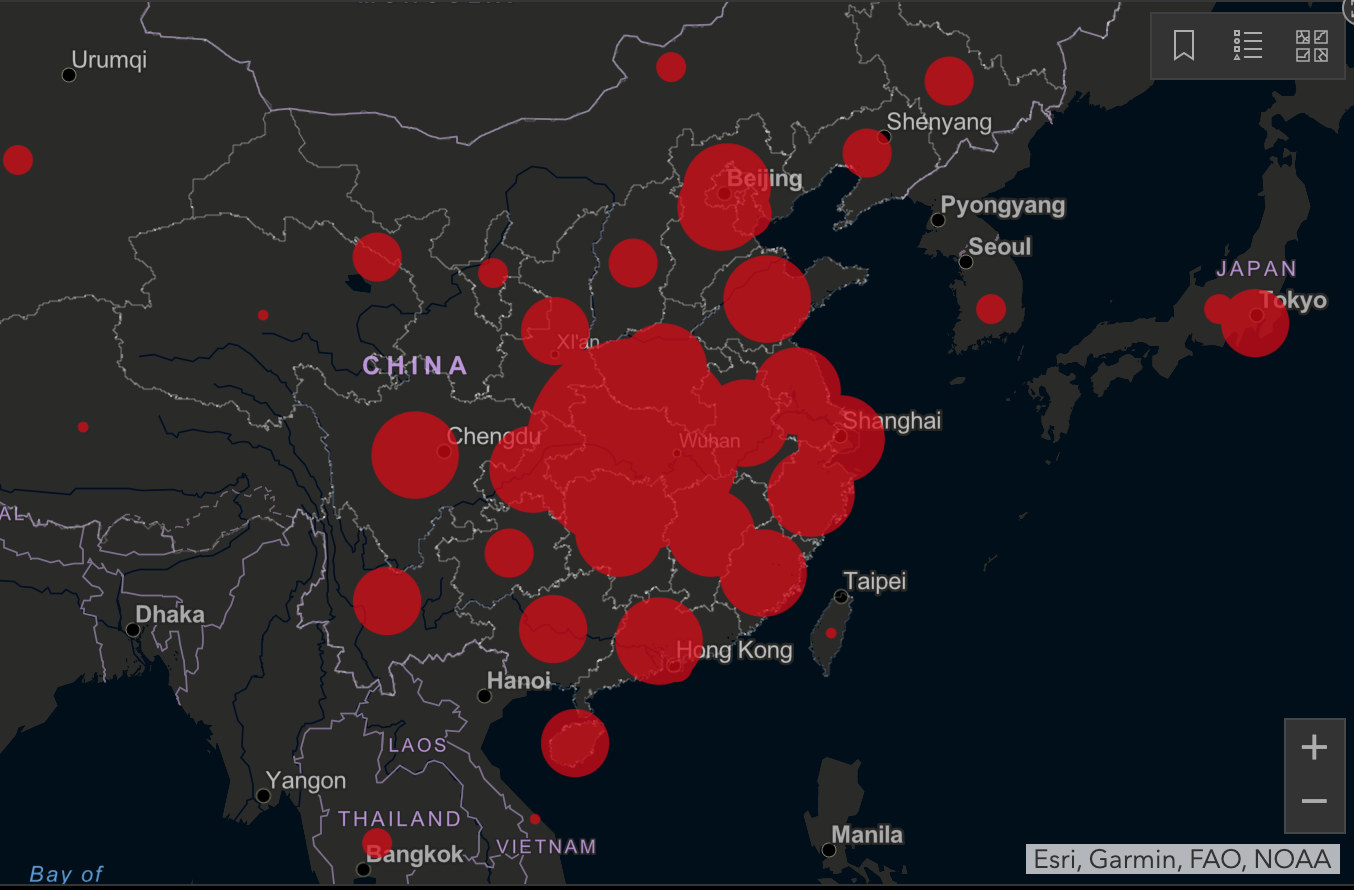

The current novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak originated from a seafood and wild food wet market in Wuhan and has quickly spread across China and to at least 25 other countries, causing more than 1,000 deaths (virtually all in China). China has imposed controls on movement both within its borders and at international boundaries to contain the disease. While these measures are necessary, they could potentially lead to hiccups in food and nutrition security. Pandemics like Ebola, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) all had negative impacts on food and nutrition security—particularly for vulnerable populations including children, women, the elderly, and the poor. For example, when Ebola began to hit Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone in 2014, rice prices in those countries increased by more than 30%; the price of cassava, a major staple in Liberia, skyrocketed by 150%. In 2003, the SARS outbreak delayed China’s winter wheat harvest by two weeks, triggering food market panics in Guangdong and Zhejiang, though production and prices were largely unaffected in the rest of China.

Since the beginning of the outbreak in December, food prices have remained stable in Wuhan, in Hubei province—and in fact, all over China. Supplies of staples, fruits, vegetables, and meats have been adequate despite sporadic reports of price hikes and shortages in isolated locations. But there is no room for complacency. Media reports indicate that the poultry industry is already under stress due to a lack of adequate feed supply and interruptions in the timely marketing of its products. If nothing is done, the poultry supply could begin tightening, and these problems could spread to other industries—creating a food supply hiccup and a threat to food and nutrition security for many.

The current situation

Disruptions are not expected to be severe in the short term, as food supply has been sufficient and the market has been basically stable, at least so far. Wuhan has been under lockdown since Jan. 23 to contain the spread of the virus. Restrictions on transportation and movement of people have led to some food logistics challenges. However, as the lockdown began just before the Chinese New Year Jan. 25, most citizens had already stocked food, and businesses had established reserves of goods for the holidays, so food prices have not been significantly affected.

The poultry industry has already been affected and its troubles will worsen over time without action. Transportation blockages bring difficulties for distribution of inputs like feed, and some firms have already encountered input shortages, difficulties in product delivery, and labor shortages. The ban on the movement of live poultry (believed to be a potential disease risk) has stopped farmers from getting chickens and eggs to market, which has leds to some burying chicks and ducklings alive. According to industry estimates, market input of chicken and ducklings has decreased by about 50%. Supplies of meat could plunge, coupled with the extended impact of African swine fever.

