The world’s agricultural monitoring systems provide up-to-date information on food production to decision makers that is crucial to global and national food security. When prices become dangerously volatile—as they did during the food price crisis of 2007-2011—these systems spread critical information quickly that can reduce the risks of market and supply upheavals.

Monitoring is now better than ever, with improved access to the latest high-resolution satellite imagery and remote-sensing based products. But fundamental gaps remain, and no system currently provides the quantitative crop area and production forecasts ideally needed for food security interventions, according to a comprehensive review by experts including IFPRI Senior Research Fellow Liangzhi You.

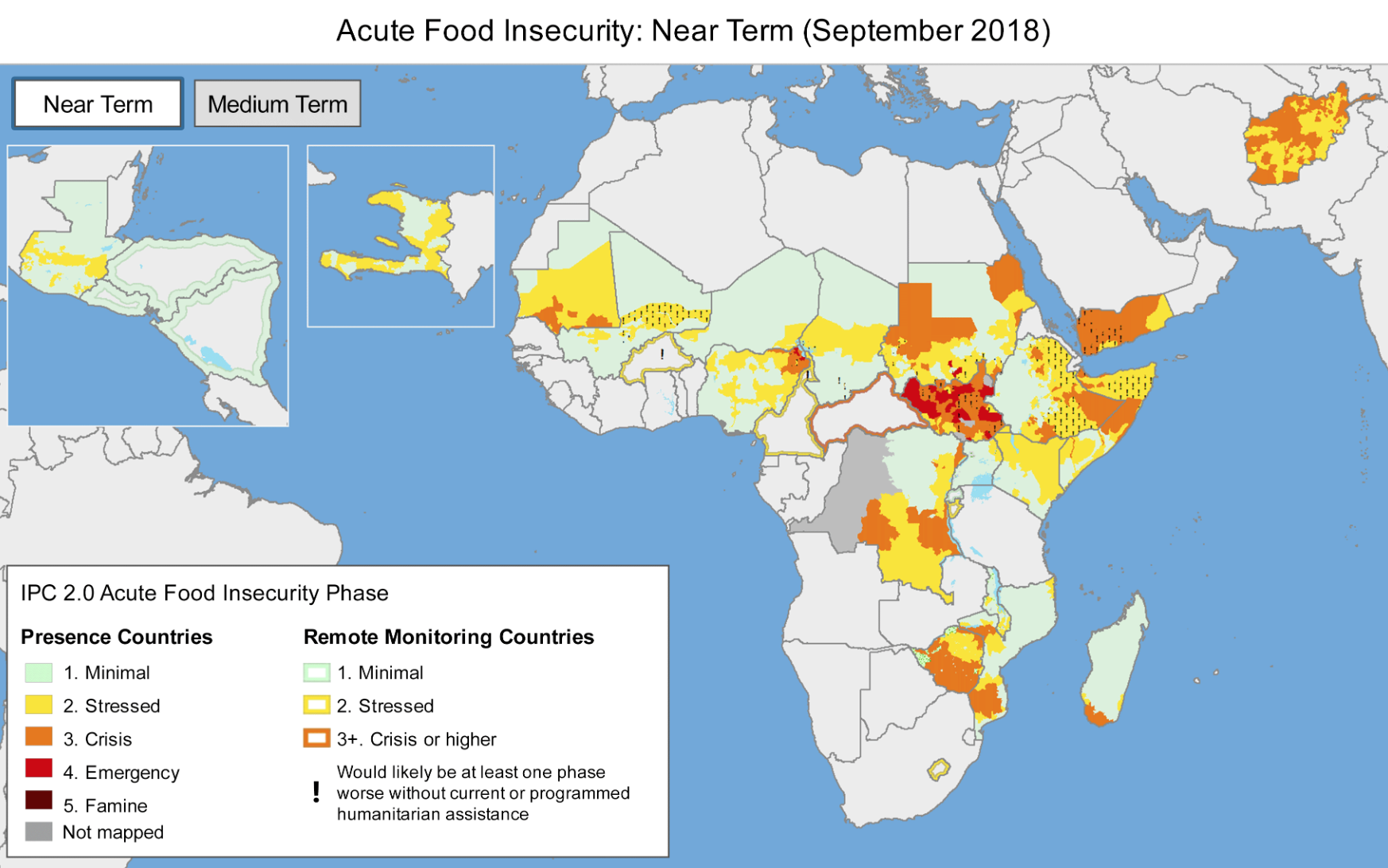

You and his coauthors reviewed the eight principal global and regional scale agricultural monitoring systems currently in operation: The Global Information and Early Warning System (GIEWS), USAID’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), the MARS Crop Yield Forecasting System (MCYFS), China’s CropWatch, the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Foreign Agricultural Service (USDA-FAS), the World Food Programme Seasonal Monitor, and Anomaly Hot Spots of Agricultural Production (ASAP).

Using questionnaires and discussions with monitoring systems staff, the study measured the gaps in input data and models used, outputs produced, the role of the analysts, interaction with other systems, and the geographical scale at which the systems operate.

Agricultural Systems

Comparison of global and regional scale agricultural monitoring systems in terms of number of sources of input data used.

They found that although each system is tailored to meet the needs of different customers, there are many similarities between the systems. For example, nearly all the reviewed systems reported that cropland maps, crop calendars, and meteorological data were their most important sources.

The most glaring gaps among the systems were found in the data used for crop calendars and crop type maps.

Crop calendars list planting and harvesting dates for the crop types in a particular area. This information is key for keeping tabs on crop conditions, estimating farming area, forecasting yields, and more. It’s used to make decisions to mobilize food aid and move commodities to market, reducing food waste. But this data comes in many different, at-times incompatible forms.

Some data comes from household surveys and censuses, some from expert opinions, and some from satellites. This lack of consistent, validated data results in poor representation of geographic diversity and variability in location and timing in sowing and harvesting dates. Maps of crop types, another important source of data for monitoring systems, suffer from a similar lack of consistent data.

The world’s crop monitoring systems would benefit from greater data sharing, the study concludes—such as a shared repository of datasets. Opportunities for more precise data collection abound. The rapid rise in the use of smart phones and social media, even in once-inaccessible rural areas, offers opportunities for farmers to self-report geo-located crops and information such as planting dates, fertilizer application, irrigation, and expected yields.

Climate change raises the risks to crop production, and these monitoring systems are increasingly critical for decision making and early warning to head off future food crises. More, and better high-quality data will help ensure they can quickly and accurately produce potentially life-saving information.

Marcia MacNeil is an IFPRI Communications Specialist.