Conflict, economic shocks, and climate change and natural disasters continue to put too many lives and livelihoods at risk of hunger around the world, according to the Global Report on Food Crises 2019. With only a slight fall in the number of people facing acute levels of hunger globally—from 124 million in 2017 to 113 million in 2018—the number technically in crisis has surpassed 100 million for the past three years.

The annual report—including the latest estimates on severe hunger and analysis of the situations of countries chronically vulnerable to food crises—is published by the Food Security Information Network (FSIN), a global initiative of IFPRI, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Food Programme (WFP). An April 26 policy seminar at IFPRI headquarters explored the latest report’s key findings.

“The level of humanitarian requirement in the world has been increasing dramatically in the last 10-15 years, and is now at $27 billion per year, 40% of this is for food security-related issues,” said FAO Senior Resilience Advisor Luca Russo, who sits on the FSIN Steering Committee.

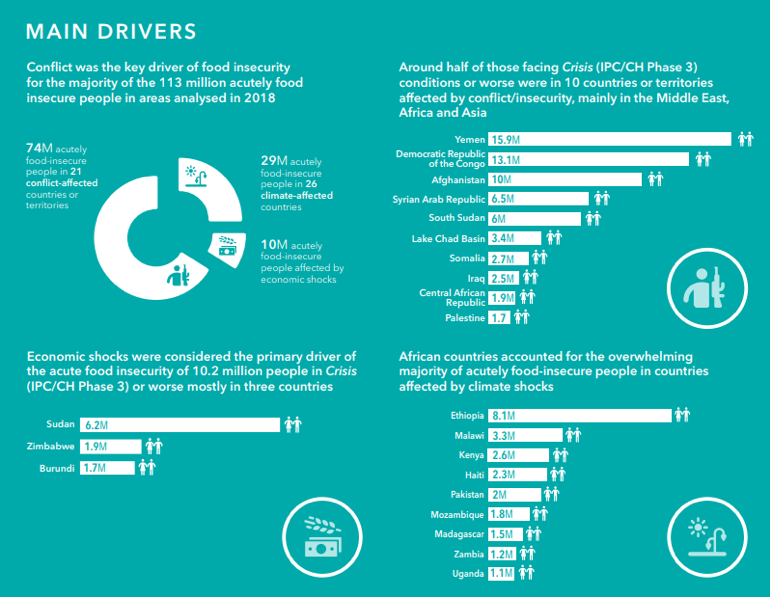

He noted that of the 113 million people in 53 countries experiencing acute food insecurity (IPC/CH Phase 3 and beyond), 72 million people— two thirds—are concentrated in eight countries, including, in order of severity: Yemen, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Syria, Sudan, South Sudan, and northern Nigeria. Ethiopia is the only one of those not affected by conflict. “What we see is just the tip of the iceberg; we have 143 million people in IPC/CH Phase 2 in 42 countries at the verge of destitution now. Unless we take preventative action on this category of people the number will continue to increase,” Russo said.

Global Report on Food Crises 2019

Conflict—including social unrest, political crisis, and localized violence—was the primary driver of food insecurity affecting 74 million people in 21 countries, said FSIN Secretariat Coordinator and WFP Senior Programme and Policy Officer Anne-Claire Mouilliez. Climate and natural disasters pushed another 29 million to face acute food insecurity, with an overwhelming majority of them in African countries. Economic shock was the third main cause for acute food insecurity, affecting 10.2 million people mainly in Sudan, Zimbabwe, and Burundi. On nutrition, the report shows women and children suffer higher levels of chronic and acute malnutrition due to poor access to nutritious food and limited health and sanitation services.

Forecasts for 2019 will most likely show similar figures, with no signs of decreasing conflict, climate shocks, or economic instability, as well as ongoing threats of disease outbreaks such as cholera, measles, and Ebola. “The report demonstrates the critical importance of reinforcing safety nets and investing in conflict resolution and peace, knowing that it has been the primary driver for two-thirds of the caseload,” said Mouilliez.

Global Report on Food Crises 2019

Following the overview, presenters focused on country experiences that demonstrate the impact of conflict on food security.

“Food is a weapon of war, a tool of political control and a source of corruption. We need to change the cost-benefit analysis of those using it” in those ways, said Eugenio Diaz-Bonilla, head of IFPRI’s Latin American and Caribbean Program. In Venezuela, he explained, bad macroeconomic policies, corruption, political control, and the decline of democratic institutions led to a severe food crisis. Figures from 2017, the most recent available, show that over 80% of Venezuela’s population suffers from moderate to severe food insecurity. To address the crisis in the short term, Diaz-Bonilla said, food aid and medicine must go through a variety of reliable existing channels including civil society, churches, and non-politicized social networks.

Bangladesh has taken in 800,000-1 million Rohingya refugees fleeing violence in Myanmar. Though its food system has so far been able to accommodate them, medium- and long- term solutions will be needed, said Paul Dorosh, director of IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division. There are few employment opportunities for the Rohingya, Dorosh said. An IFPRI joint study with the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, he noted, shows that independent access to food is quite limited, and while voucher and direct food distribution programs helped avert crisis and maintain displaced people’s nutritional status, if inadequate, these won’t be sufficient going forward. Programs must also grapple with donor fatigue and challenges of education, employment, and freedom of movement for the Rohingya.

“If we think about humanitarian aid that supports dietary quality, the most promising approach is cash transfers,” said IFPRI Associate Research Fellow Sikandra Kurdi. Kurdi cited Yemen’s 34 recent percentage point increase in acute child malnutrition for children under 5—from 16% to 50%—explaining that the country’s ongoing war presents significant challenges for humanitarian aid in avoiding long term negative developmental consequences of childhood malnutrition. A recent evaluation, Kurdi said, demonstrates that cash transfers combined with nutritional education sessions led to improved feeding practices and better access to high quality food that improved childhood nutrition outcomes in Yemen. This finding provides strong support for cash transfers’ effectiveness in crisis situations in general.

“We need to promote greater coherence and better effectiveness of collective efforts across the humanitarian-development-peace nexus,” said FAO Director of Emergencies Dominique Bourgeon, noting the discussion at the Global Network against Food Crises (GNFC) launch event for the report in Brussels on April 2. “We need to put more attention on the early warnings to predict and anticipate necessary actions, collaborate across sectors to address the various drivers, while generating political uptake at all levels and strategic investments,” he said.

Without good food policies, food problems won’t be solved, said World Bank Practice Manager Dina Umali-Deininger, outlining two areas where the organization is helping with food crises: Emergency response and development assistance. The bank releases funds quickly in countries where major disasters and severe economic crises occur, and support countries that absorb refugees and displaced peoples. The World Bank also promotes climate- and nutrition-smart agriculture programs and aims to create an enabling environment for good food policies.

“Food security is a dynamic concept, but our measurement is static,” said WFP Chief Economist Arif Husain. Rolling assessments on a weekly and daily basis can help create a better understanding of the sensitivity of food security information to forces on the ground. Technological systems currently under development by the private sector also have a lot to offer the humanitarian sector. Husain added: “Our job now has changed from just collecting data, to making data talk.”

Ahdi Zuber Mohammed is an FAO Communications and Partnerships Consultant; Katarlah Taylor is an IFPRI Senior Events Specialist.