The food system beyond agriculture has also been significantly affected, and these impacts will grow if processing enterprises cannot restart production in a near future. Only 24% of agricultural products are directly consumed by households, while 77% are used as intermediate inputs, 41% go to food processing enterprises, and 3% are used by restaurants. In the wake of the coronavirus outbreak, many orders were canceled and many restaurants had to close their doors. The supply of processed foods remains relatively abundant for the time-being, but production may also be affected by a lack of workers and falling demand for agricultural products. One priority, then, is allowing migrant workers to return to these jobs.

Production of staple food crops such as wheat, rice, and vegetables will be affected if the outbreak continues into the critical spring planting period. Whether agricultural inputs can be distributed in time for spring planting remains unclear. The 2014 Ebola epidemic led to an increase in abandoned agricultural areas and reduced fertilizer use in West Africa. If staple food production is affected, the impact on food security could be grave.

Domestic and international trade disruptions may trigger food market panics. During the 2003 SARS outbreak, panic-buying of food and other essentials hit many places in China. If this happens again, it would exacerbate temporary food shortages, lead to price spikes, and disrupt markets. If not controlled quickly, food panics can spread and threaten broader social stability.

Restrictions on mobility may lead to labor shortages. Many companies have given workers extended leave in response to the outbreak; this could leave many manufacturing and service enterprises without enough workers. Large numbers of migrant workers who returned to their hometowns for the New Year break are now trapped there because of quarantine measures. The resulting labor shortage will likely impact both domestic and global supply chains.

Fortunately, the government is targeting these problems. Premier Li Keqiang has called on ministries to coordinate to ensure an ample supply of food and effective logistics for delivering agricultural inputs, emphasizing the responsibility of local governors. Feed production and slaughter enterprises are required to accelerate production in order to restore and increase the effective supply of livestock and poultry products. They are also being provided with production guidance and technical services to strengthen animal and plant epidemic prevention and control. But all of these measures must be implemented effectively, and as soon as possible, to avoid a hiccup in supply.

