Agriculture plays a fundamental role in human history and has always been integral to world development; agricultural growth is an essential condition or precondition for the growth of the whole economy. Before the 20th century, agricultural growth was typically driven by input growth, especially the expansion in workforces and in cultivated land. By the end of the century, however, increasing productivity came to predominate, given the decrease in the agricultural labor force and the limited amount of arable land around the world. How can we know what drives agricultural growth? The methodology of growth accounting has been widely used to calculate the contribution from changes in inputs and the contribution due to total factor productivity (TFP, the ratio of aggregate output to aggregate inputs).

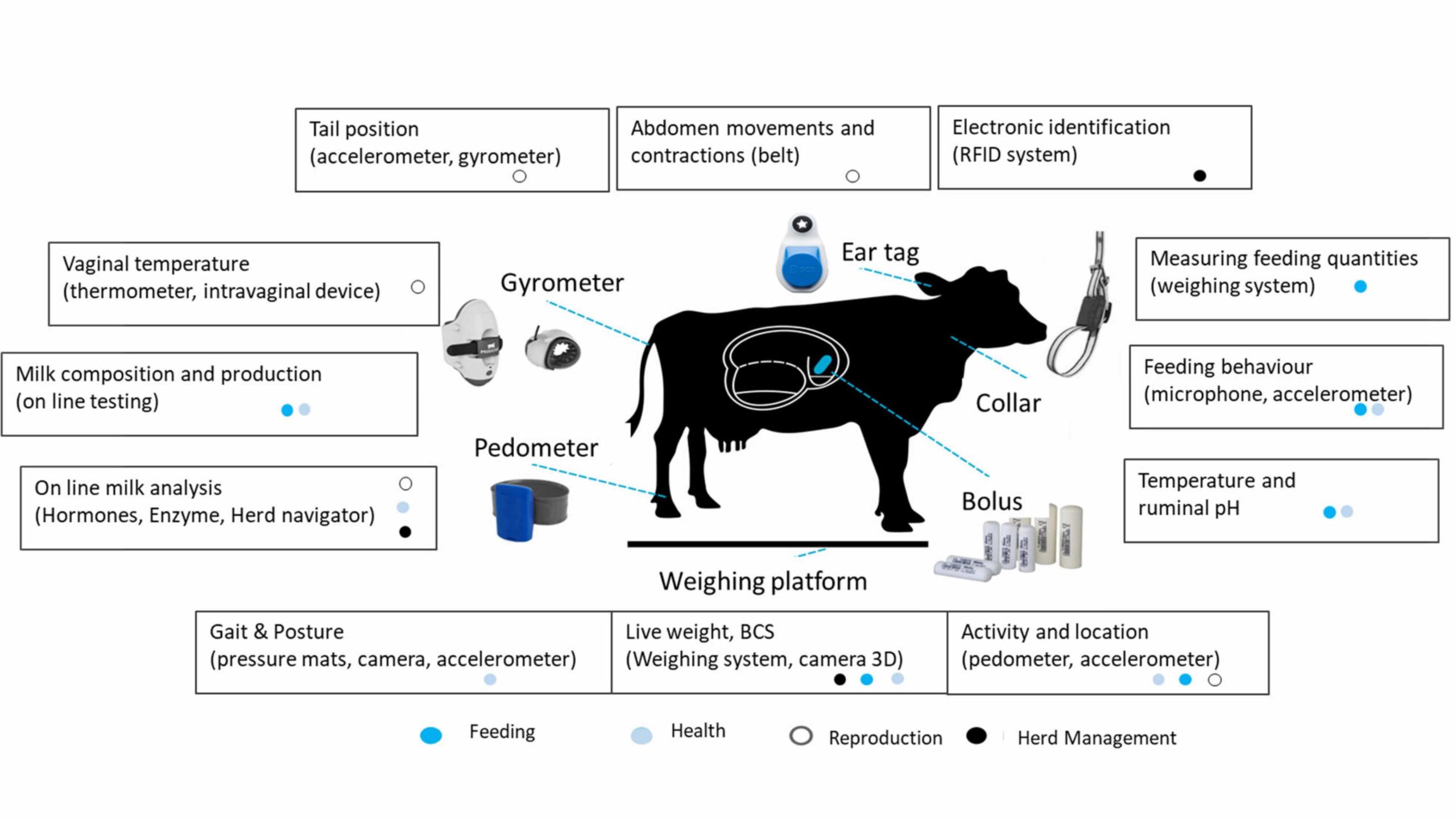

But economic drivers such as R&D and international trade also boost agricultural growth through their impact on TFP. Identifying these particular mechanisms or channels is very important. Take the effect of R&D investment on agricultural growth as an example: Egli (2008) lists some sources of agricultural productivity, including mechanization, fertilizers, more digestible animal feed, etc. All these factors can be improved through agricultural R&D spending. Hence, there are multiple pathways by which R&D investment can affect productivity and output growth.

