Public investment has gained importance in development in recent years. In the Malabo Declaration on African Agriculture and CAADP from 2014, heads of state and government of the African Union recommitted to uphold the target of allocating 10 percent of total spending to agriculture, as originally agreed in the 2003 Maputo Declaration. As part of the strategy to finance the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2016-2030, the role of public investment is pivotal, especially since many of the goals relate to core public services such as health and education. Comprehensive monitoring and analysis of public expenditures are key components of achieving both the goals expressed in the Malabo Declaration and the SDGs.

The Statistics on Public Expenditures for Economic Development (SPEED) is a database that can help with such monitoring and analysis. SPEED is led by IFPRI and supported by the CGIAR program on Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM). With sector-level public expenditure data on 147 countries from 1980 to 2012, SPEED is one of the most comprehensive databases on public expenditure. Sectors include agriculture, communication, education, defense, health, mining, social protection, fuel and energy, transport, and transport and communication (as a group). SPEED data are compiled from several sources, mainly the IMF, World Bank, EuroStat, and national governments (ministry of finance, statistics bureau, accountant general’s office, and central banks). Since its launch in 2010, SPEED has been publicly available for use in research and policy analysis to help generate evidence on the linkages between different types of public expenditures and development outcomes. Evidence from this kind of analysis is important in policy discussions on efficient allocation of public resources. To get a better sense of SPEED’s role in research and the evidence that has been produced to date* by using SPEED, this blog post provides an overview of the literature that has drawn on SPEED and has been published online.

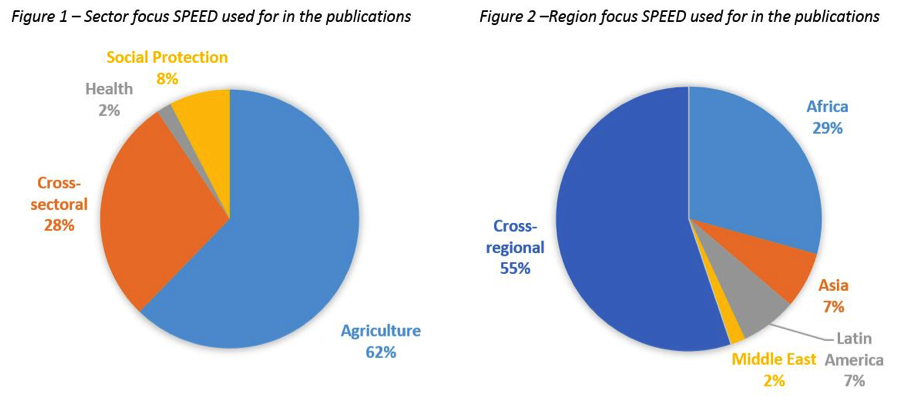

From 2010 to 2016, SPEED has been cited at least 60 times (based on Google Scholar citation). These include 17 journal articles, 15 reports, 3 books, and several discussion papers. Journals include some of the most highly regarded within their respective field, such as Agricultural Economics, the American Political Science Review, the European Journal of Development Research, Food and Nutrition Bulletin and World Development. Reports using SPEED include those issued by FAO, IFPRI, the Inter-American Development Bank, UNDESA and the World Bank. A large number of published discussion and background papers have also used SPEED, suggesting new journal articles will soon come out. To assess in which sectors and regions SPEED has had the most added value, figures 1 and 2 (right) provide information on the sector and region focus of SPEED use in publications. In terms of sector focus, the bulk of the publications was on agriculture, 28 percent was cross-sectoral (e.g. comparing spending in public education, agriculture, public health, transport and communication and social protection), and the remainder focused on health or social protection (figure 1).

Since data availability is generally better for larger public sectors, such as education and health, the relative focus on agricultural spending could imply that SPEED’s largest added value, in terms of sector-specific access to public spending data, has been within agriculture. As a reflection of the comprehensive country coverage of SPEED, more than half of the publications used SPEED for cross-country and cross-regional analysis. Africa was the most common regional focus, with nearly a third of the publications using SPEED’s Africa data solely—see figure 2, indicating that SPEED may have contributed to data availability in the region. Use of SPEED for country-specific analysis was not as common. Some of the countries include Ethiopia, Ghana, and Guatemala. Although SPEED lends itself well to country level research thanks to expansive sector and year coverage, country specific studies may be more interested in sub-national data or in other ways more detailed data.

SPEED has been used both to generate descriptive analysis on the current state of affairs in the different types of expenditures, and to conduct econometric analysis. With respect to descriptive analysis, for example, several of the publications assessed compliance with development targets and goals (e.g. CAADP and the MDGs).

With respect to non-descriptive analysis, these involved mostly studies on three general topics:

- The relationship between spending and growth or productivity. Thapa, et al (2015), for example, use SPEED data on Bangladesh, Nepal, Laos, and Cambodia to assess how agricultural public expenditure affects agricultural and GDP growth; they find a positive relationship. Focusing on Malawi, Musaba, et al (2013) find a positive effect of agricultural public expenditure on growth, but a negative effect with respect to spending in other sectors. Total government expenditure is found to be an important determinant of economic growth in Ethiopia by Zerihun (2014). Regarding the effect of public spending on productivity, Allen and Ulimwengu (2015) find a positive effect of public expenditure in health on productivity of agricultural labor inputs, whereas Shittu, et al (2014) find a positive effect of public agricultural expenditure on agricultural total factor productivity. Focusing on income inequality, Ceriani and Scabrosetti (2011) find that public expenditure on social protection reduced income inequality in developing countries.

- The determinants of government spending. Doyle (2015) and Acevedo (2016) both use SPEED to assess the effects of remittances on public spending in developing countries. Doyle finds that remittances have a negative effect on government expenditure on social protection. Acevedo focuses on education, health and social protection spending taking into account regime type, and finds a negative effect of remittances on public health spending in autocracies, but a positive effect in intermediate and democratic regimes.

- The composition of public spending. Lowder, et al (2012) use SPEED and other datasets to look at who invests in agriculture in low- and middle-income countries and finds that on-farm investment is four times larger than government expenditure in agriculture. Yu, et al (2015) examine trends in, and composition of, public expenditures in global regions and find that the developing world, especially Asia, is catching up to the developed world in terms of total spending. The developing world has, however, outperformed the developed in the share of total spending in investments in productive sectors such as agriculture and infrastructure.

It is clear from this review that SPEED is a useful tool for researchers seeking to better understand public spending—both in terms of the political economy of resource allocation, as well as the impact of spending. SPEED has also been valuable for analysis of the sectoral composition of public expenditures and the financial role of the government in specific sectors. It has allowed users to analyze these and several related policy questions across multiple years and countries, creating robust models and evidence, and adding much needed knowledge on the function of governments in different social, economic, political, and agro ecological contexts.

For further information about SPEED, see here.

*Note: Google Scholar was used to collect literature citing SPEED. The literature in this review was collected up until July 7th 2016. Any material published after that date or that is not accessible through Google Scholar may not be included in this review.

Alvina Erman is a Senior Research Assistant at IFPRI.