When I was child, back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I remember going to Sarett Nature Center in the southwest corner of lower Michigan, where I learned about the wonders of tropical rainforests, their destruction to make space for cropland, and the threat of global warming. Those ideas eventually provoked the question investigated in a recently published research paper that I co-authored with Alex De Pinto of the University of Greenwich (UK) and Nicola Cenacchi of IFPRI: Which danger poses the greater threat to rainforests, climate change or cropland expansion?

Here is the short answer from our modeling: Climate change is likely to be more than 2.5 times more destructive to tropical rainforests than cropland expansion at the global level between 2005 and 2050.

Where did this alarming number come from? To begin with, we looked at how much land area experienced different climates in the recent past and how that will change in the future. Figure 1 below shows combinations of temperature and rainfall and counts up how much land area experienced them globally as of 2005, the baseline for our study.

Figure 1

Source: Robertson et al, 2023

The gray-outlined box on the right side is the set of conditions best for tropical rainforests: Warm and very wet.

The orange box above it shows the same very wet conditions, but with hotter temperatures. Very few places have those climates. Those that do are roughly evenly split between rainforest, grassland, and savanna.

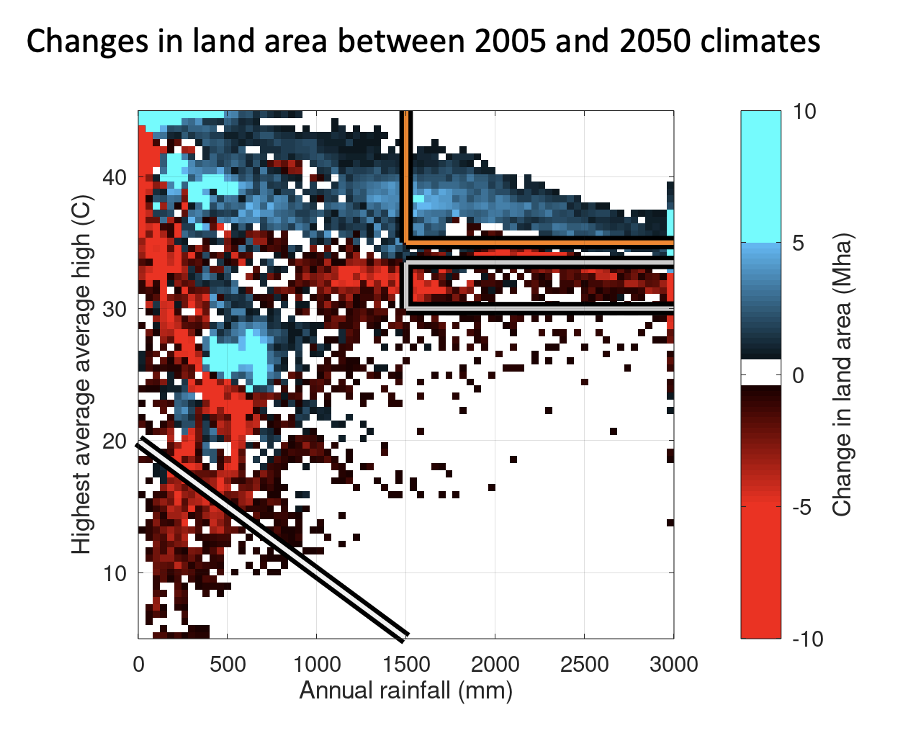

As the world warms between 2005 and 2050, the climate models show that a large amount of land area across the globe will move out of the gray/rainforest zone and into the orange/not-exclusively-rainforest zone as seen in Figure 2. Therein lies the problem: Tropical rainforest has nowhere to go to find favorable climates. Mountains provide relatively little viable land area, and that gets smaller the higher you go. Areas to the north or south of existing rainforests are generally much drier and/or hotter.

Figure 2

Source: Robertson et al, 2023

Modeling climate, natural vegetation, and cropland together

Other global-scale models have found that tropical rainforest will be lost in the future, but the size of those losses tends to almost perfectly match the projected expansion of cropland.

Our model shows dramatically larger rainforest destruction, driven largely by climate change. What did we do differently, and why?

There are two key differences in our approach. First, we allowed the model to be quite flexible and responsive to climate change for both natural vegetation and cropland placement. Second, we used climate as the primary driver both for recreating the recent past and for looking into the future. Thus, there are no initial conditions or historical geographic distributions of land that the model is anchored to, and the different land types are free to move to places with favorable climates or disappear from unfavorable ones.

Our model tracks the changing distributions of the different land types—croplands and natural vegetation—under evolving climatic and economic conditions. Then, comparing future projections with the baseline, we were able to see how much of each kind of vegetation would be impacted by cropland expansion and by climate change between 2005 and 2050.

