collaboration across communities, and influencing actors at higher levels of governance make sustainable water management more likely.

This kind of collaboration depends on participants better understanding each other’s interests and perspectives. The project—particularly in the use of multi-actor platforms, and as coalitions are built—can potentially create a sense of common goals, helping individual participants align each other’s actions. Multi-actor platforms also aim to mobilize strategic resources, while coalition-building encourages participants to enable larger-scale change by influencing policies and programs. Participants also complemented those efforts by working to develop the capacity of government, civil society and private actors to accelerate the application of sustainable water management approaches at large scale.

This approach helps to clarify specific assumptions about why actors behave the way they do. Identifying what drives their behaviors is key for developing powerful intervention strategies and to understand the pathways to influence changes in the wider system. FES’s combination of approaches is the result of this assessment. More information about this work can be found in our paper.

Thomas Falk is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Natural Resources and Resilience (NRR) Unit; Richu Sanil is a Senior Project Manager with the Foundation for Ecological Security (FES); Ruth Meinzen-Dick is an NRR Senior Research Fellow. Opinions are the authors’.

Note: This work was conducted under the project on Scaling up experiential learning tools for sustainable water governance in India, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) commissioned and administered through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Fund for International Agricultural Research (FIA). It was implemented by the Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). The study also received support from the CGIAR NEXUS Gains Initiative.

Referenced paper:

Sanil, Richu; Falk, Thomas; Meinzen-Dick, Ruth S.; and Priyadarshini, Pratiti. 2024. Combining approaches for systemic behaviour change in groundwater governance. International Journal of the Commons 18(1): 411–424. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijc.1317