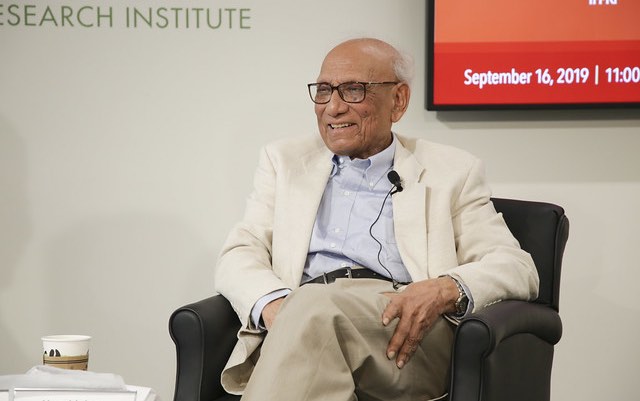

In his more than 60 years of work in international development, IFPRI Research Fellow Emeritus Nurul Islam has headed a research institute, been a freedom fighter for Bangladesh independence, served as assistant director general of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and run the first Planning Commission in Bangladesh. In an IFPRI special event Sept. 16, Islam—who also served on the institute’s first Board of Trustees in 1975—reflected on his diverse experiences and important questions in global development.

The discussion was moderated by Rajul Pandya-Lorch, director of IFPRI’s Communications and Public Affairs Division and IFPRI chief of staff.

Islam was one of the first Bangladeshis (East Pakistan at the time) to attend Harvard University, enrolling as a graduate student. “When I went to Harvard in 1951, there were only four students from South Asia,” he noted. Later, asked about the chapter of his career that he most enjoyed, he answered that teaching at the Department of Economics at Dhaka University was a highlight. “I loved interacting with the young minds,” he said. “They taught me and I taught me—it was a mutual exchange.”

Recalling his leadership roles at the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies and the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islam described the challenge of presenting research to governments. How does one communicate and translate economic research to non-economists—and will they listen?

Once, he said, he attempted to persuade a policy maker to reform input subsidies, arguing that these took away from other critical needs, such as agricultural extension. The policy maker responded that eliminating subsidies would harm middle-income farmers, one of his main constituencies, and would negatively impact crop production—even though the research showed otherwise. After months of negotiations, the subsidies were finally reduced by only a small amount—illustrating the difficulty of giving politically inconvenient advice.

Islam said he took away critical lessons from these experiences, learning to not only communicate with politicians and economists in their own languages, but also understand their perceptions of their own jobs and their responsibilities.

Asked by an audience member about the secret to Bangladesh’s success (the country is poised to become a middle-income country by 2021), Islam answered, “Bangladesh developed from one singular factor. The average Bangladeshi is extremely entrepreneurial and responds to challenges very well. The government has done a good job of staying out of the way.”

Several key development issues continue to weigh heavily on Islam’s mind. “Do we know what causes economic growth?” he asked. He noted the work of the World Bank Commission on Growth and Development, which found that there is no generic formula for bringing about development and growth. Rather, each country develops according to its own historical circumstances and political characteristics. “We know the ingredients for development, but we don’t know the recipe,” he said, quoting economist Larry Summers.

He also worries about development and democracy, especially given the current trend toward authoritarianism around the world. “There is a consensus that there is a decline in democracy. In that context, what happens to development, for better or worse? [Unfortunately, high-performing countries] are often dictatorships,” he said. “This is a subject that needs serious research.” The relationship between poverty and growth is yet another research conundrum that deserves more attention, he said. Focusing on these questions, Islam said, does not detract from the many achievements of the past few decades, including the drastic decline in death rates and incidence of disease around the world, and improvements in food supplies.

Islam also encouraged young development economists to conduct research that seeks to advance policy. For example, cross-country studies and research designs that employ diverse methodologies (vs. microstudies) can help to ensure that results are useful and can be adapted to different settings. It’s also important to reflect fully on why development policies worked or failed to work in the past. “In analyzing history, I have a serious problem,” he said. “ We have many books on ‘how’ and ‘what’ but very few books on ‘why’.”

Nurul Islam’s latest book is An Odyssey: The Journey Of My Life.

Sivan Yosef is a Senior Program Manager in IFPRI’s Director General’s Office.