While we have learned a lot about the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy responses to it, many countries continue to face difficult decisions as they confront new waves of infections and medium term impacts. In this post, Sherwin Gabriel and colleagues present results from modeling the economic effects of short-term social protection measures, especially targeted at lower income households, in the face of new waves of infection and pressure on public expenditures. Results suggest that in addition to the benefits of direct aid, forms of emergency social support have positive macroeconomic impacts.—Johan Swinnen, series co-editor and IFPRI Director General.

Almost 18 months after the onset of economic downturns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries are struggling with uneven recoveries across sectors, as some types of workers and industries are better able to resume their activities than others. Even in the best-case scenarios this recovery would have been precarious, but the spread of new virus variants has cast doubt on the hopes for rapid reopening and recovery, especially for low and middle income countries with low vaccination rates.

South Africa is now experiencing a third wave of COVID-19 infections, accompanied by renewed restrictions on movement and economic activity. Due to the Delta variant’s strong transmissibility, cases have risen dramatically in the province of Gauteng, home to Johannesburg and more than a quarter of the country’s population, and neighboring provinces such as the Western Cape and the North West. In addition to the third wave, recent political violence may have further disrupted recovery. Coping with these challenges and encouraging a strong recovery will require policies that support the populations most vulnerable to them.

In a new discussion paper, we outline the results of a detailed Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) modeling exercise on the near-term economic impacts of extending social support programs in South Africa—finding such action can lead to greater GDP growth, among other outcomes.

South Africa’s economic growth was sluggish and unemployment and poverty were high even before the pandemic. Following extensive restrictions to contain the spread of COVID-19, GDP fell by 17.8% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2020. Economic activity improved in subsequent quarters as lockdowns were eased.

Overall, GDP in the first quarter of 2021 remained a full 3% below that of the first quarter of 2019. While an improvement from 2020, South Africa remains in a deep recession by historical standards. The Delta variant-driven third wave that began in June 2021 prompted the government to reintroduce restrictions at a higher alert level. This situation is likely to produce a limited recovery, or even some backsliding, until a substantial share of the population becomes vaccinated. Currently, only 7.2% of South Africans are fully vaccinated.

As part of its pandemic response, the government implemented aggressive intervention policies to support the incomes of vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, and disabled people. It increased the levels of existing social grants and introduced a temporary Social Relief of Distress (SRD) fund to support unemployed people not covered by other social grants or unemployment insurance. The government was able to do this relatively quickly, as the infrastructure for disbursing grants was already in place. However, top-ups to existing grants ended in October 2020, while the SRD grants were discontinued in April 2021. Thus, vulnerable households entered the new lockdown with a smaller safety net. Almost one fifth of households in South Africa report social grants to be their main source of income. The NIDS-CRAM studies show that household and child hunger remain elevated a year after the pandemic started.

