Can foreign aid be effective only if countries have sound fiscal, monetary, and trade policies in place?

This question has been the subject of heated debates for decades. The predominant view in the donor community and in academic circles has been that foreign aid can only be effective in promoting growth and development in contexts where governments have committed to maintaining a “sound” policy environment of low budget deficits, low inflation, and openness to trade. This notion was supported by an oft-cited 2000 paper by Burnside and Dollar in American Economic Review. However, subsequent research has suggested that those findings were strongly sensitive to sample selection bias (in terms of country and period coverage) and model specification—casting doubt on the prevailing conventional wisdom.

In a recent IFPRI discussion paper, we contribute to this debate by utilizing an innovative, non-linear method to examine the aid-policy-growth relationship. This method does not impose any prior restrictions on how the variables of aid, policy, and economic growth interact with one another, allowing for a more detailed assessment of the relationship between these variables.

Methodology

We implemented a semi-parametric, cross-country model (adapted from Geng et al., 2017) that does not assume any particular a priori structural behavioral relationship between aid, policy, and economic growth. This allowed us to evaluate possible relationships between these variables over different time periods and different subsets of countries, rather than merely focusing on average effects for the entire sample of observations. In addition, the data-driven estimation approach helps avoid model misspecification of the relationship between aid and policies, on the one hand, and economic growth, on the other.

What did we find?

The left-hand panel of Figure 1 depicts the estimation results in a three-dimensional plane with aid and policy on the horizontal axes and the fitted GDP per capita growth rate on the vertical axis. Fully linear estimates (a flat plane) using the traditional linear two-stage least squares procedure (with an interaction term of aid and policy) are stacked in the figure in the right-hand panel for comparison purposes.

Here are some of the findings:

- Welfare outcomes (expressed through the fitted growth rate of per capita GDP) vary greatly for combinations of aid received and the policy environment. In particular, countries receiving more aid and having a better policy environment show better economic performance (yellow area), while those at the other end of the spectrum, with less aid and a poor policy environment, perform worse (dark blue area).

- A “sound” policy environment is associated with a better growth performance, but this is the case regardless of the amount of aid received.

- The direct relationship between growth and aid appears weak under our method. The degree of aid dependence seems to matter here. That is to say, countries receiving more foreign development assistance are already more likely to obtain a boost in economic growth when more aid is provided. This is not the case in countries receiving relatively little aid.

- A similar “threshold effect” seems to apply for the policy environment: The marginal growth effect of an additional dollar in aid tends to be substantial once a minimum degree of “policy soundness” has been established, but negligible below that threshold.

In short, the aid-policy-growth nexus is a complex one.

Much of the existing empirical evidence assumes a linear relationship between aid, policies, and economic growth. Our findings suggest this is inadequate given the indicated complexity. In effect, the linear results tend to underestimate the growth impact when aid inflows are high and policy is unsound, while overestimating growth when aid is low and policies are sound.

