The social upheavals occurring across Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have equally impacted countries with very diverse politics and public policies—such as Ecuador, Chile, Bolivia, and Venezuela, to name just a few. This convergence should deter those who analyze reality employing general categories such as “progressivism” or “neoliberalism.” It is more useful from the analytical standpoint to take a broader view of the global macroeconomic context—in particular, commodity cycles and how they impact LAC’s unequal and unjust societies.

Although it may seem an exaggeration to go so far back, the history of Latin America and the Caribbean over the last 500 years is marked by two characteristics: Inequality in wealth and income and involvement in global markets, especially with exports of raw materials.

This situation has been the consequence of three different productive structures, each the result of geography and climate. One regional group (especially on the Atlantic coast) based its economy on tropical export agriculture, beginning with sugar production on large plantations with slave labor (later extending to other tropical products). A second group (basically throughout the Andes and north to Mexico) focused on the production of minerals for export (originally gold and silver, then copper, tin, oil, and other products), also exploiting slave labor of native peoples and with agricultural production taking place on large establishments as well. The economy in the third group was based on temperate climate agriculture in the plains of South America (basically Argentina and Uruguay). Lacking minerals or the possibility of producing high-priced tropical products, these regions attracted much less migration than others during the colonial era, and the resulting ranching economy was based on livestock in large production units. These three types of production generated wide disparities in wealth and income (although comparatively much less in the third).

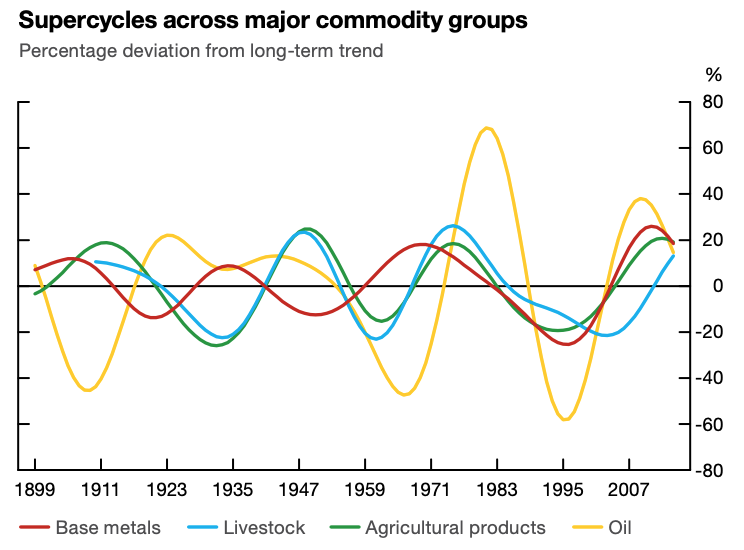

The second main characteristic of the LAC region since its colonial-era integration into world markets is that the evolution of the global economy and commodity cycles have largely determined the performance of its economies.

With these two characteristics in mind (wealth and income inequality and the strong influence of global markets), recent events can be better understood.

The previous raw materials cycle took place from the mid-1970s (when the upswing began) until the second half of the 1980s (when it went into decline). The per capita income of LAC grew around 3.6% per year during the 1970s and then fell to zero in the 1980s, in what the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) called the “lost decade.” Countries with military dictatorships, repudiated for many reasons beyond economic ones, moved toward democracy, while countries with civilian governments also underwent political changes, such as Venezuela, which experienced the collapse of its two traditional parties and the emergence of the movement led by Hugo Chávez.

The most recent commodity cycle started in the first half of the 2000s and peaked around 2011. Since then, commodity prices, with variations, have declined. Between 2000-2011 the per capita income of the region grew at a rate of 2.1% per year; and since then, 0.2% per year. In 2019, of 33 LAC countries with available data, 60% were in recession or stagnation (growing at less than 0.5% annually). These have been the worst 7-8 years in the region since the 1980s, and it is putting the economies, societies, and politics of LAC countries under extreme stress. Some, such as Uruguay and Colombia, have managed to navigate the cycle with effective public policies and democracy, while others, such as Venezuela, have been tragically incompetent and authoritarian. But the declining price phase is affecting everyone, in the context of greater aspirations across the region, the explosion of social media, and a weakening of optimism about the long-term prospects for democracy, an attitude that helped in the post-1980s transition.

The countries of the region owe it to themselves to have a serious discussion, without ideological blindfolds, about how to transform the undoubted abundance of their natural resources into diversified economic growth (to be less affected by global cycles)—and an inclusive and more just society that is environmentally sustainable (if we do not want humanity to disappear), and that maintains democratic values and avoids destructive messianisms.

The debate over “progressivism” vs. “neoliberalism,” in my view, does not clarify much. What matters are specific public policies and their quality of design and implementation—without labels. As Deng Xiaoping said, “it is not important if the cat is white or black, as long as it catches mice.” What our suffering region needs now is a lot of pragmatism and plenty of democratic dialogue.

Eugenio Díaz-Bonilla is Head of IFPRI’s Latin American and Caribbean Program. This post first appeared in La Nación (Argentina).