Some governments have responded to alarms about possible COVID-19-related food shortages much as consumers would: By trying to hoard food. A number of countries have limited exports of key staple food commodities to protect domestic supplies. Timothy Sulser and Shahnila Dunston assess the possible impacts of such export constraints for the two most affected markets, rice and wheat. They conclude that international rice markets are particularly sensitive to such restrictions by large exporters—modeling shows they could significantly boost global prices and push millions of poor rice consumers into hunger.—Johan Swinnen, series co-editor and IFPRI Director General.

Imposing trade restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic can have dramatic adverse impacts on food security, as Glauber et al. (link), Balié and Valera (link), and Laborde et al. (link) have suggested. And, while the crisis will likely impact food security through other significant channels, such as the effects on incomes (link), understanding the potential food price and hunger impacts specifically from trade bans demonstrates how harmful these policies can be to efforts to withstand this shock. To better understand these specific impacts, we use IFPRI’s IMPACT model (link) to simulate the potential effects of such measures in markets for wheat and rice—the two crops attracting most trade restrictions at the moment.

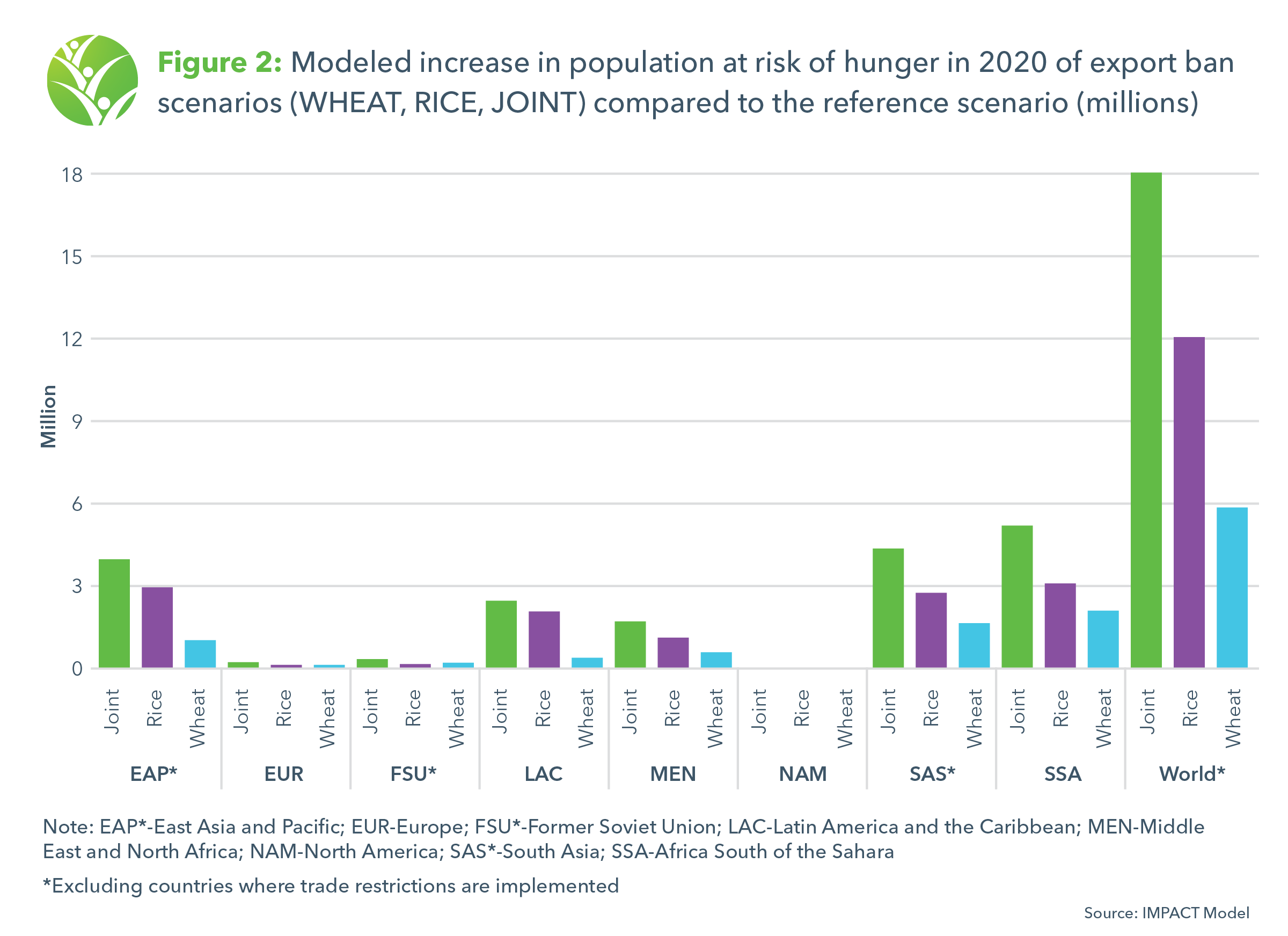

The modeling suggests that prices could rise significantly due to such export bans and, with these actions in the rice and wheat markets alone, as many as 18 million more people worldwide could face chronic hunger in 2020 as a result.

