The COVID-19 pandemic has led to multiple disruptions in food demand and supply, and while in general food systems have proven more resilient than many expected so far, the poor and vulnerable have been hit hardest. In this regard, food prices are a critical indicator. Most food price tracking systems aggregate data that may miss short-term price spikes in specific locations—information that could be used to target relief. Here, researchers from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture describe the development of a crowdsourcing tool for collecting real-time local price data. They used it to capture food prices in locations in northern Nigeria during a 4-week pandemic lockdown period, showing important temporal and spatial price variations for staple foods. Based on their experience, they discuss the benefits and challenges, in emergencies and more generally, of crowdsourcing approaches for food prices.—John McDermott, series co-editor and Director, CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH).

The COVID-19 pandemic and related lockdown measures have disrupted food systems globally, leading to fluctuations in the prices of some food commodities, mostly at the country or local levels. Yet detailed, data-driven evidence of the extent, timing, and localization of food security impacts are rarely available quickly enough or with sufficient granularity to guide policy responses.

Several institutions regularly collect information on commodity prices in low-and middle-income countries (e.g. the FAO GIEWS-FPMA tool, World Food Programme Vulnerability Analysis and Monitoring (WFP-VAM), and the IFPRI Food Security Portal). But they are often unable to generate actionable data on sudden food system disruptions. Price data are often limited in scope because they are monitored at specific markets and often at highly coarse spatio-temporal scales (e.g. monthly and at the [sub-]national level).

Innovating for actionable food price data

The proliferation of mobile phones and internet access in recent years has catalyzed the emergence of innovative data gathering techniques that show great promise in addressing these problems. Citizen participation via digital tools and platforms has the potential to provide near real-time monitoring of food prices while empowering citizens as both providers and users of information. Our recent Food Price Crowdsourcing in Africa (FPCA) project in northern Nigeria, piloted by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) and other collaborating institutions, was initially tested and validated in 2019 and then reactivated during the COVID-19 lockdown in May and June, finding that maize and rice prices dramatically spiked in the midst of the crisis, threatening food security.

Various approaches to crowdsourcing real-time food price data collection have been tested over the past decade in developing countries (Seid and Fonteneau (2017) and Zeug et al. (2017)). Most of these initiatives faced difficulties in achieving meaningful crowd participation, in the large number of crops included, or in setting up efficient data processing methods to derive accurate and representative information.

The FPCA project developed, deployed, and tested a systematized process for crowdsourcing daily prices for a small number of staple foods, presenting the validated data in an open-access web dashboard. Following an initial round of publicity, over 700 volunteers from Kano and Katsina States were invited to submit food price data through a mobile app during visits to any type of market for purchase or mere price checking.

Aware of the challenges faced by earlier crowdsourcing initiatives, we used several approaches for forming a sufficiently large and motivated crowd, and developed a new method for automated quality control and data validation.

To encourage participation, the project employed information leaflets and radio advertisements, nudges (text messages including social norms and information sharing), and micro-rewards (small monetary incentives).

A rigorous statistical routine was developed to automatically check the quality of submitted data and aggregate it over time across locations. In the first step, submitted data were spatio-temporally validated (using the auto-recorded time and geo-location) where closer points (in time and space) are expected to yield similar numbers. In a second step, the data was reweighted to ensure reliability, resembling a formal spatial sampling design (see Solano-Hermosilla et al., 2020 for details). Then the quality-checked data series were disseminated to the public in real time through the web dashboard.

After a testing period (Sept. 2018-Sept. 2019), the resulting crowdsourced data and automated quality control process were validated. The average weekly crowdsourced prices were comparable with those collected from specific markets by FEWSNET, and with monthly data from the National Bureau of Statistics (see Arbia et al. 2020). Similar positive results were achieved with ground-truth checks of data at specific markets in the pilot area.

Based on the successful pilot, the project was reactivated from May 12-June 16, 2020, when lockdown measures were severely disrupting the food system in northern Nigeria. The goal was to assess the platform’s potential to provide timely and accurate information on changing, potentially volatile food prices in a crisis, and to support policy responses to cushion the impacts on food security and livelihoods.