Suppose a country has a constraint in its agricultural R&D budget: Where should we invest and how much should we invest in each field to maximize agricultural growth, fertilizer or machinery? This is an important real world decision and requires comparing the effects of R&D on economic growth through different channels. But standard growth accounting does not break out these pathways. In a recent paper, I show how a new method of growth accounting can identify these mechanisms in TFP, allowing for better decision-making.

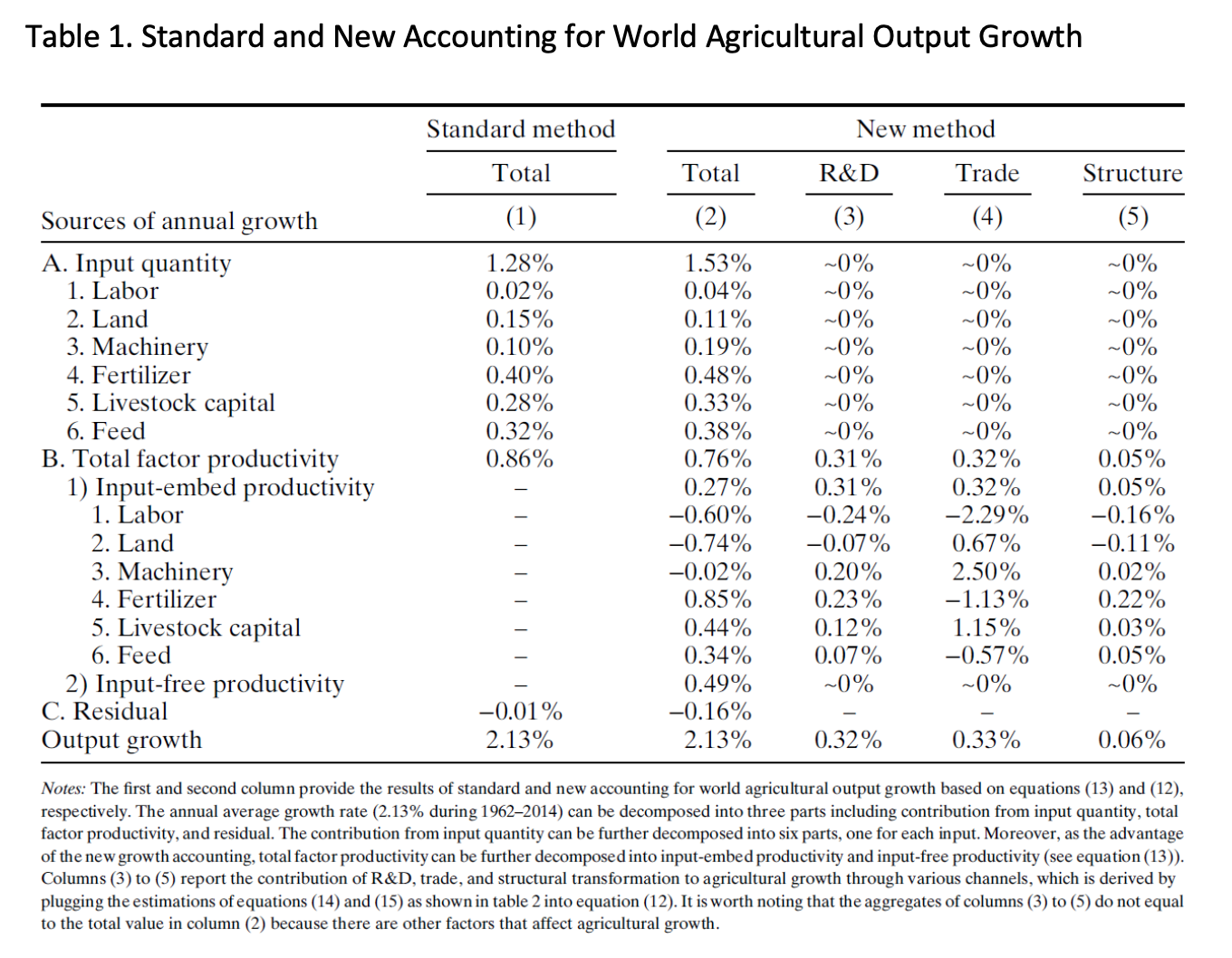

Figure 1 illustrates the difference between standard growth accounting and new growth accounting.

