India’s import demand for edible oils has been significant over the past decade, with imports averaging $11.6 billion annually. In 2021, prior to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, India imported a staggering $17.1 billion of edible oils (Figure 1), dominated by palm oil ($9.6 billion), soybean oil ($4.8 billion), and sunflower/safflower oils ($2.4 billion). Interestingly, these three oils accounted for an impressive 65% share of India’s total merchandise imports from Nepal—a country not generally known for its edible oils production—in 2021, amounting to an export value of $865 million, approximately 9% of India’s edible oil imports, fifth overall among major suppliers.

Figure 1

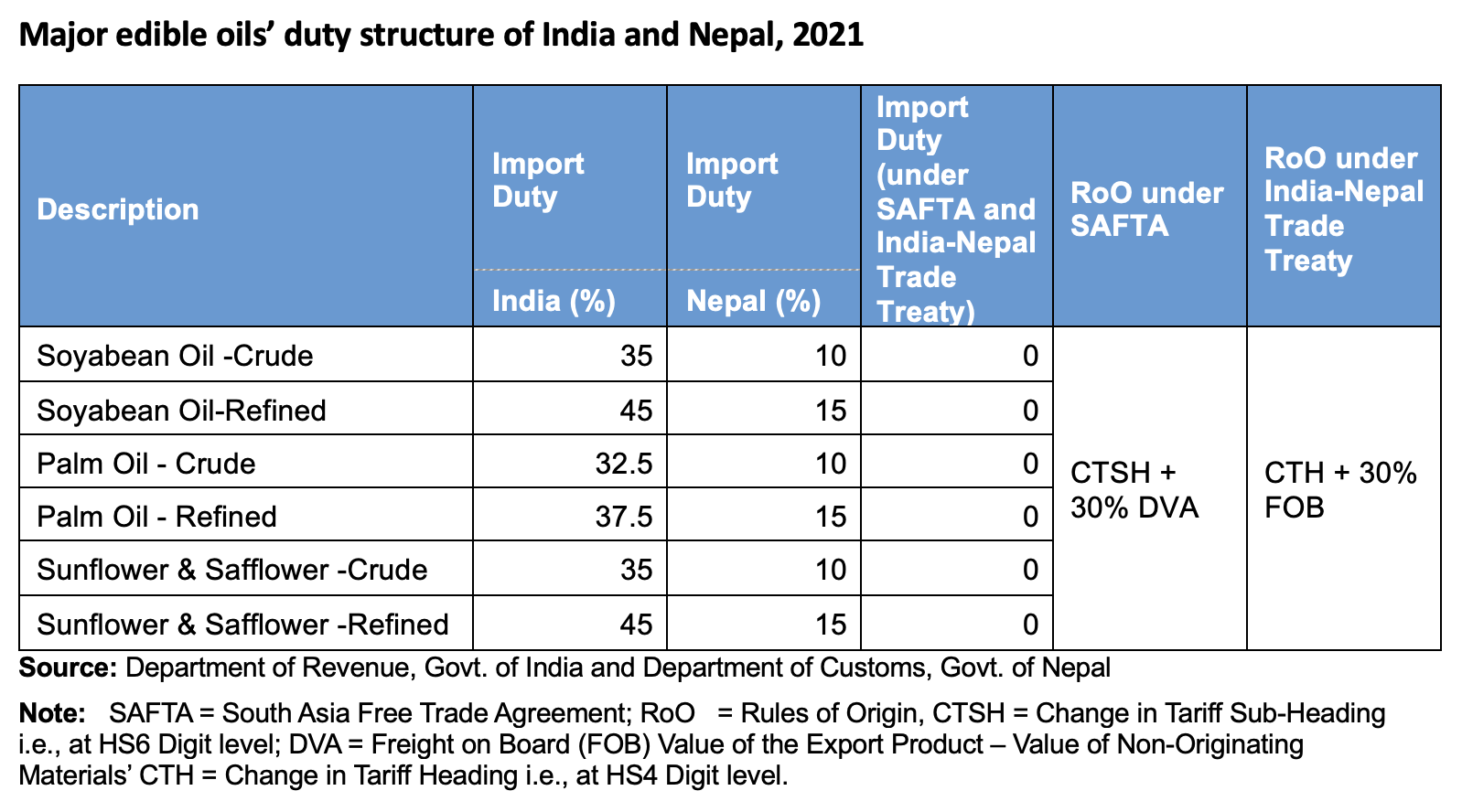

This pattern of substantial imports of edible oils to India from Nepal emerged only recently, in 2018, thanks largely to regional free trade agreements—imports from Nepal enjoy zero duty benefits under the South Asia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) and India-Nepal Trade Treaty. India, meanwhile, places significant tariffs on edible oil-producing countries, including Indonesia and Malaysia for palm oil, Argentina and Brazil for soybean oil, and Ukraine, Argentina, and Russia for sunflower/safflower oil (Notification No. 29/2018 dated 01.03.2018/Notification No. 84/2018-Customs and No. 82/2018-Customs dated 31.12.2018). These import duties created a substantial tariff wedge—a price gap between imported and domestically produced goods—incentivizing importers to reroute their edible oils through Nepal, where they could be exported to India duty-free.

What are the trade policy implications of this dynamic for both countries, and more generally?

By first exporting to Nepal, subjecting it to some processing (refining to address rules of origin requirements), and then exporting to India under zero tariffs, importers can take advantage of the tariff arbitrage opportunity created by the policy-induced tariff wedge. This setup is akin to the operations of a Global Value Chain (GVC)—when different countries contribute a part of the production process—albeit policy-induced rather than based on the comparative advantage.

Nepal’s edible oil imports consist primarily of crude oil from producing countries (98% of imports). Nepal refines the crude oil domestically and then exports it to India. Interestingly, when examining the import profiles of both countries, it becomes clear that they share the same major suppliers of crude edible oil. This is likely because Nepal imposes lower tariffs on major edible oils than India, with duty differentials ranging from 22.5% to 30% in 2021.

Table 1

Furthermore, Nepal’s edible oil exports have significantly benefited from duty-free entry thanks to meeting rules of origin criteria under SAFTA and the India-Nepal Trade Treaty. Note that 88% of edible oils directly imported by India are crude oils, a figure commensurate with India’s large refining capacity. Consequently, increased edible oil imports from Nepal have raised concerns for India’s own solvent and oil extraction industry, given the substantial tariffs on its sources of crude oils.

