Global overweight and obesity rates have almost tripled since 1975 and are expected to continue rising over the next few decades (Shekar & Popkin, 2020). This trend is alarmingly steeper in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to high-income countries, where the same rates are gradually declining (Ng et al., 2014, Shekar and Popkin, 2020). Obesity and overweight are major public health problems strongly linked to high prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, which are projected to have an overall cost of almost $7 trillion in the next 15 years in LMICs, placing additional fiscal burdens on already vulnerable economies (Shekar & Popkin, 2020).

Government policies influence the availability and cost of foods—what role do they play in these trends? New research from the IFPRI Egypt team shows several ways that food policies may affect rising overweight and obesity rates in LMICs. Trade policies—particularly tariffs—are strongly associated with the recent trends in obesity rates, as food trade affects the demand and supply of “unhealthy” food. In the fiscal realm, policies including food and agricultural input subsidies are also a considerable factor.

To explore these connections, we focus our analysis on how changes in food subsidies and tariff rates can explain changes in overweight and obesity rates in LMICs, and how those effects vary across household wealth quantiles.

In our analysis, we merged micro- and macroeconomic indicators for several LMICs across years. The macroeconomic data is extracted from two sources: The World Trade Organization (WTO) database for tariff rates on various food products, and the World Bank’s World Development Indicator (WDI) database for the share of governments’ expenditure on subsidies. The micro-level data come from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program which provides anthropometric information covering many LMICs.

We find that tariff rates on sugar and confectionery products and fats and oils are negatively associated with overweight and obesity rates; in other words, decreases in tariffs on those items are associated with increases in overweight and obesity. Meanwhile, as the share of government spending on subsidies—including for strategic commodities such as wheat, rice, maize, sugar, cooking oil and cereals—increases, overweight and obesity rates also increase. These findings are robust to several model specifications—suggesting that specific changes in these food policies can help curb the rising trends of obesity and overweight rates and thus NCDs in LMICs.

How do these relationships vary by wealth?

Our findings suggest that trade and fiscal policies—and potential reforms—have a greater impact on poorer households, which allocate larger shares of their income on food consumption than richer ones. As healthy food is more expensive for poorer households, they are less able to afford healthy diets and are more reliant on unhealthy energy-dense foods. Our results indicate that the relationship between tariff rates on unhealthy food and body weight is stronger for the poorest households.

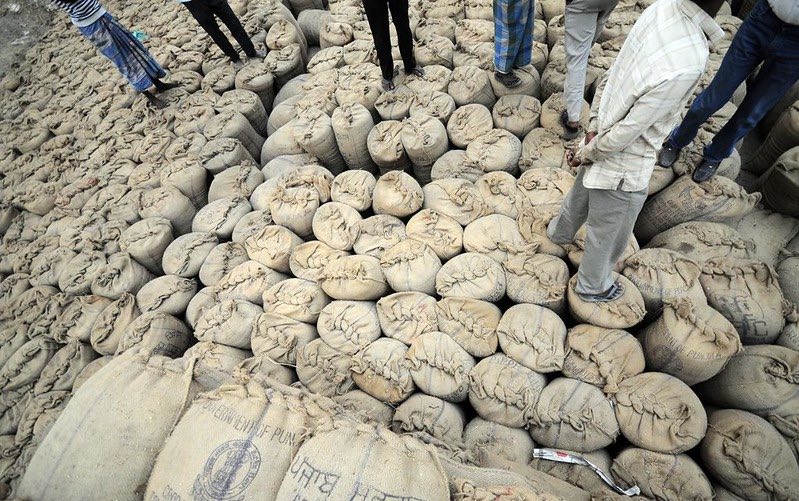

Evidence shows that LMIC subsidy program expenditures mainly go to direct subsidies including wheat, rice, maize, sugar, and cooking oil, and to agriculture input subsidies, many for staple crops such as cereals. Subsidies thus encourage the consumption of unhealthy diets in poorer households.

Conversely, these findings imply that reforming these programs can disproportionally benefit poorer households.

Overall, our results suggest the importance of combining public health policy with trade and fiscal policy reforms to address the unprecedented rise in overweight and obesity—and that LMIC governments should more actively consider nutrition-sensitive trade and fiscal policies. The robust relationship between trade and fiscal policy (tariffs and subsidies) on consumption of unhealthy food and body weight can be leveraged to combat overweight and obesity and the associated NCDs.

Reforming subsidy programs to encourage the consumption of healthier and more diverse diets (including accurately targeted cash transfer programs) can lead to reduced prevalence of overweight and obesity rates and address the double burden of malnutrition. Although reforming trade policies can be a long process requiring complex negotiations and transnational agreements, nutrition-sensitive trade agreements may help LMICs reduce potential adverse effects of trade liberalization.

Kibrom Abay is a Research Fellow and Egypt Country Program Leader with IFPRI; Hosam Ibrahim is a PhD candidate in the Department of Applied Economics at the University of Minnesota; Clemens Breisinger is a Senior Research Fellow and Kenya Country program leader with IFPRI; Ali Abdelhadi is a Senior Communications Specialist with IFPRI’s Cairo Office.

Support for this research was provided by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).