Source for charts: Gong (2020)

We use the new growth accounting model to investigate the impact of three economic drivers: R&D, international trade, and structural transformation (crops vs. livestock), on agricultural growth in 107 countries during the period 1962-2014. Table 1 reports the estimated contribution of these drivers to agricultural growth, along with the results of standard growth accounting. New growth accounting contributes 1.53% of output growth to input growth, 0.76% to productivity growth, and the remaining -0.16% to noise. R&D investment and international trade made great contributions to world agricultural growth, each accounting for 15% of all growth (0.32% and 0.33% in 2.13%, respectively); the most effective ways for R&D to boost agricultural growth are through fertilizer and machinery improvement, whereas the most effective ways for trade to boost agricultural growth are through land and livestock capital. Structural transformation increased the world’s annual agricultural output by 0.06%, which accounts for 3% of all growth.

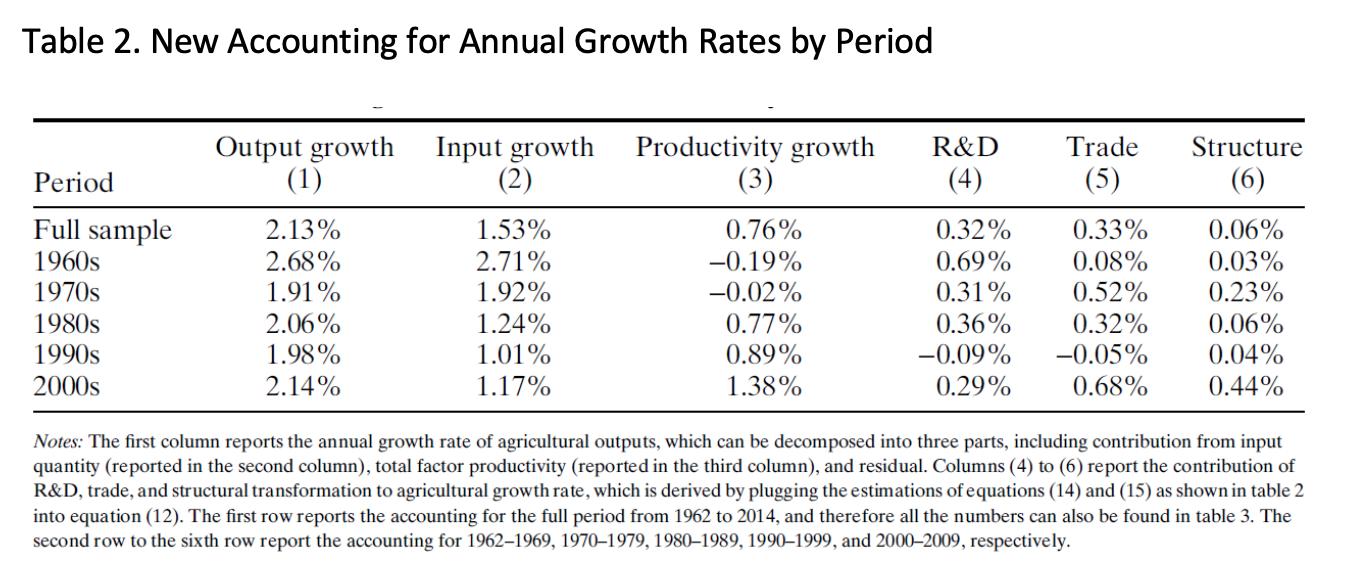

Table 2 presents the results of new growth accounting for each of the last five decades. In the 1960s and 1970s, input growth was the main source of output growth, reflecting that period’s agricultural expansion. In the 1980s and 1990s, however, productivity growth accounted for about 40% of output growth, indicating the significant technological progress and the transformation of growth patterns in the world agricultural sector. In the 2000s, productivity growth contributed more than input growth, reflecting the expanding role of agricultural modernization. Over time, world agricultural growth relied more on productivity growth than on input growth.