For natural vegetation, we used a statistical model to construct maps showing the impact of climate change on different land types around the world, including forests, grassland, and tundra. The model is based on high temperature, low temperature, and annual precipitation. Further, it is split into four sub-models based on whether conditions are very wet (or not) and whether there is a distinctive dry season (or not). Those conditions are matched with land categories for the period 2000-2012 from three different datasets based on satellite imagery.

For cropland, we linked to IFPRI’s IMPACT model, which examines demand for agricultural goods and how those are produced, to determine how much cropland will be needed to produce them in the future. Then we distributed little bits of cropland to places suitable for growing each crop until we had a map of the world with the amount of cropland required by the economic model.

Results

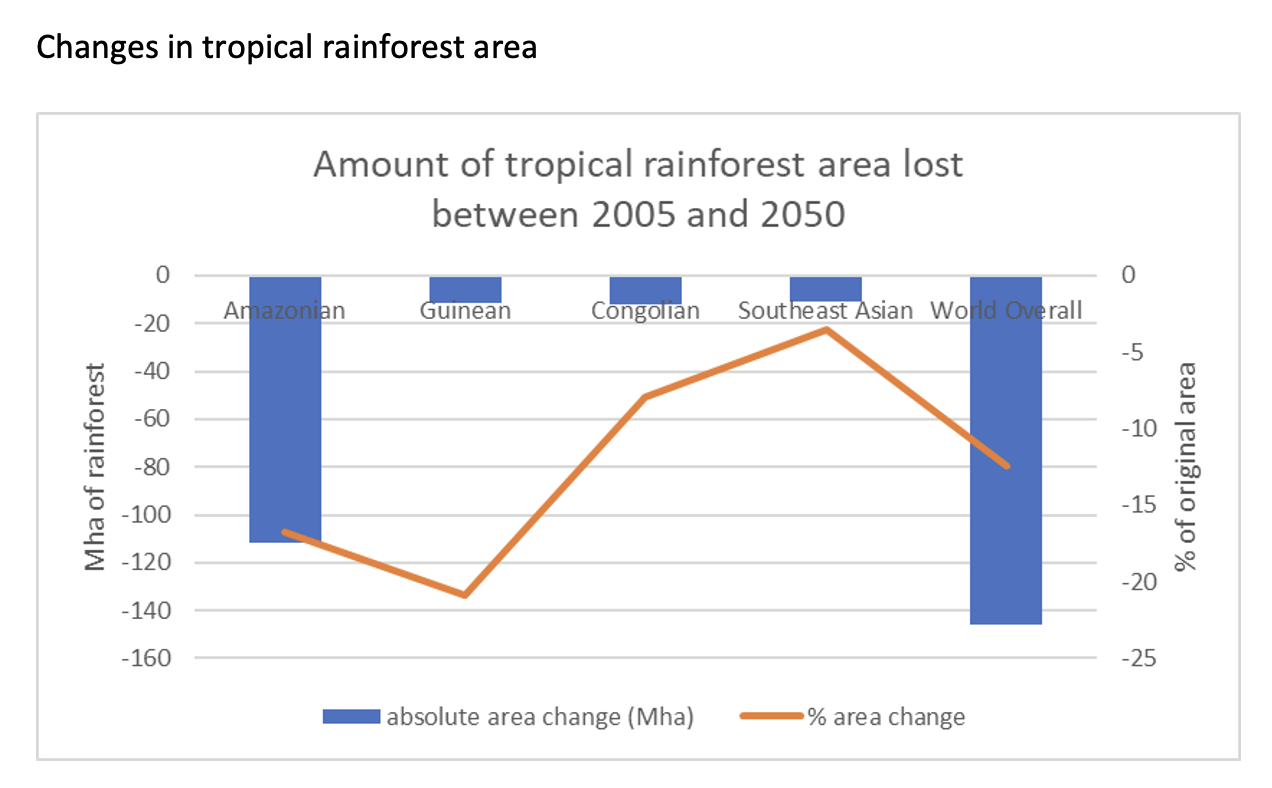

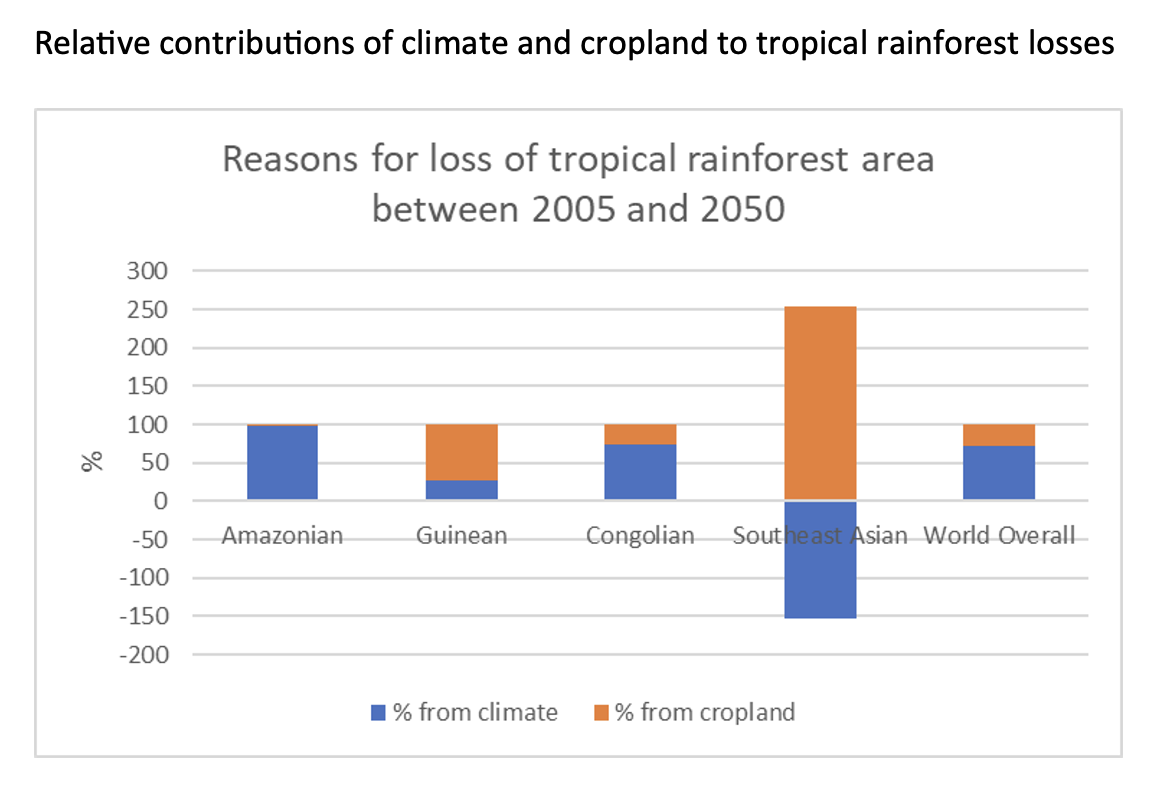

We found that globally, tropical rainforest is likely to lose about 12% of its original area in the 2005-2050 time span as shown in Figure 3. Then we examined how much of that loss could be attributed to climate change and how much to cropland expansion. Cropland expansion led to 27% of total tropical rainforest loss, while the remaining 73% came from climate change as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3

Source: Robertson et al, 2023

Figure 4

Source: Robertson et al, 2023

Taking a regional view, it turns out that the relative importance of these two impacts differs substantially across the four major tropical rainforest zones. These differences have important implications for policies aimed at protecting rainforests.

The Amazonian forests of South America show the largest absolute losses which are almost entirely due to climate. As such, in the medium to long term, avoiding the potential 17% loss in the Amazon will depend almost completely on halting climate change. There is a solid chance that the forest will deteriorate in the face of higher temperatures regardless of fences, guards, caretakers, payments, or other measures to avert deforestation.

