The Uruguay Round of international trade negotiations, which started in 1986 and concluded in 1994, advanced trade liberalization and led to the formation of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture (URAA) stands out as a hallmark, since it brought agriculture—until then mostly not covered by international trade disciplines—into a rules-based framework.

An important focus of URAA negotiators at the time was domestic support provided by developed countries setting high output prices or making payments based on output. These practices produced market distortions; they incentivized farmers to produce more, which drove down international prices to the detriment of farmers in other countries. In agreeing to the URAA, countries agreed to reduce their levels of certain trade-distorting support. They also shielded some types of domestic support from reduction by negotiated carve outs and exemptions from limits under certain conditions.

A May 25 IFPRI policy seminar examined how domestic support has evolved since the URAA was adopted and why progress on further disciplines has proven to be so difficult, and offered suggestions on the way forward. It featured Lars Brink, independent policy advisor, and David Orden, professor at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University—authors of the recently published book Agricultural Domestic Support Under the WTO: Experience and Prospects—and a panel of trade experts. The event was moderated by IFPRI Senior Research Fellow Joseph Glauber.

Disciplines on domestic support

The URAA established disciplines for some types of trade distorting support, assessed through Aggregate Measurements of Support (AMSs), one for each supported product and one for non-product-specific support. For most countries, each AMS is subject to a variable limit equal to a percentage of the product’s current value of production. For other countries, a fixed limit applies to the sum of AMSs that exceed that percentage of the value of production. In both cases, if there is a government-set or administered price, market price support (MPS) is part of the current AMS. MPS is calculated by using the difference between the administered price and a fixed external reference price based on the world market price during the years 1986-88. The difference is multiplied by the quantity of production eligible to receive the administered price.

Governments can provide some support not subject to limits. Article 6 of the URAA sets out the rules for excluding certain types of domestic support from the AMS. Art. 6.5 exempts “blue box” payments made to farmers if based on fixed area and yields or on no more than 85% of a base level of production, rather than being tied to current production. Also exempt from limits are certain subsidies provided by developing countries, including investment and input subsidies, as set forth in Art. 6.2.

The URAA (Annex 2) also established an exemption for certain non- or minimally trade or production distorting support. Such “green box” payments can be exempted from limits if they meet the conditions and criteria specified under headings such as decoupled income support, environmental programs, or income safety nets. Government expenditures on general services for agriculture, such as research or infrastructure services, can also be exempted as green box support, along with expenditures on public stockholding for food security purposes and domestic food aid.

Trends in domestic support

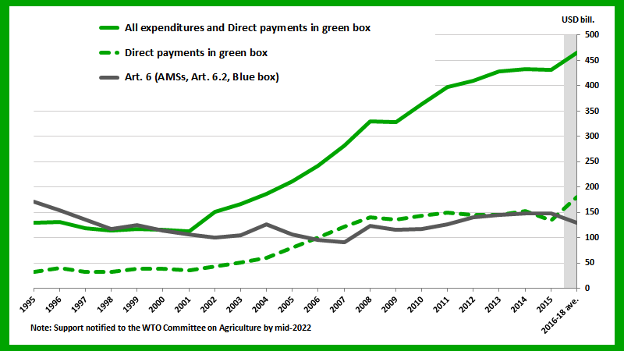

Brink outlined changes in various types of domestic support from 1995 onward (Figure 1), noting most was initially provided by developed countries. Panelist Ann Tutwiler, Senior Fellow, Meridian Institute, noted the subsequent growth of domestic support provided by China and India, and increases by other countries including Brazil, Russia and Viet Nam. Brink explained that the significant decline from 1995 to 2007 in notified AMSs was largely caused by policy changes undertaken by the European Union and Japan, whereas the increasing AMSs in subsequent years largely resulted from rapidly rising support levels in China. The largest contributors of the AMSs today are China, the EU, United States, Japan, and India.

Figure 1: Agricultural support (Art. 6) over time

Similarly, Art. 6.5 blue box support payments declined over the years, mostly due to reduced EU levels, but have recently increased as China expanded such payments.

The trend for Art. 6.2 measures shows a significant increase from 2005, largely explained by expansion of Indian input subsides, which today account for nearly 90% of all Art. 6.2 support.

Brink also showed that green box direct payments increased quite significantly from 2004 onward (Figure 2), as EU agricultural policy shifted toward such payments. China also ramped up green box direct payments. The global total has reached the same level as all Art. 6 support. The sum of direct payments and all other expenditures in the green box has grown even more substantially since 2001, including almost $100 billion from China alone by 2020. Expansion of green box support is consistent with the objective of the URAA, while some green box rules may need to be modified to accommodate policies addressing sustainability and climate change mitigation, Brink said.