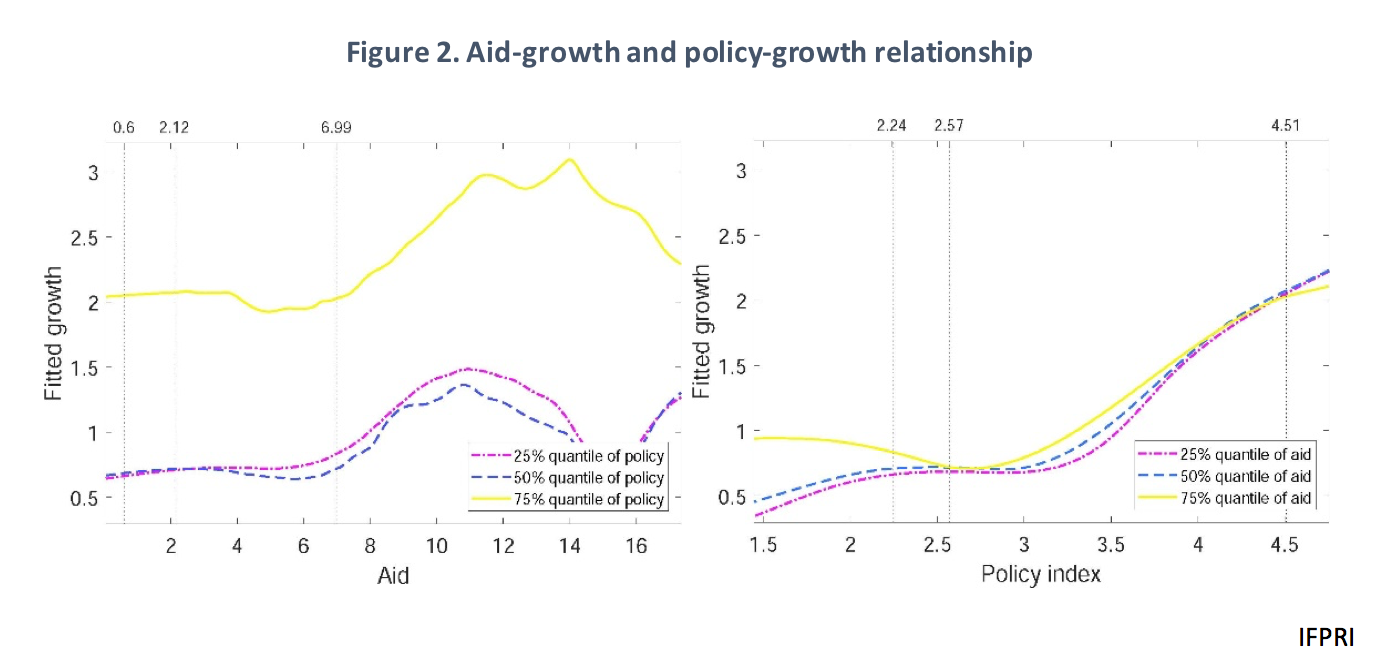

Figure 2 provides a further illustration of the estimated aid-growth and policy-growth relationship.

The left panel depicts how a country’s growth rate responds to changes in aid by slicing the surface plot of Figure 1 when keeping the policy index fixed at, respectively, the 25, 50, and 75 percent quantiles. The three vertical dotted lines indicate different quartiles of aid with their corresponding values labeled on the top axis. The figure shows that aid effectiveness seems to depend on the level of aid already being received. In other words, aid is not growth-enhancing in general; it only appears to enhance growth in countries with very high initial levels of aid dependence, that is, in contexts where aid inflows represent more than 7 percent of GDP. In terms of variation, at the 25 and 50 percent aid quantiles, a 1 percentage point increase in the share of aid inflows to GDP is roughly associated with a 0.02 percentage point increase in growth of per capita GDP. In contrast, at the 75 percent quantile, the change in growth is eight times larger (a 0.16 percentage point increase). In the latter type of context, the macroeconomic policy stance does not seem to matter in determining the growth impact of aid.

The right panel of Figure 2 depicts how a country’s growth rate responds to changes in policy by slicing the surface plot in Figure 1 with aid inflows fixed at 25, 50, and 75 percent quantiles. The figure shows that growth does not seem to increase much at low policy levels, but it does increase when the policy index is above its median value (countries included in the sample with a median policy value include Senegal, Zambia, and Pakistan). A one-unit increase in the policy index at the 25 percent quantile is correlated with a 0.08 percentage point increase in growth; at the 75 percent quantile, the same increase in the policy index is correlated with a 0.64 percentage point increase. Overall, we find a consistent positive association between the policy environment and growth, regardless of the level of aid received by a country. This positive policy-growth relationship increases in better policy environments.

Our base sample covers 61 countries and nine four-year time periods from 1970-1973 to 2001-2005. These main results generally hold across the different time periods, as well as for different measures of aid. We further find that aid’s growth impact is stronger over time (i.e., there is a lag effect of 3-4 years). Notably, however, the lag effect appears to be weaker in countries with a good policy environment and those with high levels of aid dependence.

Future work

Our results confirm the complexity of the relationship between aid, policy, and growth. Our findings help to explain the diverging results of previous studies. Importantly, the results indicate that there is no single one channel or condition which would make aid inflows, whether large or small, more growth-enhancing in the short or medium term.

Future work should continue examining the multifaceted aid-policy-growth relationship using more disaggregated data. For example, our results suggest that only when aid is very high relative to GDP can it be expected to spur growth directly. However, much development assistance is not provided with the mere objective of spurring economic growth in the short run; rather, most aid responds to needs to address humanitarian crises and to finance investments in human capital by supporting programs for education, health, and nutrition that would support economic development and poverty reduction over the longer run. Aid effectiveness thus should be evaluated much more against such longer-term development outcomes. Moreover, the “soundness” of policies, as typically defined by traditional macroeconomic factors, may not necessarily be sufficient to guarantee an environment conducive to sustainable economic growth; this would likely require broader development policies that would help remove structural bottlenecks such as low levels of human capital, poor infrastructure, and/or natural resource constraints. Our modelling approach is well suited to deepen research in this direction.

Xin Geng is an Associate Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division (MTID); Manuel A. Hernandez is an MTID Senior Research Fellow. This post is based on work that is not yet peer-reviewed.