Lockdowns imposed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have disrupted food markets across India. Sudha Narayanan of the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research explains that nevertheless, parts of the food system have thus far proven “surprisingly resilient”—and that what happened can only be understood taking into account the complexity and variety of India’s food supply chains. The government, traditional retailers, and innovations in supply chains all played key roles in response to the crisis. However, many challenges remain, with food insecurity still high and much uncertainty ahead.—Johan Swinnen, series co-editor and IFPRI Director General.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indian government imposed a stringent national lockdown from March 24-May 31 that caused severe disruptions across agrifood supply chains from “farm to fork” (Ramakumar, 2020; Rawal et al., 2020). The government was consistently one step behind in terms of preventing these problems (Narayanan and Saha, forthcoming1).

The lack of labor and machinery disrupted harvests and brought warehouse operations to a virtual standstill. Regulated markets where farmers sell produce were intermittently closed and village traders and merchants did not show up to make purchases. Our survey of around 370 farmers across nine Indian states found that among those who had harvested some produce this season, 29% were still holding on to it; 13% had sold the harvests at throwaway prices and about 7% reported that they had to let the produce go waste.

Lockdown-related problems also made it extremely difficult for many retailers to secure fresh and processed foods and to conduct business (Narayanan and Saha, 2020).

Food markets in India, both in urban and rural areas, constitute a mosaic of diverse actors and tend to be highly fragmented. How did this complex system cope in the wake of lockdown? Despite the early confusion, anxiety, and disruptions, there is now widespread consensus in India that the agrifood system has been surprisingly resilient. Nevertheless, the lockdown’s impacts continue, and their dynamics deserve attention from policy makers and organizations working on ways to protect food security. This post outlines five key features of the lockdown’s consequences for the Indian agrifood system, noting that these are broad patterns that mask large variations.

Consumer prices rose on average while producer prices crashed

Two broad impacts on prices are evident from existing data. It appears that the overall decline in demand, especially in cities—driven in part by the fall in hotel, restaurant, and catering demand and in part by the large exodus of migrants—has flowed upstream, leading to a substantial fall in producer prices. One producer price index suggests that after a brief rise, prices crashed to almost a third of the pre-lockdown prices by the end of May (Figure 1).This is consistent with findings from farmer telephone surveys as well, where many report a dramatic collapse in prices, especially for perishables.

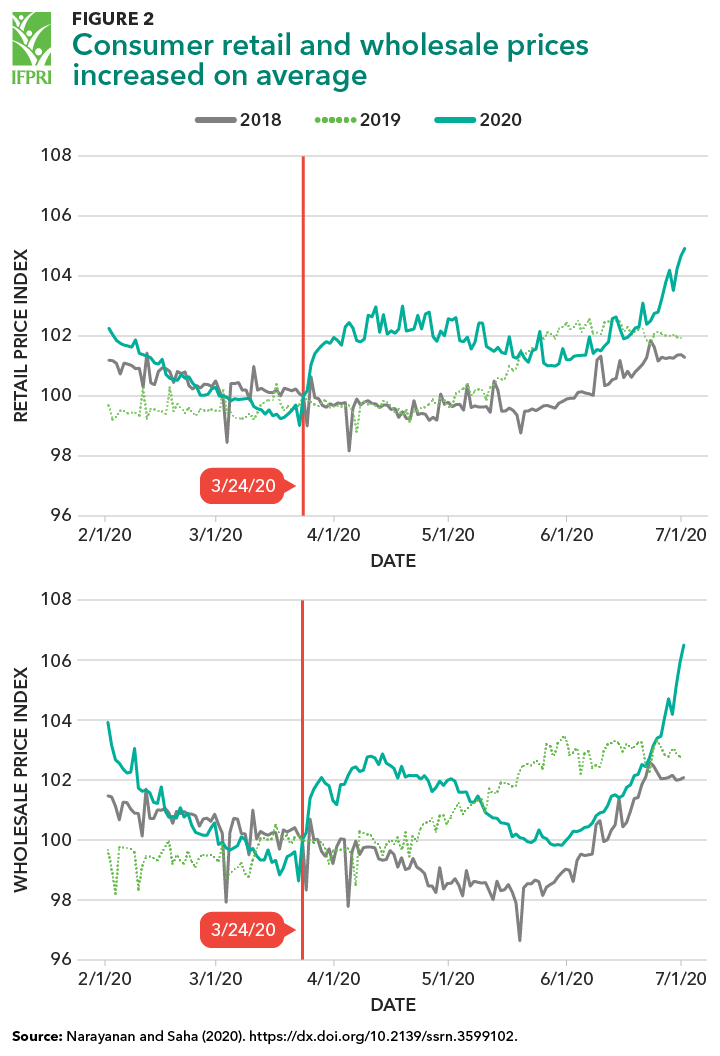

At the same time, consumer food prices in most urban areas have risen, driven by increased frictions in the supply chain in the form of limited availability of labor, higher transport costs (in some cases, double pre-lockdown costs) and uncertainties around logistics (Figure 2). This gap between wholesale and retail prices increased sharply during the first phase of the lockdown (March 24-April 14) and remains wide (Narayanan and Saha, 2020).

Heterogeneity of impacts and some improvements over time

These disruptions fragmented markets across rural and urban areas. In some large cities, average retail prices did fall, with increases for just a few commodities; but in smaller cities and towns for which data are available, retail prices rose an average of more than 20% in the two months following the lockdown. In addition, the range of prices across urban centers increased significantly during the lockdown, signifying a lack of spatial integration; wide variations persist even after two months, suggesting continuing challenges.

