Climate change is transforming the global landscape, creating unprecedented challenges for developing countries. These challenges are particularly acute in regions where economies heavily depend on agriculture, such as sub-Saharan Africa, where climate impacts such as droughts and extreme weather are increasingly disrupting farming economies and food systems. One of the critical questions facing policymakers is how to best navigate these challenges to ensure sustainable development: Does the threat of climate change significantly undermine strategies focusing on agriculture?

A recent IFPRI study published in Climatic Change explores this issue by comparing agriculture-led and non-agriculture-led development strategies in Malawi, a country highly vulnerable to climate variability—finding that the former outperform the latter despite climate uncertainties.

This research provides valuable insights into how different development strategies can mitigate or exacerbate the impacts of climate change on poverty and undernourishment, offering a crucial perspective for policymakers in similar contexts. The approach demonstrated in this case study helps expand the set of tools available for addressing risk and uncertainty in modern policy planning.

The core dilemma: Agriculture vs. non-agriculture development

Malawi, like many low-income countries, has traditionally prioritized agricultural growth in its development plans. Despite some signs of structural transformation, the country remains mostly rural, and overall, agriculture plays a significant role in reducing poverty due to its strong linkages with rural economies. However, the sensitivity of agriculture to the impacts of climate change poses a substantial risk to this strategy. The study examines whether an agriculture-focused approach remains viable under increasing climate uncertainty or if shifting to non-agricultural sectors could yield better outcomes.

Methodology: Stochastic Dominance analysis

To address this, we employed a method called Stochastic Dominance (SD) analysis. SD analysis helps compare different development strategies by examining their outcomes under various scenarios, taking into account the uncertainty associated with each scenario. This method, although commonly used in finance, is rarely applied in policy planning.

Using Malawi as a case study, we compared climate-associated uncertainty of the two development scenarios: One focusing on intensive growth within the country’s agrifood system (AFS) sectors, and the other focusing on the growth of sectors outside the AFS (non-AFS).

We then modeled these scenarios using a dynamic economy-wide computable general equilibrium (CGE) model, which was linked to household survey data to track changes in poverty and undernourishment.

Findings: Agriculture-led development still has better poverty and undernourishment outcomes