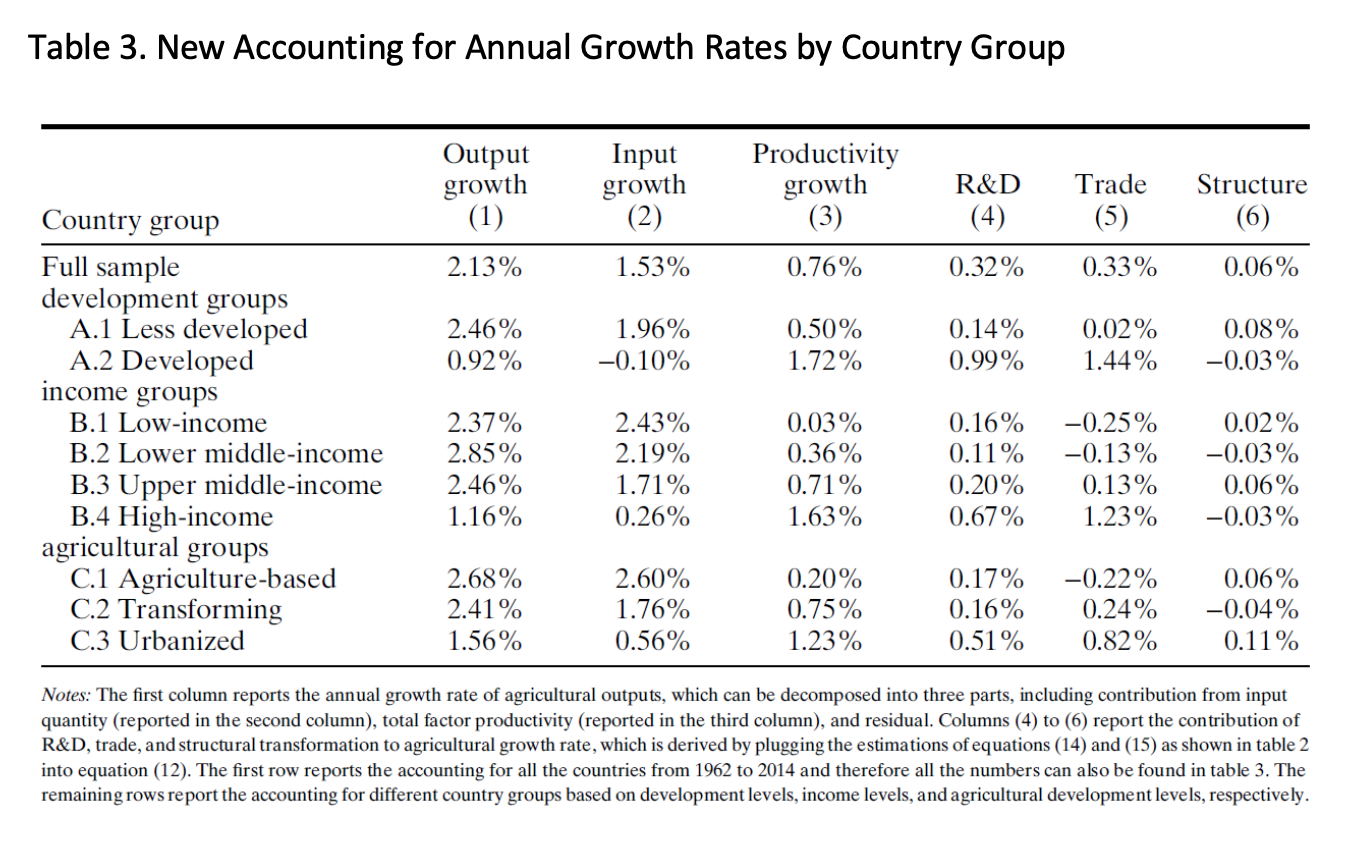

Table 3 presents the results of new growth accounting for different country groups. Comparing the results of developed countries and less developed countries, leading countries relied more on productivity growth whereas lagging countries relied more on input growth. The same conclusion can be made under the other two classifications, as high-income countries and urbanized countries achieved intensive growth, whereas low-income countries and agriculture-based countries experienced excessive growth.

Leading countries, on average, had a lower growth rate than lagging countries, and their growth relied more on R&D and international trade over the sample period. Basu and Weil (1998) point out that the input mix reflects different technologies with various production functions, so there is a limit to what countries can produce with a given mix of inputs. Taking agricultural production as an example, lagging countries using mostly labor and land, but little capital and intermediate inputs, must go through a period of increasing inputs (e.g., fertilizer and machinery), simply because a given input mix places a limit on TFP growth. The results provide evidence of the appropriate technology hypothesis proposed in Basu and Weil (1998), by showing that for lagging countries, the early phase of growth relies heavily on input accumulation; they then move to the more productive input mixes of leading countries to benefit from accelerated TFP growth.

These findings suggest that in order boost agricultural growth, lagging countries should first employ more agricultural inputs and optimize their input portfolio, then accelerate TFP growth by encouraging R&D investment and international trade. Moreover, the most effective ways for R&D to boost agricultural growth are through fertilizer and machinery improvement, whereas the most effective ways for trade to boost agricultural growth are through land and livestock capital.

Binlei Gong is a Tenured Associate Professor at the School of Public Affairs, China Academy for Rural Development (CARD), ZJU-IFPRI Center for International Development Studies, and Academy of Social Governance, Zhejiang University, China.

This post is based on the following article: GONG, B., 2020, New Growth Accounting, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 102(2): 641-661. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajae.12009

This study was carried out with support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Research Program for Humanities and Social Science Granted by Chinese Ministry of Education, the Soft Science Research Program of Zhejiang Province, and the Qianjiang Talent Plan.