Over 30% of rice sold in city markets in Bangladesh is refined and branded into the shape, size, and color known as miniket, which owes its popularity to its bright white color and slender grains. But miniket rice is a flawed product: It is not a true rice variety and has low levels of essential nutrients. Owing to high demand from consumers, rice vendors often sell different types of highly processed rice under that name. Processing renders miniket significantly less nutritious than other common rice types in Bangladesh, IFPRI research shows. These issues led the government to ban the sale of miniket rice in 2023.

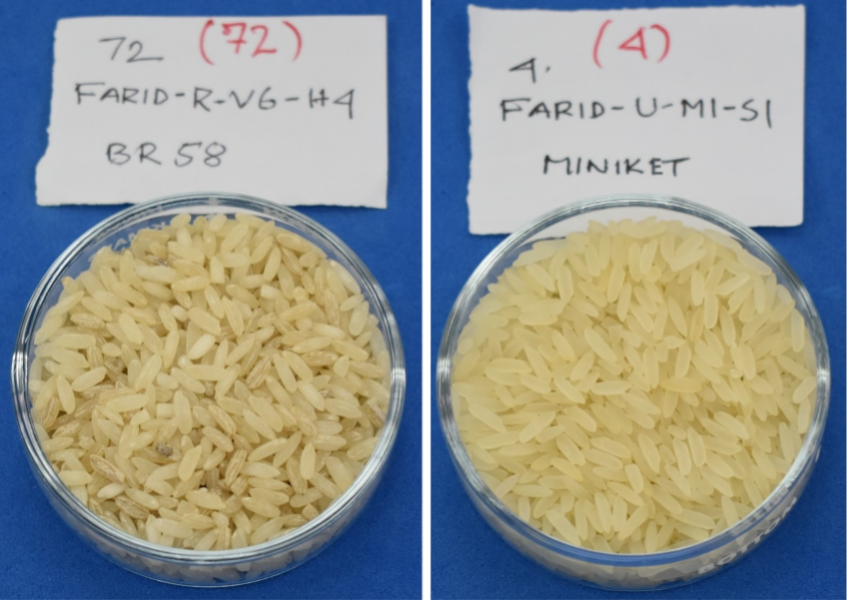

Miniket is made by taking varieties of rice with medium-slender shapes and transforming them into more slender grains using a high degree of milling (Figure 1). Because raw rice typically breaks when milled to a high degree, processors parboil the grains so they withstand breakage during milling. This process strips off edible portions of the grain, wasting food and removing essential nutrients—notably, miniket rice has up to 70% less zinc (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Rice milling differences

IFPRI

Samples of rice from Bangladesh urban markets: rice milled using a low degree of milling

(left), and high degree of milling (right).

