The following blog story by IFPRI gender experts Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Chiara Kovarik, and Agnes Quisumbing was originally published on the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land, and Ecosystems (WLE) Thrive blog. The blog is intended to commemorate the International Day of Rural Women, which is celebrated on October 15, 2015.

Rumor has it that women are naturally the more environmentally conscious sex. As farmers, mothers, and “keepers of the earth,” they are the ones who selflessly care for the planet and are the ones who will bear the disproportionate burden as it is degraded.

But is this really true? While increased attention to women’s issues in agriculture, conservation, and the environment is welcome, especially after having been neglected in development circles for many years, the pendulum seems to be swinging too far. Not all attention is good attention, and overstating the role of women in environmental conservation is not only incorrect, it is also damaging.

To gain a better understanding of the current state of thinking on gender and the environment, we [Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Agnes Quisumbing, and Chiara Kovarik from the International Food Policy Research Institute] recently undertook a review of the literature on gender and sustainability. This review, published in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources, explores the myth that women are inherently more conserving than men.

It traces the root of the theory back to the ecofeminist movement of the 1980s. Ecofeminist scholars posited that women, by virtue of their reproductive roles, are more closely linked to nature and thus are both more likely to conserve it and more likely to be the ones harmed by its ruin. However, we find that the empirical evidence from developing countries presents a much more complex picture.

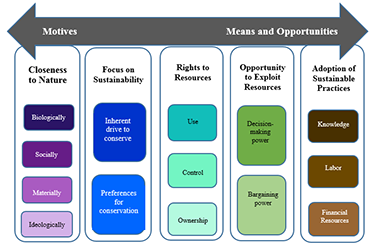

We structure the review around two issues: motives; and means and opportunities. Together they span five categories, moving from the more intangible (which tend to be stressed in ecofeminist literature) on the left to the more tangible (which tend to be stressed in feminist political ecology, intrahousehold, and NRM literature) on the right (See Figure 1 at right). For each category, we present both qualitative and quantitative empirical evidence.

Take, for example, the theory that women are inherently more driven to conserve natural resources than are men. Women’s treatment of the environment is often viewed as motivated by their care and concern for future generations and the earth. However, their actions may be motivated more by the material realities of their situation – such as a desire to keep their own work burdens from increasing or a way to guarantee old age support in communities where women do not control resources – than by a close connection to nature (see Meinzen-Dick et al, page 37, for a discussion and examples).

Other thinking posits that women are not only more driven to conserve than men, but that they also have a greater desire to conserve than do men. While it is certainly true that women’s involvement in natural resource management has benefitted the environment (the Green Belt Movement in Kenya and the Chipko Movement in India are two famous examples), it is not a universal truth that women are interested in the environment. Some studies find that women are uninterested in being involved in forest or land issues (Jewitt 2000; Resurreccion 2006), while others find that women’s involvement may actually result in less sustainable outcomes. Still more research from Tanzania and the Philippines finds that men’s and women’s priorities with regards to water and trees differ greatly, conditioned by their situations and lived realities (German & Taye 2008; Diamond et al. 1997)

The majority of sustainability programs to-date have been gender blind, and have thus ended up working primarily with men, who are more often recognized as farmers, fishers, irrigators, or foresters and who are more likely to occupy public spaces. Certainly women need to be included in discussions and programs concerning resource management, but we can’t assume that will automatically lead to more conservation of resources.

As United States President Barack Obama remarked recently, speaking in Kenya about the need for greater recognition of the roles that men and women play in development: “Imagine if you have a team and you don’t let half of the team play. That’s stupid.” But by the same token, having a team and expecting only half of it to do all the work also won’t work.

If we overemphasize women’s supposed innate desires to conserve resources, or ignore the limitations of the resources (including time, knowledge, financial resources, tenure security, etc.) they need to invest in, agroecology will likely fall short. Instead of either ignoring women or focusing only on them, conserving biodiversity and natural resources, especially as climates change, requires working with both men and women and understanding the gender relations between them.