Motivational text messages were sent to volunteers weekly, triggering an immediate resurgence of data submissions. The data showed a steep increase in food prices, trailing the lockdown timeline. Maize and rice prices increased on average by 26% and 44%, respectively, compared to the same period in 2019. Price increases were slightly higher in urban than in rural areas. The data also showed that after lockdown measures were relaxed, prices continued to rise: For instance, local rice continued to be sold at prices 50% higher than in 2019.

Generally, the National Bureau of Statistics reported slightly lower average price increases compared to the crowdsourced data; however, these price reports are published about two weeks after observation, and available as monthly averages by state only. In contrast, the geo-referencing of crowdsourced price submissions can help identify hotspots of high prices.

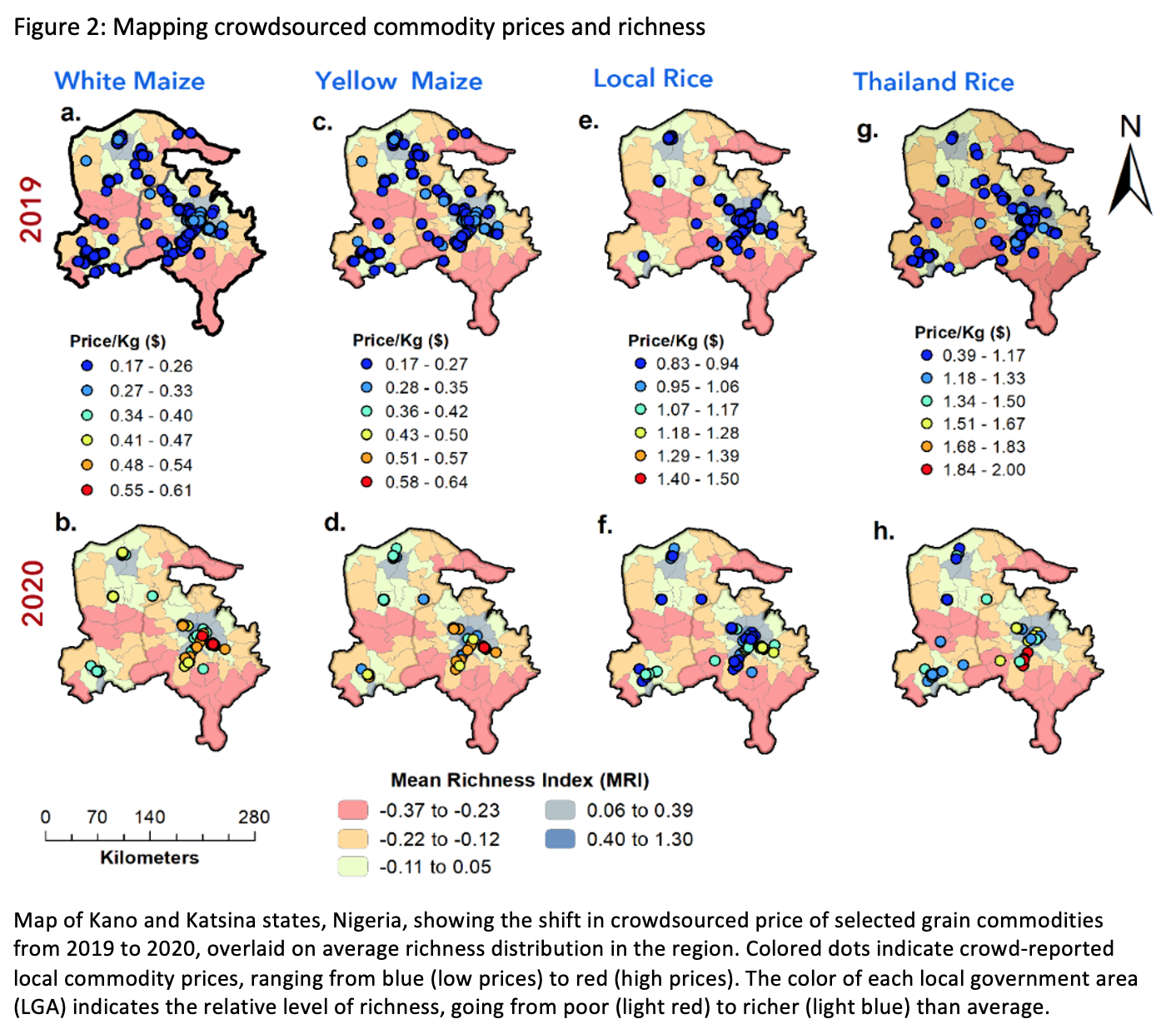

These hotspots were mainly observed in urban areas during COVID-19 lockdowns. Combining the price data with a spatial richness index grid (Figure 2), shows higher prices in May-June 2020 (yellow to red dots) in richer (green-blue shaded), and mostly urbanized areas. But rural areas, where poverty rates exceed 70%, were hard-hit as well, with average price increases of 22% for maize and 42% for rice posing a threat to food security.

The picture in urban areas is complex. Their average level of richness is higher, suggesting that urban households may be better positioned to absorb such steep temporary price increases, for example by reducing non-food expenditures or altering consumption patterns (see recent findings from Ethiopia). But Nigeria’s urban areas are also characterized by high income inequality with a narrow middle-income class and a large number of poor (WB, 2019). Thus, substantial price spikes (rice prices, for example, increased by more than 50% in several urban areas) in combination with job and income losses (NBS-WB, 2020) indicate the COVID-19 crisis threatens food security for low- and middle-income earners in urban areas in addition to the rural poor (Elkahdi et al., 2020).

Lessons and prospects

The successful set-up and implementation of this price tool and platform illustrates the potential of engaging citizens through a mobile app to crowdsource spatially- and temporally-rich data in near real-time. In addition, the ease of activating the tool remotely for price monitoring in an emergency shows its potential in responding to sudden food system shocks.