We explore four alternative scenarios: A reference case before COVID-19-related restrictions, one scenario each reflecting rice and wheat export bans in selected countries for 2020, and a fourth scenario combining rice and wheat export bans:

- REF: Reference case before COVID-19; see IFPRI’s 2020 Global Food Policy Report for further details (link).

- RICE: Rice export bans (100%) in Viet Nam, Cambodia, India, and Thailand along with rice import tariff relief (25 percentage points lower than current levels) to facilitate imports in key rice markets in Asia (Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Philippines) and across Africa south of the Sahara (except South Africa)1.

- WHEAT: Wheat export bans (100%) in key wheat markets based on action by the Board of the Eurasian Economic Commission and individual country governments in the former Soviet Union (Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Ukraine).

- JOINT: Joint implementation of RICE and WHEAT scenarios.

Price impacts

The IMPACT modeling results (Figure 1) show a more than 30% increase in world prices for rice in 2020 under the RICE scenario—perhaps unsurprising given the four countries with simulated restrictions encompass a large portion of the international rice trade. The global wheat market is much more dispersed than the rice market, and the countries of the former Soviet Union represent a relatively small share of that market, so wheat trade restrictions result in a lower, 4% increase in global prices. These results are line with expectations and what others have found (e.g. the blog post from Balié and Valera previously noted) and what appears to be playing out in reality.

The scenarios show only moderate price impacts for non-cereals (increases of less than 4%). However, it is still important to consider such effects in regions where those products account for a large share of the consumption basket or imports. Country-level actions on particular commodities reverberate across the entire agricultural sector and around the globe.

Food security implications

Our modeling also indicates that trade restrictions would lead to regional increases in hunger2 (Figure 2). In the JOINT scenario, a total of 18 million additional people around the world (not including countries implementing trade bans) would face chronic hunger in 2020.

Africa south of the Sahara is the region most strongly affected under both the RICE and WHEAT scenarios, with an increase of 5 million people at risk of hunger under the combined scenario. South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific also see significant effects, with a combined increase of over 8 million hungry in the JOINT scenario. While more insulated from adverse impacts, even Latin America and the Caribbean and the Middle East and North Africa together add 4 million to the population suffering from hunger, demonstrating the far-reaching effects of trade restrictions.

While the countries implementing export bans may effectively avoid increases in hunger in their own populations, the resulting surges elsewhere more than outweigh these effects. Also, the full impacts of COVID-19 in these countries will likely extend far beyond just wheat and rice consumption while additional actions taken by other countries, in turn, can affect those who initiated trade restrictions.

In addition to absolute declines in food access, the relative impacts of calorie reductions also matter. Latin America and the Caribbean and the Middle East and North Africa see greater percentage reductions in calorie availability—but they start off from higher food security levels, and thus see a more modest increase in chronic hunger than Africa south of the Sahara, where millions of people are already close to minimum dietary energy requirements.

Closing thoughts and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has many potential effects that warrant further analysis, especially regarding interacting and compounding challenges both from COVID-19 and from other external shocks such as severe weather events, pest infestations (for example, the current locust problem in East Africa), and civil unrest that may further stress food systems.

Currently, the largest economic shocks from the COVID-19 crisis appear to be on household incomes, while global stocks of rice and wheat are in better shape than they were in the 2007-2008 food crisis. But the fact that relatively few countries export essential staples like wheat and rice poses a potentially significant risk. Our modeling here indicates that trade bans by only a limited number of countries on just two important grains would substantially drive up prices and hunger—suggesting that such actions would have far-reaching impacts around the globe and across other commodities. The case of rice is particularly problematic as it is such a crucial source of dietary energy for so many and has highly concentrated trade markets.

In this context, it is encouraging that ASEAN countries have pledged to avoid pandemic-related trade restrictions. Myanmar and Viet Nam, a major global exporter, lifted rice export limits imposed early in the crisis on May 1, and Cambodia has announced it will restart rice exports May 20. Further action to discourage such export bans may be warranted to help keep food flowing to populations that need it.

Addressing the COVID-19 crisis through trade restrictions causes more problems than it solves; an approach that comprehensively considers the multi-dimensional nature of food systems—from the bowl of rice porridge for breakfast to the need for international movement of resources and products to get them where they are needed—is of utmost importance to get through this crisis as best we can.

Timothy Sulser is an IFPRI Senior Scientist working with the CGIAR Global Futures and Strategic Foresight initiative (GFSF). Shahnila Dunston is a Senior Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Environment and Production Technology Division. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.

1. The RICE and WHEAT scenarios both suggest trade restrictions above the current levels of restrictions in place for exploratory purposes; see food export restrictions tracker (link).

2. The IMPACT model generates several food security indicators. The population at risk of hunger, or the number of hungry, reflects the FAO’s prevalence of undernourishment (PoU, link), and relates per capita availability of dietary energy to minimum requirements.