Since the COVID-19 pandemic, global income inequality has again started to rise—a trend exacerbated by the food and fertilizer crisis caused by Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine (The Economist 2022). Increasingly common disasters (many climate-related) across the globe – such as Pakistan’s devastating 2022 floods, ongoing severe drought in the Horn of Africa, and the recent earthquake in Syria and Türkiye—also disproportionately affect already vulnerable groups. Such events tend to further exacerbate the gulf between the rich and the poor. This trend toward greater income inequality is notable, given a growing body of research has demonstrated that citizens’ support for and trust in government is heavily influenced by real as well as perceived income inequality (Gimpelson and Treisman 2018, Healy et al. 2017).

Trust in government is essential for a functioning democracy. It is also critical for the economy—for example, Fukuyama (1996) highlights how social trust plays a role equal to that of physical capital in determining economic prosperity. Governments often address poverty and inequality through redistributive social protection programs, including cash transfer programs. Can such programs foster trust in government amid increasing inequality? Evans et al. (2019) show that they can increase trust in leaders and perceptions of leaders’ responsiveness and honesty among recipients. But the empirical evidence is mixed, and other studies show that this does not occur consistently (Freeland 2007, Ellis and Faricy 2011, Zucco 2013).

Understanding of how economic welfare affects political attitudes and behavior continues to evolve. Classical economic voting theory focuses on absolute welfare, holding that citizens reward the government for good economic outcomes and punish it for bad ones. However, an emerging literature in political science suggests that perceived relative well-being—how people see themselves compared with others—is also important in shaping citizens’ assessments of their political leaders and institutions.

In Kosec and Mo (2023), we studied how Pakistan’s national unconditional cash transfer program, the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), affected political attitudes. Specifically, we considered that cash from the government might have different effects on its recipients according to how economically well off they felt relative to others (and thus presumably how in need and deserving of a cash transfer they felt).

Empirical approach

In 2010, the Pakistani government used a proxy means test to identify BISP beneficiaries. In other words, the probability of being a BISP beneficiary jumped at a threshold family wealth score, enabling us to employ a regression discontinuity design approach to assess the causal impact of the BISP program (see Figure 1). To assess the effects of cash transfers on political attitudes—specifically, support for leaders and the broader system of governance in Pakistan—we compared the political attitudes of those who just met the threshold for receiving cash transfers to those who just missed it. As the cut-off score was somewhat arbitrary, the two groups were naturally very similar to one another.