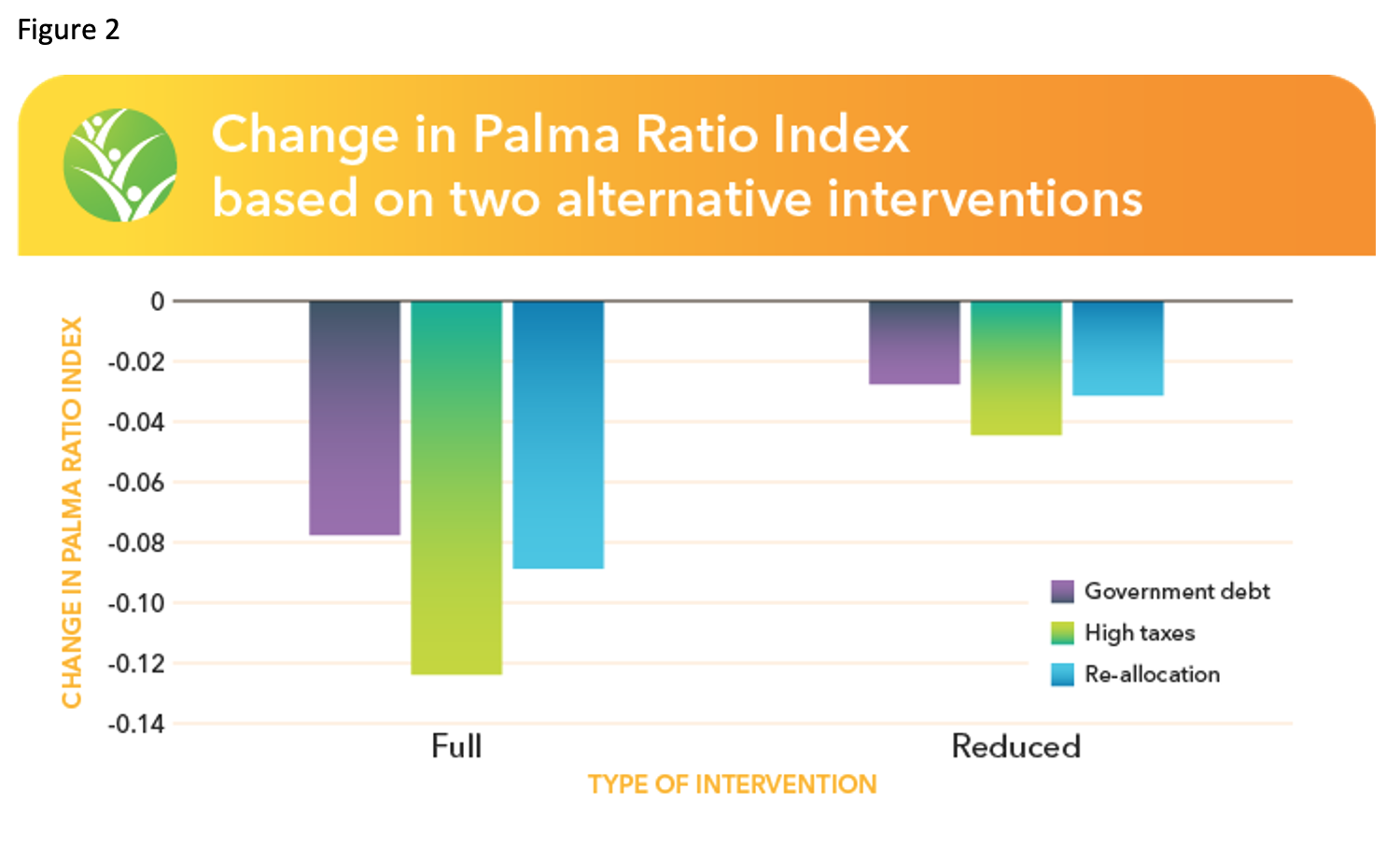

We analyzed the impact of extending income support to vulnerable households through the third quarter of 2021, focusing our analysis on two alternative interventions. In the first, we consider a continuation of SRD support and COVID-19 supplements to social grants for a full year through September 2021 (full intervention). In the second, we consider a continuation of SRD support alone (reduced intervention). We also consider three funding mechanisms: An increase in government debt; increasing taxes on high-income households; or reallocating funds from regular government spending.

Our SAM multiplier model for South Africa uses a starting point that captures the impacts of the economic fall-out during the first six months of the pandemic. The method captures transactions of various commodities by different types of users, such as industry and households, along with other factors. The detail included in the data is comprehensive at both broad industry and household decile levels, allowing some distributional analysis.

As shown in Figure 1, the full intervention, funded by increasing government debt, adds 2% to GDP. Sectors in food and clothing supply chains benefit more, given the propensity for poorer households to spend on these items. When the full intervention is financed by raising taxes of the top 10% of households, a 0.7% increase in GDP is achieved. This comes as higher taxes erode some purchasing power from wealthier households. Still, the net effect on in-year GDP is positive. When funds are redirected to priorities other than current spending, however, the net impact on GDP is a decline of 0.2%. A similar, albeit smaller, pattern is observed when the reduced intervention is considered. Thus, how income support is financed matters.

Because of the policy focus on supporting lower-income households, these interventions are pro-poor. More than half of SRD grant recipients are in the first four deciles, and close to 60% of child support grant disbursements go to households in the first four deciles. Thus, the Palma index, a measure of income distribution, calculated as the ratio of income earned by the top 10% to that of the bottom 40%, is lower in all scenarios, regardless of financing method. In another scenario, in which income support is targeted towards semi-skilled and unskilled workers instead of lower-income households (wage support), the decline in the Palma index is less sharp. This is because most primary- and middle-educated workers fall in the middle of the income distribution.

Notably, except where reducing other government spending is used to offset income support, we estimate that the anticipated increase in government debt is more than offset by improvements in broader economic activity. Thus, government debt to GDP ratios ease slightly, at least over the short term.

The government’s current response to the COVID-19 pandemic is substantially depressing economic activity and imposing enormous hardship on lower income households. These results argue strongly for substantial support targeted at lower income households as a temporary and extraordinary measure during the pandemic period. With strong efforts to vaccinate the population and a bit of luck (e.g., no new variants that evade the vaccine), pandemic restrictions on economic activity should loosen considerably within the next five to nine months. This should be the approximate duration of any additional extraordinary support to households.

Beyond that time frame, South Africa’s policy focus should shift from temporary support for households toward facilitating fairer and more sustainable long-term economic growth with fewer structural impediments. This requires different analytic approaches and different policy solutions, which will be the topic of a subsequent post.

Sherwin Gabriel is a Scientist with IFPRI’s Environment and Production Technology Division (EPTD) based in Pretoria; Dirk van Seventer is a Consultant at United Nations University-World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), Helsinki; Channing Arndt is the Director of EPTD; Rob Davies is a Consultant at UNU-WIDER, Helsinki; Laurence Harris a Consultant with IFPRI; Sherman Robinson is a Research Fellow Emeritus with IFPRI’s Director General’s Office; Jenna Wilf is an IFPRI Project Intern.

This work received financial support from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) commissioned and administered through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für

Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Fund for International Agricultural Research (FIA).