Can you eat policy?

Obviously not, but without innovations in policy—together with technological innovations in food production, information, and communication that weren’t even dreamed of just a generation ago—there will not be enough nutritious food to feed the world’s growing population.

Last week in Washington, the director generals of the International Rice Research Center (IRRI) and IFPRI, and the chief scientist of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Bureau for Food Security shared their perspectives on how a second green revolution –aimed at not only raising agricultural yields but also improving nutrition and protecting natural resources– is critically needed.

For IRRI Director General Robert Zeigler, the answer lies in science. Rice, for example, is the staple food for half of the world’s population and the majority of its poor, and is critical for global food security. As Zeigler put it, “If you want to do something about poverty, you have to work on rice.” The crop is growing in both popularity—rice is now the fastest growing commodity in Africa south of the Sahara— and in vulnerability, due to climate change-related sea level rise and increasing extreme weather events.

To meet this challenge, IRRI is developing new rice varieties that can thrive even after being submerged in water for up to two weeks and other varieties that are both flood and drought tolerant. “The next green revolution is underway,” Zeigler said.

Climate-smart agriculture—farming techniques that increase productivity, promote resilience in the face of climate change, and reduce agriculture’s carbon footprint—is how USAID is supporting the new green revolution, according to Robert Bertram, chief scientist at the agency’s Bureau for Food Security.

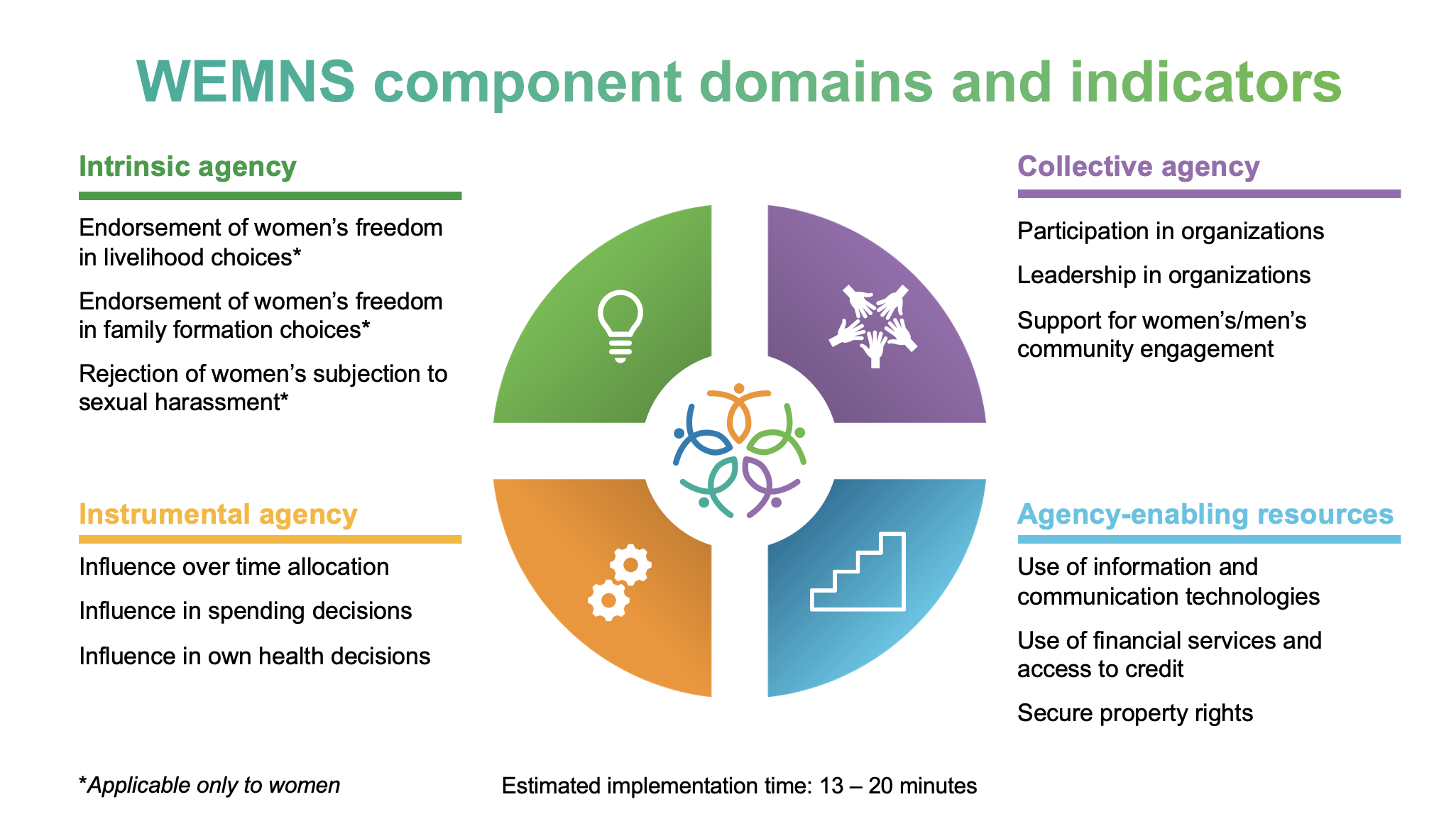

Bertram highlighted several agricultural innovations that work toward this triple win, such as terracing for soil and water conservation, intercropping nitrogen-fixing trees in maize fields, and replanting forests in the Sahel. Scaling up such practices, however, also requires strong policy support. Bertram listed supporting farmer cooperatives, increasing smallholder access to credit, and providing farmers with better access to weather, markets, and price information as key policy components of a climate-smart agriculture portfolio.

Citing recent experiences working within USAID’s Feed the Future initiative, Bertram argued that the goal of current and future food security efforts is no longer simply a matter of getting more food to more people, but making sure the available food is more nutritious. The dual goals of reducing both poverty and stunting is a “huge lift for agriculture,” he admitted. “We need to intensify, via smallholders, with the best technology, and at scale. This is hard, and there is no silver bullet.”

Once the innovative seeds and farming techniques have been developed, the next step is getting them into the hands of farmers, most of whom are smallholders living in remote areas. This is where both data collection and communications technologies—also unheard of a generation ago—enter into the equation. IRRI is using cell phone technology to give rice farmers specific recommendations for fertilizer use, based on crop data collected through satellite radar imagery. “We are at the edge of transforming the way farmers receive and manage information about their crops,” he told the attendees.

However, innovations in policy are critical for success. New policies, and reforms to existing ones, can create an enabling environment for improved farming and seed technologies, and a better allocation of resources, IFPRI Director General Shenggen Fan said. “Policy innovation can be a game changer.” He cited the positive example of Vietnam, which recently opened its rice export market and, on the other side, the export bans in India and the Philippines that contributed to a 200 percent surge in rice prices in 2007 and 2008.

Fan also emphasized the need for new thinking about food systems at the global level, calling for the proposed post-2015 sustainable development goals to be measurable and accountable, and integrated with –nationally driven policies and strategies.

“We have a better understanding in the research community about how important it is to engage in the political agenda,” Zeigler added. “Without that final point all our great work won’t amount to much.”