Looking forward

It’s unclear how long the outbreak will last. According to the World Health Organization, it is too early to declare it has peaked. If SARS is any indication, the outbreak could drag on for months or longer, possibly into May at least. Based on the lessons and experiences of previous pandemics and the current situation in China, we offer the following suggestions on how China can prevent a hiccup in food and nutrition security:

Continue to closely monitor food prices and strengthen market supervision, particularly in Wuhan and across Hubei and nearby provinces. Transparent market information will enhance the government’s overall management of the food market, help to prevent the onset of panics, and can guide farmers in making rational production decisions. The potential for speculation remains at every stage of the supply chain, so there is also a need for sound market supervision to keep order. Quality supervision of processed products is also important to maintain food quality and safety.

Ensure smooth logistical operations of regional agricultural and food supply chains. The government has already made several moves in this area. It has opened a “green channel” for fresh agricultural products and prohibited setting up unauthorized roadblocks. On Feb. 4, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs issued an emergency notice calling on related departments to maintain order in markets and ensure ample supplies of meat, eggs, and milk. But to work, these policies will require close supervision. In addition, e-commerce and delivery companies can also play key logistical roles. For example, as lockdown measures have led to a huge spike in demand for home delivery of fresh groceries, e-commerce companies have announced an in-app feature for contactless delivery, allowing the courier to leave an order in a convenient spot for the customer to pick up, without having to interact. Making use of these delivery platforms could address many logistical challenges for obtaining food, while minimizing the potential risk of infection from visiting crowded markets to buy groceries.

Introduce enabling policies for spring planting and increase support for production entities. Agricultural enterprises need financial support to avoid depleting their credit and to help reduce financing costs; agriculture in general will need support to make sure that the spring planting season proceeds normally. The government could mitigate the burden on farming enterprises by reducing or delaying their tax and social insurance premium bills and lowering their rents. It should also consider providing temporary subsidies for farmers.

Ensure the smooth flow of trade and make full use of the international market as a vital tool to secure food supply and demand. After reaching the phase-one trade deal with the United States to buy $40 billion-$50 billion of U.S. farm products annually for the next two years, China has further announced it is cutting tariffs on U.S. goods to ensure supplies and to alleviate economic and trade frictions. Meanwhile, increasing livestock product imports could help to buttress supply and stabilize the prices of domestic livestock products.

Protect vulnerable groups and provide employment services to migrant workers. International experience shows that the impacts of pandemics fall disproportionately on vulnerable populations, including children, pregnant women, elderly people, malnourished people, and people who are ill or immunocompromised. If many workers unable to earn an income due to the disruptions of the outbreak, that risks an increase in poverty. As the government manages the epidemic response, it will be essential to restore the income streams of migrant workers and normal business operations. Workers should be encouraged to find jobs near their homes and migration managed to prioritize their health. There is also a need for accurate and timely information to match workers with companies.

Regulate wild food markets to curb the source of the disease. Many zoonotic diseases originate from wildlife; HIV, Ebola, MERS, and SARS have all made the leap from wildlife to humans, spawning international outbreaks. On Jan. 26, the government announced a temporary ban on wildlife trade from markets, restaurants, and e-commerce until the epidemic is over. This move may temporarily reduce human contact with wild animals. But it is important to step up research and craft long-term legislation to close the major legal loophole allowing trade in wild animals in order to avoid future epidemics.

Kevin Chen is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s East and Central Asia Office in Beijing and Chair Professor at Zhejiang University. Yumei Zhang is an IFPRI Visiting Research Fellow and Senior Research Fellow with the Institute of Agricultural Economics and Development of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Yue Zhan is a Research Assistant with the IFPRI East and Central Asia Office. Shenggen Fan is a Chair Professor at China Agricultural University and former Director General of IFPRI. Wei Si is a Professor at the College of Economics and Management, China Agricultural University. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.