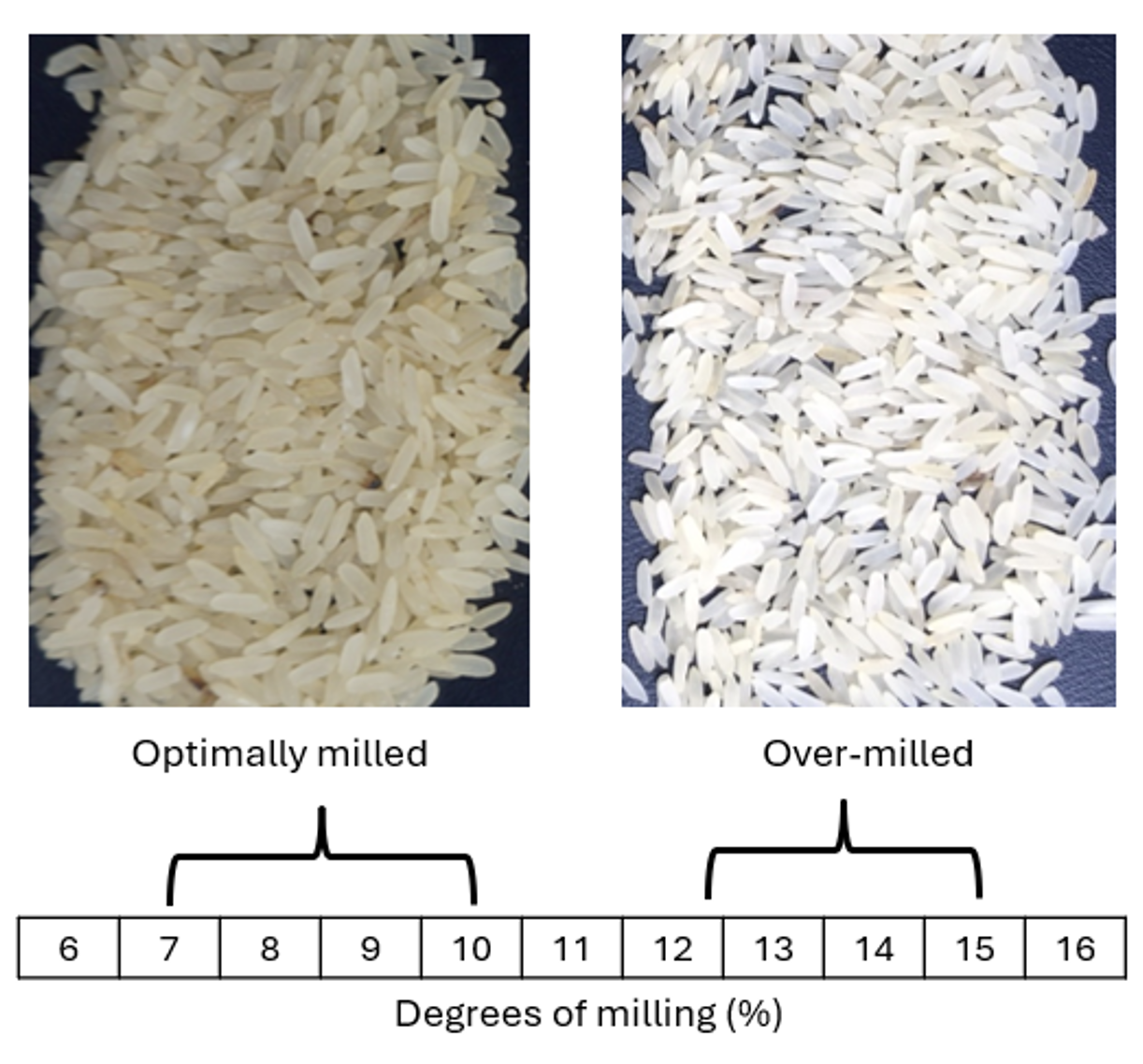

Figure 2: Degrees of milling

IFPRI

Rice milled at optimal levels for nutrition versus highly polished, over-milled rice.

The term “miniket” originates from the words mini (small) and kit (a set of supplies for a specific purpose). That name derives from 1985, when a high-yielding slender rice variety called Shatabdi was distributed in mini kits to farmers in West Bengal, India. This variety became known as “miniket” and its popularity spread among local farmers and to the neighboring border districts of Bangladesh. Today, however, so-called miniket rice sold in Bangladesh is largely fashioned from varieties such as BRRI dhan 28 and BRRI dhan 29, and is sold at a higher price than other similar (non-aromatic) rice varieties.

Data-backed policy

To study the nutritional content of miniket rice being sold in Bangladesh, between 2018 and 2021 we collected and analyzed over 400 rice samples from across urban and rural markets in five of the country’s districts. Data were presented to government officials and the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council in November 2018 showing that of all rice types sampled, miniket rice had the lowest zinc content (6.4 micrograms of zinc/gram (µg Zn/g)) compared to other common varieties like ranjit that contained up to 13.2 µg Zn/g.

Overall, the analysis showed all highly polished rice contained lower amounts of zinc than less polished rice, but that milling intensity affected zinc concentrations more than the rice variety itself.

In September 2022, the Bangladesh Department of Agricultural Extension announced a ban on the production and sale of miniket rice, and in 2023 a bill was passed to enforce the lawful production, storage, transportation, supply, distribution, and marketing of food grains—making it illegal to produce miniket rice and falsely market it as a variety.

These actions have important food system and nutrition implications. In Bangladesh, rice is eaten daily as the primary source of energy. It is a significant part of the agricultural system, diet, and culture. Nearly 38 million metric tons of rice are produced annually, with an average per capita consumption of 493 grams per day. Due to this reliance on rice, especially among resource-poor populations that lack income for, or access to, more nutrient-rich foods (like fruits, vegetables, and animal-source foods), Bangladeshis suffer from a high prevalence of malnutrition and food insecurity. Given this, it is vital for public health that nutrient-dense varieties are promoted.

According to the Global Nutrition Report, Bangladesh is not on track to meet its global nutrition targets. Nearly 1 in 3 babies born in Bangladesh are underweight, 28% of children under five are stunted, and 1 in 10 children experience low weight for their height (wasting).

A new perspective on parboiled rice

Despite the ban on miniket rice, the practice of parboiling rice—common in Bangladesh and elsewhere in the world—remains popular, presenting additional challenges for nutrition and public health.

Millers like parboiling because it reduces rice breakage. This action of soaking, steaming, and drying rice has historically been considered a means to produce a more nutritious product because it increases the amount of B-vitamins in rice. However, the process of parboiling moves zinc and other nutrients from the inner part of the grain to the outer part, exposing them to removal during milling. This practice exacerbates zinc deficiency, with consequent implications across the life-course including childhood stunting, cognitive impairment, recurrent infections, and greater risk of cardiometabolic diseases like Type II diabetes in adulthood.

More research is needed to determine country and context-specific recommendations for parboiling rice and to encourage optimal levels of industrial milling. Rice produced by local (non-industrial) mills is generally less-intensely milled.

Preliminary research indicates that excessive milling (i.e. polishing at >12% degrees of milling, as the case with miniket) should be avoided in lieu of moderate (8%-10% degrees) of milling (Fig. 2). Milling at this level results in an optimal nutrient composition of grain that consumers are willing to buy, aids nutrient intake and absorption, minimizes food wastage, and optimizes marketing characteristics like shelf life—a win-win for producers and consumers alike.

Victor Taleon is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Innovation and Policy Scaling (IPS) Unit; Zakiul Hasan is Divisional Coordinator in the HarvestPlus section of IPS; Jen Foley is a Senior Program Manager and the lead of knowledge translation for HarvestPlus. Cited research is peer-reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.

This research was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Referenced paper:

Taleon, Víctor; Hasan, Md Zakiul; Jongstra, Roelinda; Wegmüller, Rita; and Bashar, Md Khairul. 2022. Effect of parboiling conditions on zinc and iron retention in biofortified and non-biofortified milled rice. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 102(2): 514-522. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.11379