Figure 1

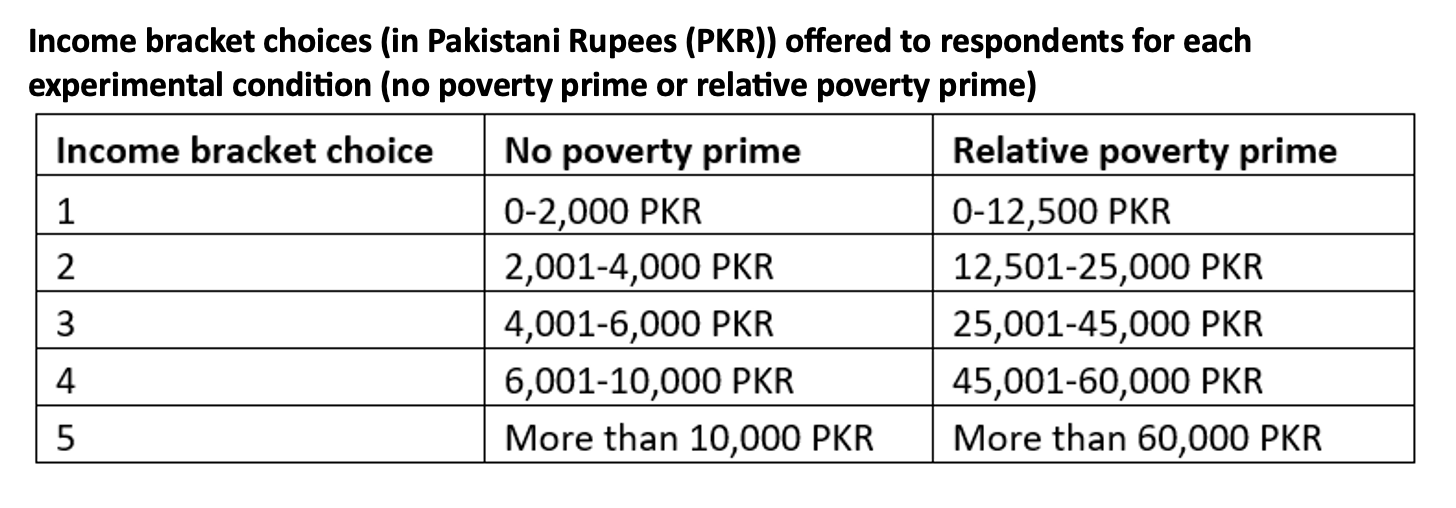

To evaluate whether perceptions of one’s relative economic position conditioned effects of cash transfers, we conducted a priming experiment which subtly manipulated respondents’ perceptions of their relative economic position. Specifically, we asked respondents which of five given income brackets described their household’s monthly income, and manipulated the range of the bracket choices offered to them (see Table 1).