The price trends of different commodities have varied as well. Producer prices for perishables collapsed, and retail prices for fruits and vegetables have fluctuated widely over time and space—increasing substantially in some areas, declining in others; and rising since the lockdown in some cities. In contrast, producer prices have stayed high for major cereals, likely because of active government procurement, and retail prices in urban markets did not rise—due to the Public Distribution System (PDS) that supplies grains to consumers, and also likely because of large scale grain distributions to vulnerable populations by civil society organizations. Retail prices for pulses and edible oils, and for processed goods such as biscuits and flour, however, rose sharply.

The role of traditional retailers has been instrumental

Up to 90% of the Indian market is served by small-scale mom-and-pop/corner stores (called kirana) and other informal players such as push-cart and street vendors; about 8% by supermarkets and other modern outlets; and 2% by online merchants.

It is kirana stores and informal street retailers that have most successfully managed to negotiate the challenges of the lockdown. Informal retailers, commentators note, have “embraced technology,” receiving assistance at the back end from B2B (business to business) retailing supply chain management firms.

While these retailers also rely on hired workers, most depend heavily on family labor and were therefore less affected by labor shortages than modern retailers. Street vendors of fresh produce have also kept supply chains functioning. Findings from a survey of over 50 retailers in 14 locations across India suggest that some people who lost jobs in cities and could not return to their home villages, or had shops closed due to lockdown restrictions, switched to vending fresh produce and groceries. In Porvorim, Goa, for example, one fruit vendor said that around 30 people in his neighborhood, including a car mechanic, opened up fruit and vegetable shops because they were out of work and could not return home. The low entry barriers to informal retail led to an expansion in the number of informal retailers of food during the lockdown.

Some thought modern organized retailers, with their strong back-end investments, would be the best placed to operate during the crisis—however, limited labor availability and movement restrictions severely hampered their operations. While online prepared/restaurant food delivery orders (referred to as “foodtech”) dropped by 75% in April compared to January (and overall e-commerce fell by 83% over this period), e-grocery demand in contrast rose by 27%. Yet despite sophisticated procurement and stocking systems, only a fraction of online orders were fulfilled due to distribution challenges, including labor availability. Most online food retailers halted operations; several continue to struggle to meet the surge in consumer demand. Modern format retail stores, meanwhile, many located in shopping malls, have remained shut for most of the lockdown.

The roles of government procurement and private innovation

Producer prices have held up for crops that have seen large scale government procurement. For example, as of June 20 the government had procured 38.83 million tons of wheat from ten wheat-producing states. Many state governments had also arranged to facilitate local procurement of milk and horticultural products for direct distribution.

The lockdown has also prompted a number of important private sector innovations. For example, during this period many farmers began delivering produce directly using WhatsApp to secure aggregated orders in housing cooperatives in nearby cities. As many farmers’ markets shut down, meanwhile, some farmers traveled to cities to set up shop at roadsides. Consumer-led groups on Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp organized with Farmer Producer Organizations to find ways of bringing food to markets (Narayanan and Saha, 2020). In general, as Reardon et al. (2020) anticipated, large-scale processing firms were able to continue functioning, most at lower capacity. Even these larger firms had to cope with distributional challenges by leveraging online delivery platforms that were previously servicing restaurants. Many restaurants in large cities too pivoted to selling groceries and produce via online delivery platforms.

Food insecurity remains high

Under the national lockdown, people in urban areas were likely more vulnerable to food insecurity than those in rural areas, especially those dependent on wage employment. In one survey of 11,159 workers conducted during the lockdown, an estimated 96% said they were not receiving rations from the government due to eligibility or implementation problems, 72% said that their rations would run out in two days, and 90% were not receiving wages (SWAN 2020). In rural areas, meanwhile, the collapse in producer prices and farmers’ difficulty selling their produce imply lower prices and greater availability of a variety of foods. Yet, in many regions, food security remains high, mainly because of a large loss in incomes, according to several telephone surveys of rural workers and farmers (Singh, et al., 2020; Seth and Vishwanathan, 2020).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 lockdown offers a teachable moment for Indian policy makers: That while their country’s people are largely vulnerable, the food system is resilient. When and where need exists, in other words, intervening at key points in food systems and providing direct assistance can prevent widespread economic and food insecurity. While the Indian government has turned its attention to agricultural policy reform, the immediate focus should be on relief. The government has already implemented modest cash transfers to farmers and other vulnerable populations, revised loan repayment schedules, expanded the entitlements of grain under the PDS and additional allocations for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). Yet recent reports suggest that despite these actions, many people continue to be excluded from benefits due to eligibility restrictions or implementation issues. Universalizing the PDS and employment guarantee, along with other food-based schemes such as maternity and child entitlements, and providing more effective implementation, should be top priorities.

In rural areas, especially those underserved by markets, providing decentralized public procurement and distribution of fresh produce, in addition to cereals, pulses and oilseeds, is crucial to moderate producer prices and ensure availability and affordability of foods locally. In cities, urban governments need to facilitate the free functioning of supply chain actors. Many states have introduced urban employment guarantee schemes to protect people from job and income losses. Other state governments have organized door delivery of groceries, along with canteens that provide cooked meals at affordable rates. Such measures are especially crucial until supply chains are fully restored.

Sudha Narayanan is an Associate Professor with the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research in Mumbai.

1. Narayanan, Sudha and Saha, Shree (forthcoming) One Step Behind: The Government of India and Agricultural Policy During the Covid-19 Lockdown, Review of Agrarian Studies.