Figure 2: Green box support

Challenges and possible ways forward

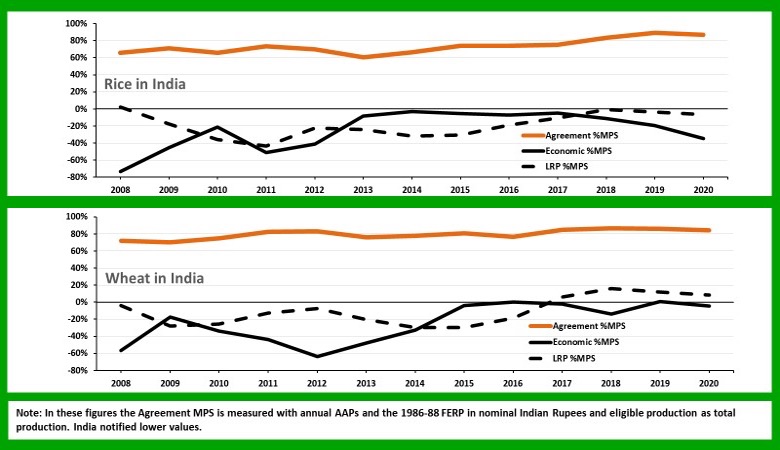

One significant issue concerns how market price support (MPS) is measured. Different approaches lead to vastly different results with very different implications, Orden explained. The legally-mandated formula for measuring MPS in the URAA uses an external reference price based for original members on prices from 1986-88; an economic measurement, meanwhile, uses current border prices in calculating MPS.

The MPS levels for rice and wheat in India, for example, when calculated under the URAA formula, have been much higher than when calculated using an economic measurement (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Measurements of market price support for India rice and wheat

Orden and Brink argued for replacing the fixed external reference price stipulated in the URAA with a reference price based on a lagged moving average of recent border prices. This, they explained, could also help to unlock the impasse on Public Stockholding (PSH).

Market price support under PSH programs is subject to a developing country’s AMS limits, but has been sheltered from dispute challenge since 2013. Many developing countries want this MPS category permanently exempted from limit. Other countries disagree. Moving to a lagged external reference price (LRP) in measuring MPS, Orden said, could provide a resolution between these positions, as it would bring the measured MPS closer to economic levels, making compliance less onerous.

Edwini Kessie, Director, WTO Agriculture and Commodities Division, confirmed that the different views on PSH are a stumbling block in the post URAA agricultural negotiations. Some members insist that PSH be considered a stand-alone issue related to food security, he said, while other WTO members would like to address it in the context of overall negotiations on domestic support, and yet another set of members insist on parallel treatment of domestic support and market access. Kessie acknowledged that positions might be too far apart to reach a concrete agreement at the 13th WTO Ministerial Conference (MC13) in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, in February 2024, but that some important progress could be made in negotiations.

Christian Lau, international trade lawyer, provided an overview of WTO disputes involving domestic support under both the URAA and the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. He explained that most of these disputes to date have addressed MPS, including a case launched in 2016 against China’s support for rice and wheat and a 2019 case against India’s support for sugarcane. While China agreed to bring its measures into compliance, India has appealed the panel findings and the dispute remains pending. Lau raised the question of whether the continued uncertainty about the meaning of core aspects of the current rules on domestic support hinders further progress toward negotiating reductions in permissible trade-distorting domestic support.

Sustainability considerations

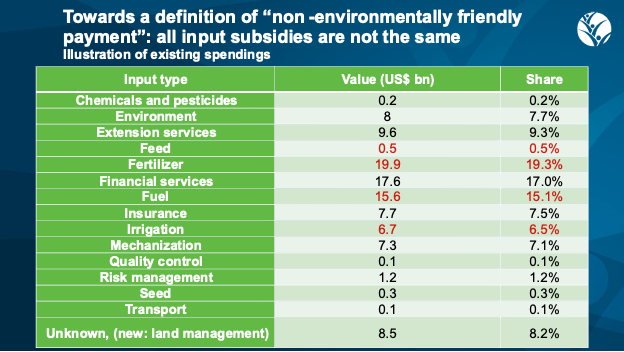

There are also calls from some WTO members for reviewing all Art. 6 support, Kessie said, including input subsidies, seen by some as being as trade distorting as output subsidies, but fiercely defended by others. Valeria Piñeiro, Acting Head of IFPRI’s Latin America region and Senior Research Coordinator, cautioned against viewing all input subsidies as the same; some make up a much larger percentage of spending, and the environmental impact of different types of input subsides also differs, she said (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Some WTO members are keen to examine whether there is a need for revised support rules given growing sustainability and climate change concerns, Kessie said. While some members question whether rapidly increasing levels of green box support are truly non- or minimally trade distorting, others call for clarifying how WTO rules mesh with the imperative to move towards more sustainable food systems.

Brink queried whether green box rules might need to be tightened or relaxed in order to clarify how WTO members can best provide support as outcome-based payments, such as for more sustainable food production or greenhouse gas reduction. Both Tutwiler and Piñeiro discussed “repurposing” agricultural support to serve climate and nutrition goals, and noted that facilitating this may require a clarification of WTO rules. Summarizing IFPRI’s work on repurposing, Piñeiro said that simply removing existing support measures would not be as impactful as repurposing the support to promote sustainable intensification— most importantly through expanding investment in R&D. Highlighting the many demands on food systems to address environmental and health externalities, Piñeiro also emphasized the importance of a sound WTO dispute settlement mechanism, considering that domestic support is often used to address market failures.

All speakers acknowledged the slow pace of agricultural negotiations, caused in large part by a lack of consensus on several domestic support issues, and growing questions about whether WTO disciplines need to be clarified to facilitate greater sustainability. Highlighting the important role that research institutions can play in clarifying complex policy questions, panelists encouraged IFPRI to delve deeper into analysis on how trade rules and shifting trade policies impact not only countries’ trade and farm incomes, but also their food and nutrition security and environmental goals.

Charlotte Hebebrand is IFPRI’s Director of Communications and Public Affairs; Joseph Glauber is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Unit.