Table 1

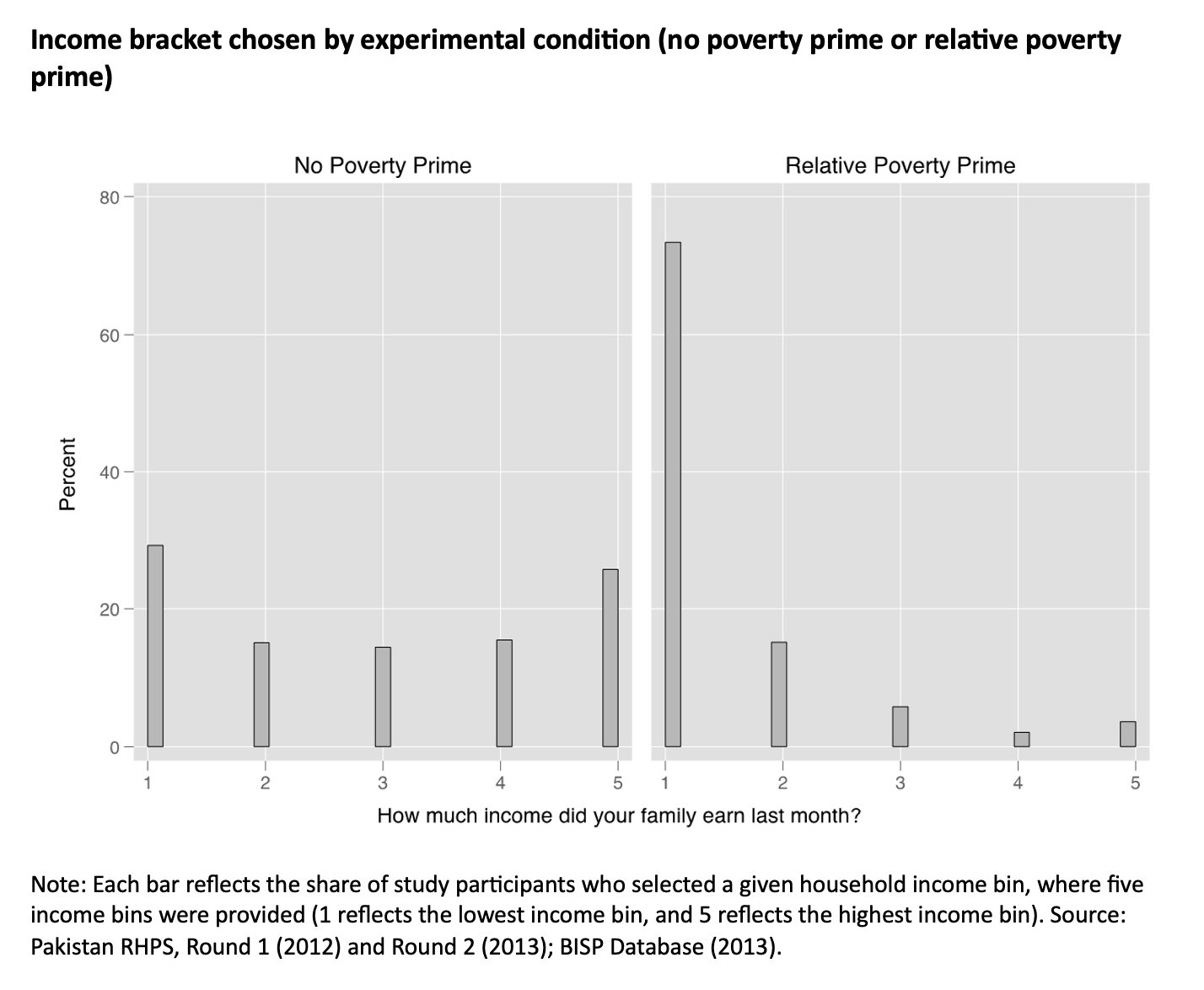

Indeed, respondents selected very different brackets depending on their randomly-assigned experimental condition—with those in the no poverty prime group being fairly evenly spread out across brackets, and those in the relative poverty prime group generally selecting the lowest income bracket (Figure 2).

The priming experiment leveraged two behavioral features: (1) the fact that individuals are uncertain about the income distribution, and thus perceptions of inequality are malleable; and (2) individuals assume that the middle response in a survey is the most typical response, making it a reference point by which they assess their own reality. Those who received the relative poverty prime were thus subtly made to feel that they had less than they should, whereas the non-poverty primed individuals were not. This priming experiment has been validated in other studies conducted in Nepal, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, and the United States (Fair et al. 2018, Haisley et al. 2008, Kosec et al. 2021, Mo 2018).