However, a number of potential concerns remain: Volunteer data contributors may not be fully representative of a region’s population; for instance, educated males living in urban areas were over-represented in the Nigeria project. Additional efforts are needed to boost the participation of more vulnerable populations, and improve the coverage of remote, less populated and often highly food-insecure areas. Also, sustaining data contributions to such platforms over time may be challenging if nudges and/or micro-rewards are no longer available to consistently engage volunteers. The study showed that the crowd could be activated easily and successfully and at relatively low cost in an emergency situation, but the effect of an initial nudge can easily wane with time. Thus, a regular or continuous renewal of the pool of volunteers may also be needed to sustain sufficient data submissions, which is critical for robust aggregation and validation of data, and to maintain the reliability of the crowd.

Overall, our findings suggest that smartphone- and citizen-driven price data collection can complement traditional price data collection systems in terms of timeliness, geographical granularity and responsiveness to market disruptions—not only from the COVID-19 pandemic, but also conflicts, climate shocks, and other problems. This approach can also provide longer-term monitoring of trouble spots to catch incipient price spikes. More generally, policy makers should focus on developing ways to integrate rapid, localized data gathering into their responses. In a world in the grips of rapid systems change, crowdsourcing and other emerging tools will be increasingly necessary for providing timely, well-targeted policy responses.

Julius Adewopo is a Senior Researcher at IITA, Nigeria. Gloria Solano Hermosilla and Fabio Micale are Researchers at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) in Seville. Liesbeth Colen is currently Professor at the University of Göttingen, Germany; she was a researcher at JRC Seville at the time of this project. The views expressed are purely those of the authors, and may not under any circumstances be regarded as expressing an official position of the European Commission.

The FPCA (Food Price Crowdsourcing in Africa) project was funded by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, with partial funding of DG DEVCO under the TS4FNS program. The project was implemented in partnership with Wageningen University and Research (WENR) and the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (IITA, CGIAR).