A pile of numbers, or the key to smallholder resilience in places that need it most?

A data revolution is quietly unfolding in sub-Saharan Africa and empowering sustainable development and resilience for a new generation of policymakers.

Variability in crop and pasture, whether caused by weather, natural disasters, pests and diseases, or political conflict, is arguably the greatest threat to resilience and food security in the Horn of Africa. At the same time, the building blocks of national statistical systems are weak, and data challenges are a crushing reality in Africa.

To address this problem, a growing number of analysts are tackling so-called informational wastelands through open access global and household datasets, pseudo-panels, spatial data analytics and communities of practice.

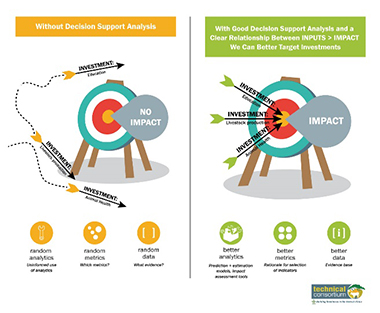

And they’re doing it for good reason. Development practitioners rely on a wealth of data to populate a disaggregated and timely set of ‘appropriate’ indicators to support investment portfolios designed to enhance the resilience of vulnerable populations, particularly those in the Horn of Africa.

Over the last four years, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded CGIAR Technical Consortium for Building Resilience in the Horn of Africa has engaged in research focusing on analytics, metrics and appropriate data to enhance resilience for vulnerable populations in arid and semi-arid regions in the Horn of Africa. Although much of the final work reported in a series of technical papers is proof of concept, collectively it marks the beginning of a growing community of practice in terms of our practical understanding of resilience and theories of change, measuring and monitoring resilience and strengthening the evidence base for resilience capacity. The reports capture nuances in the Horn’s capacity to absorb, adapt, mitigate and recover from shocks and stressors; nuances that may depend on social capital, asset ownership, psychosocial factors and livelihood diversity, to name a few.

For example, analyses led by Tim Frankenberger, president at TANGO International, reveals the importance of relationship networks—within and across tight-knit communities—for mitigating shocks. ‘Social capital appears to have a positive effect on food security, helps households recover, and mitigates the effect of shocks across different datasets’, said Frankenberger. A prolonged shock, however, may eventually erode social capital as upstream resources are used up. Furthermore, poorer households are less poised to receive the benefits of social capital compared to wealthier households, seemingly perpetuating a developmental catch-22 for the poorest of the poor. But, as Frankenberg’s research further illustrates, resilience doesn’t solely depend on social structures or wealth. Sometimes resilience boils down to mind over matter—what the researchers refer to as subjective or psychosocial factors. ‘The perception that people have of their level of control over their own life positively influences their ability to recover from shocks and stressors’, added Frankenberg.

Through a practitioner’s lens, measuring resilience is about measuring changes in well-being status, over appropriate periods of time, in the face of (and following) shocks and stressors. While resilience measurement involves a range of theoretical and technical issues, an early step in the process is selecting the most appropriate indicators.

According to Mark Constas, associate professor at the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management and international professor at College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell University, ‘There exists a need to identify indicators that will enable one to assess the well-being of individuals and groups who live in shock prone contexts and determine why some individuals and groups recover better than others’. Conducting primary data collection studies is one response. However, as Constas explains, ‘From an efficiency perspective, it also makes sense to leverage existing data to the fullest extent before launching new, and often costly, data collection efforts’. Based on a matrix that specifies the types of indicators and properties of indicators required to study resilience, Constas et al. (2015) developed a review framework that supports efforts to exploit existing datasets for resilience analysis. Initially conceptualized as proof of concept, the framework represents the first steps in much needed data-mining activities geared towards resilience analysis based on standardized data architecture.

Perhaps the Technical Consortium’s most tangible and immediately implemental outcome is the creation of a knowledge-sharing platform. Led by research fellow Jawoo Koo from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the platform allows policymakers access to a multi-faceted set of resilience indicators for evidence-based planning and investment in the Horn of Africa. It is built on the CKAN open-source data portal software, providing online data visualization, analytical functions, and application programming interfaces (APIs) for exchanging data with other applications or platforms. Indicators are harmonized over time and space; a unique characteristic of secondary datasets. Although regionally tailored for the Horn, the platform is theoretically transferrable without regard to program, scale or location.

“It’s a methodology and a start, that’s what’s exciting,” said Katharine Downie, senior scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and coordinator of the Technical Consortium. “We can start replicating this framework and practitioners will be able to plug this [resilience] template into their own programs.”

Data, however, come with a hefty price tag. “I wish we could do this in every country, but it takes money and, unfortunately, work on data for data’s sake isn’t particularly sexy, primarily because it doesn’t produce a tangible outcome to validate the investment,” Downie said. “Data may reflect impact but data alone will not produce impact. Given this, the work of the Technical Consortium has focused on developing tools and analytics, but also ensuring that data is accessible and can be strategically applied. This is what makes the data on resilience more valuable.” And, as we are all aware, overly ambitious household surveys and primary data collection are also expensive. And maybe we’re casting too wide a net. “Smaller, more serial and targeted measurements are probably the way forward in data gathering,” added Nancy Mock, professor at the Payson Graduate Program in Global Development at Tulane University Law School.

At the end of the day, resilience doesn’t come from numbers. It’s about aligning research with development, smart investments, quality, well-organized data and evaluating innovation, and that all requires good information. That is, if donors and governments are willing to spend money on good data—albeit inherently unglamorous—for the good of the people.