Figure 2

Results

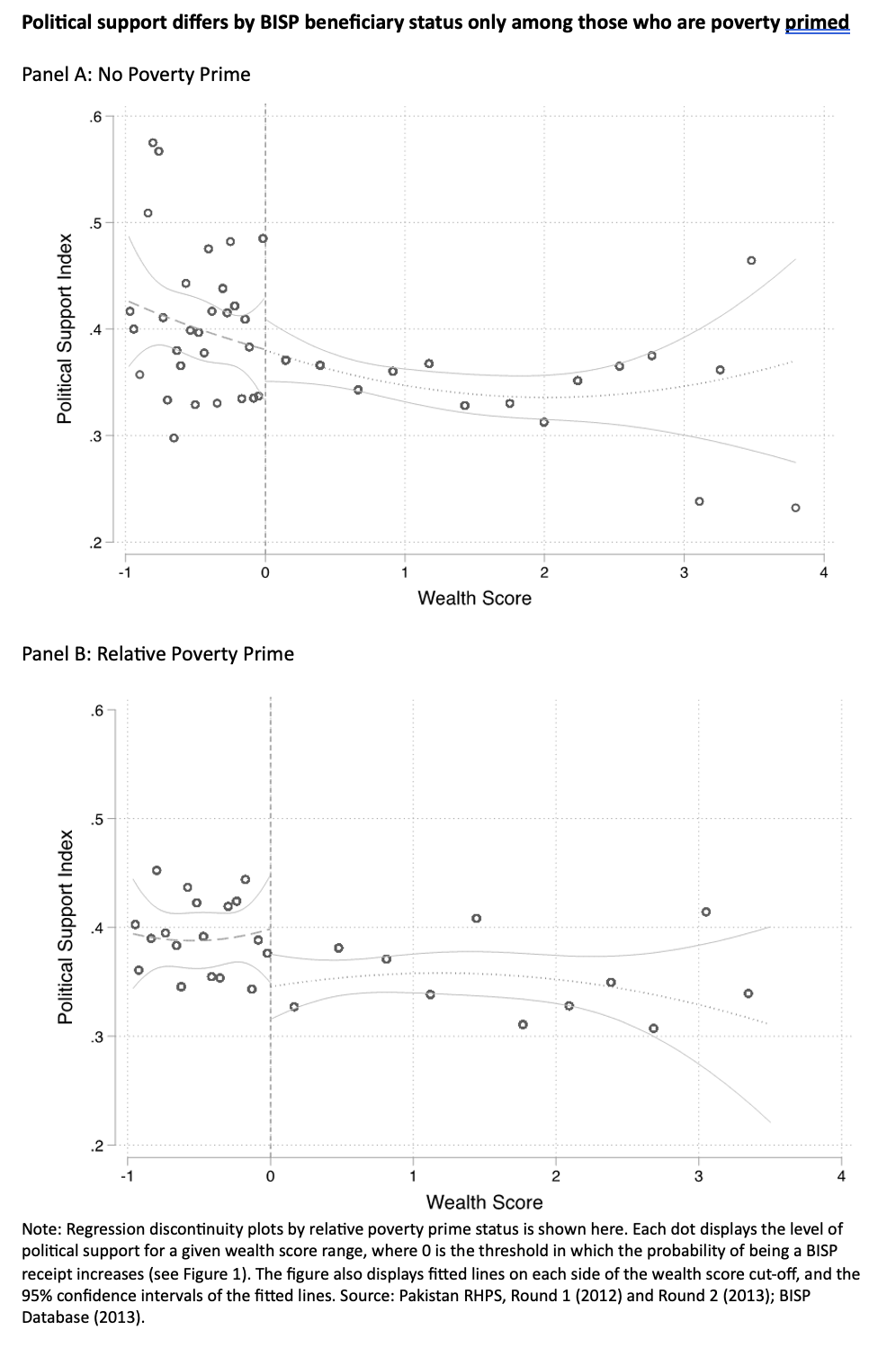

Surveying citizens between one and four years since they got their first transfers, we demonstrate that when feelings of their relative poverty are not made salient (due to being in the non-poverty primed group), citizens only minimally reward government for the program in terms of higher political support (Figure 3, panel a). But, when feelings of relative poverty are salient (due to being in the poverty primed group), beneficiaries have significantly higher political support than do non-beneficiaries (Figure 3, panel b).

Figure 3

When we looked carefully at why there were larger differences between beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries when their relative poverty was salient, we found two dynamics at play. First, considering beneficiaries, we found that feeling relatively poor caused them to feel modestly more positive (1.7 percentage points) about their political system and leaders (this suggests that feeling relatively worse-off is not unambiguously bad for engendering political support among social protection recipients). Second, examining non-beneficiaries, we found that feeling relatively poor eroded their political support (6 percentage points). The magnitude of the drop in political support among non-beneficiaries was thus 3.5 times larger than the magnitude of the increase in political support among beneficiaries.

In other words, cash transfers did little to increase government support when individuals felt that their income was typical. But when individuals felt relatively deprived and thus deserving of government transfers, receipt or non-receipt of transfers really mattered. Individuals in this mindset were mildly grateful for transfers when they were recipients, but highly discontent about not receiving them when they were overlooked.

Implications for policymaking

Our research has important policy implications. Where individuals feel especially deprived—such as following negative shocks, or on observing unequal access to opportunities, education, public services, and the like—political institutions may strongly rely on social protection. Such programs modestly increase political confidence among beneficiaries. However, when thinking about their effects on political confidence, our study points to the importance of considering the program’s effects on non-beneficiaries as well. If the social protection program is not large enough to support citizens who feel relatively worse off, and hence, in need of economic assistance, the social safety net program may unintentionally foment discontent among this population.

Overall, our research illustrates the significance of a program’s eligibility criteria and targeting. If the social protection program is poorly targeted or the threshold for receiving aid is set in a way that excludes a lot of citizens who think they are at the bottom of the state’s income distribution, there is a risk of worsening overall levels of trust in the state.

Katrina Kosec is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division; Cecilia Hyunjung Mo is Judith E. Gruber Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. This post first appeared on VoxDev.

Referenced paper:

Kosec, K, and C H Mo (2023), “Does Relative Deprivation Condition the Effects of Social Protection Programs on Political Support? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan”, American Journal of Political Science: 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12767.

This work was supported by the CGIAR Trust Fund and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).