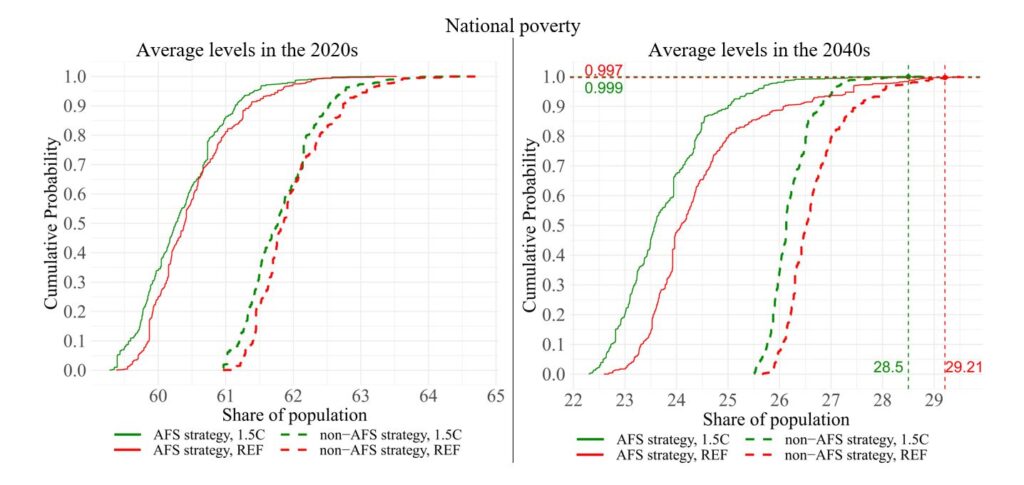

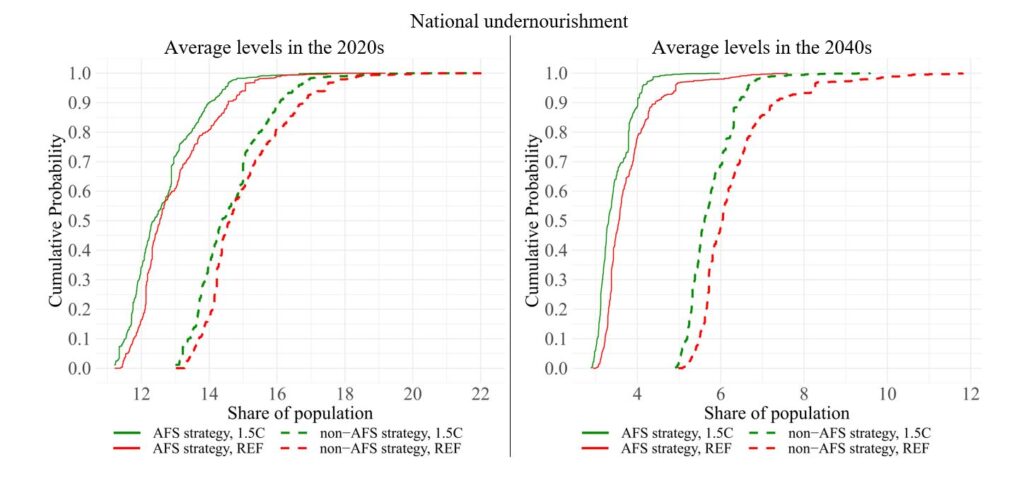

The results were illuminating. Despite inherently higher risks, the agriculture-led development strategy consistently outperformed its non-agriculture-led antagonist across almost all potential climate scenarios. Specifically, the agriculture-led growth strategy showed better poverty and undernourishment outcomes almost unequivocally even after factoring in its higher economywide climate-associated uncertainty. (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Empirical Cumulative Distribution Functions

Notes:

- Poverty and undernourishment rates are the shares of the population whose adult-equivalent daily consumption spending is below US$2.15 (adjusted for purchasing power parity) or below the minimum calorie requirement defined by the FAO.

- Two climate scenarios are considered: an ‘optimistic’ scenario (1.5C) assumes global warming is kept to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, and a ‘pessimistic’ scenario (REF) assumes no explicit climate mitigation policies are implemented anywhere in the world. Each simulation year and climate have a sample of possible 455 weathers, each of which has its own probability.

- AFS development (solid) stochastically dominates non-AFS development (dashed) across all potential climate/weather scenarios in short-term poverty outcomes (2020s) as well as short and long-term undernourishment levels (both 2020s and 2040s). The only outcome dimension when AFS development is not stochastically dominating, is long-term poverty outcomes (under very extreme worst-case weathers (0.01% and 0.03%), poverty under the non-AFS development can be lower than that of AFS.

Why agriculture still works

The agriculture-led strategy’s outperformance of the alternative can be attributed to several factors:

- Linkages to rural economies: Agriculture has stronger backward and forward linkages in rural areas, which are crucial for poverty reduction.

- Employment: A significant portion of Malawi’s population relies on agriculture for their livelihood. Boosting agricultural productivity directly benefits these households.

- Food security: Agriculture plays a key role in food security, and improvements in this sector can lead to better nutritional outcomes for the entire population.

Conclusion

Even though an agriculture-led development strategy is characterized by higher climate-associated economic uncertainty, for a country like Malawi, it remains effective for poverty reduction and nutritional improvement. Therefore, development strategies in Malawi should focus not on abandoning agriculture but on considering various options to make it more resilient to climatic shocks.

The application of SD analysis demonstrated in this study also highlights its usefulness and potential for broader use in policy planning, including consideration of various policy options within agriculture itself. By explicitly integrating risk and uncertainty into the decision-making process, policymakers, with the use of SD (and/or similar tools), should be able to make informed choices under inherently/inevitably uncertain environment such as future climate.

Cited paper: Mukashov, A., Thomas, T. & Thurlow, J. Revisiting development strategy under climate uncertainty: case study of Malawi. Climatic Change 177, 91 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-024-03733-2

Askar Mukashov is an Associate Research Fellow and Eleanor Jones is a Program Manager in IFPRI’s Foresight and Policy Modeling Unit.

This work is part of the CGIAR Research Initiative on Foresight. The authors of the study thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund. This publication was also made possible through support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation under the “IAT Policy Modeling” grant INV-018221, and from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the “Comprehensive Action for Climate Change Initiative”.