About 47% of refined edible oils come from Nepal and Bangladesh duty-free. In comparison, Indian processors faced duties of 32.5% on crude palm oil, 27.5% on crude soybean oil, and crude sunflower/safflower oils (Notification No. 34/2021 dated 29.06.21).

India’s policy response

Reacting to these pressures, in September 2021 India reduced duties on all three major crude edible oils to zero; on refined edible oils, the duty on palm oil was reduced to 12.5%, and on soybean and sunflower/safflower oils to 17.5%, respectively (Notification No. 42/2021 dated 10.09.21). These reductions are set to remain in effect until March 2024 (Notification No. 65/2022 date 29.12.2022).

The trade patterns that have emerged clearly indicate that arbitrage is driving the trade flows. For instance, after India reduced its tariffs, there was an almost immediate 62% reduction in edible oil imports from Nepal, which decreased to $327 million in 2022. To further validate the arbitrage channel, we observe that imports from Bangladesh also decreased by 38% in tandem, from $251 million in 2021 to $157 million in 2022.

Before India’s tariff policy change, the Embassy of India in Kathmandu raised the issue of tariff skirting through rerouted exports with Nepal’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Nevertheless, Nepal’s edible oil exports continued unabated until the end of 2021 and subsided only with India’s tariff rationalization.

From what has happened in edible oil, some lessons emerge that can maximize welfare gains for both countries while maintaining the spirit of partnership with Nepal, an important friendly neighboring country.

Stable import policy of edible oil: To enhance the effectiveness of India’s domestic policies, such as the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme backing the food processing industry, it is crucial to ensure a stable import policy for edible oils. Responding to evolving trade pressures with frequent changes in import policies creates uncertainty for exporters, domestic processors, and refiners. Such instability can have far-reaching negative consequences for trading partners, especially within preferential trading arrangements. A stable trade policy reduces risk and volatility and enables long-term trade engagements.

Duty differentials rationalization of edible oil: India’s recent move to establish minimum duty differentials with neighboring countries led to a significant drop in India’s edible oil imports from Nepal and Bangladesh. The adjustment of exports from Nepal in response to duty rationalization underscores the role of economic forces in driving trade patterns. In the absence of formal trade arrangements, informal channels, including porous borders, can facilitate spillovers. Developing refining capacity and lowering production costs could foster greater value chain integration and lead to increased benefits through “rerouted trade.”

Abul Kamar is a Senior Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance (DSG) Unit, based in New Delhi; Devesh Roy is a DSG Senior Research Fellow; Shahidur Rashid is IFPRI’s South Asia Director, based in New Delhi.