The Guinean forests of West Africa are much smaller than those of the Amazon, yet face proportionately the largest dangers from cropland incursion (73%). Supporting farmers’ productivity along with protecting the forest directly could be very helpful in preserving these unique forests.

The hazards for the larger Congolian forests of Central Africa stem mostly from climate (74%).

Southeast Asia shows a relatively small 3% loss of rainforest area. The potential area actually increases significantly under climate change (a gain equivalent to 154% of the overall change). But this is more than offset by tremendous pressure from cropland expansion (a loss equivalent to 254% of the overall change).

The results demonstrate that climate change will play an important and direct role in determining the fate of tropical rainforests, and likely be far more important than cropland expansion. Still, research and policy efforts should focus on a more granular level on the four distinct areas of rainforest and their distinct needs. If we want to preserve the extent of rainforest area, the overwhelming dominance of the Amazonian rainforest and its sensitivity to climate requires that we take decisive action to limit global warming as much as possible. If we want to preserve the diversity of tropical rainforests, the other three zones would benefit from policies that reduce cropland expansion or redirect it away from rainforests.

Ricky Robertson is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Foresight and Policy Modeling Unit.

Funding support was received from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets; and the CGIAR Initiative on Foresight.

Referenced paper:

Robertson, R.D., De Pinto, A. & Cenacchi, N. Assessing the future global distribution of land ecosystems as determined by climate change and cropland incursion. Climatic Change 176, 108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03584-3