Urbanization is among the major demographic shifts affecting agrifood systems worldwide. With over half of the world’s population living in urban areas—projected to reach 70 percent by 2050—cities face many challenges in providing residents with healthy, affordable food. In fact, of the 2.2 billion people experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity, three-quarters live in urban and peri-urban areas. In addition, cities in low- and middle-income countries are often the locus of diet-related noncommunicable diseases and are increasingly experiencing the impacts of climate change, including devastating floods, heat stress, and sea level rise. Worryingly, there has been an increase in conflicts in, and large-scale displacements to, urban centers, leading to massive food insecurity in places like Gaza City, Goma (Democratic Republic of Congo), and Khartoum (Sudan).

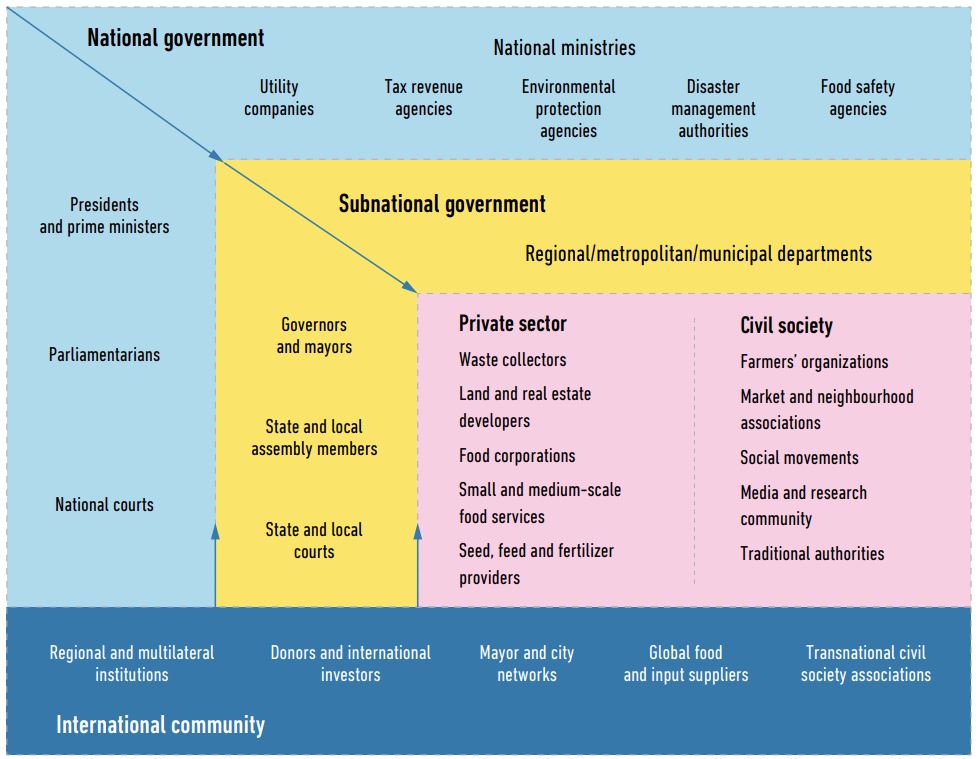

A new report launched earlier this month by the United Nation’s High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE-FSN) delves into these threats to urban and peri-urban food systems and identifies several priorities for addressing them. The report emphasizes that national food security and food system strategies have often overlooked the specific manifestations and causes of urban and peri-urban food insecurity, and that improving urban agrifood systems depends on strengthening local governance. This is a challenging undertaking given that, as highlighted in the figure below, cities are embedded in a diverse set of multilevel and multi-actor structures.

At least three main messages about urban governance emerge from the report. First, cities have very uneven capacities and policy autonomy due to differing degrees of decentralization, which refers to the legal transfer of decisionmaking and resources from national to subnational entities. Second, mandates over, and accountability for, the agrifood system also vary substantially across and within countries, and mapping of functions and coordination mechanisms can help enhance coherence. Third, decisionmakers may, due to vested interests, intentionally maintain a sub-standard status quo and thus, finding the right incentives to generate change is pivotal.

Figure: Multilevel Governance Actors Relevant to Urban and Peri-Urban Food Systems

Source: HLPE (2024). Notes: The arrows indicate the interrelationships across levels while the dash lines convey the boundaries between these spaces are porous.

Disparate capacities and autonomy at the local level

City mayors are broadly seen as leaders in tackling many emergent development efforts, from localizing the Sustainable Development Goals to the C40 initiative and the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. Yet, due to varying decentralization processes, they are operating in extremely diverse contexts. For instance, most mayors in Latin America are directly elected executives with high levels of policy autonomy while the opposite is true in much of sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, human resources vary dramatically; while there may be on average 1.4 local government staff per 1,000 inhabitants in African cities, the equivalent ratio is 36 per 1,000 in high-income country cities. Fiscal resource disparities also matter. In fact, Bolivian local governments spend 14 times more money on each inhabitant than their counterparts in Bangladesh. These differences caution against oversimplified characterizations of the powers of mayors and urban governments to tackle agrifood systems.

Uneven mandates and accountability over the agrifood system

In addition, mandates over the urban agrifood system are quite uneven both across and within countries. Local governments often have an exclusive mandate over food markets, local infrastructure, and spatial planning and zoning and may share responsibilities with national governments over food safety regulation. However, few have much authority over industrial policy, even when most agro-industry occurs in urban and peri-urban areas. Devolution of different responsibilities for agricultural, health, and environmental functions to subnational governments also varies significantly. In some cases, local governments control these functions while in others, it is left to subnational offices of national line ministries. Several policy domains, such as solid waste management, watershed management, and mass transit, require coordination across municipal jurisdictions and institutions, which becomes more complicated the larger the number of cities included in a metropolitan agglomeration.

Collectively, these issues create challenges for urban residents in determining who is accountable for the necessary services and investments to strengthen agrifood systems. Efforts to map mandates, such as that utilized in the city of Cape Town, are a useful first step in understanding where different city departments’ functions vis-à-vis the food system overlap and identifying gaps that could be addressed by engaging with partners. In Brazil, several cities have established interdepartmental mechanisms to enhance urban food security, such as Belo Horizonte’s Municipal Secretary of Food Supply, Security, and Nutrition (SMASAN). In Spain, the Barcelona and Catalan regional government created a joint Sustainable Food Office to coordinate food system policies.

Political economy (dis)incentives for reform

Many challenges to urban agrifood systems stem from government authorities’ failure to uphold the “right to the city.” This concept demands equitable andinclusive access to goods and services for all residents, not just the affluent, and therefore providing a healthy, decent life for everyone. The failure to uphold this right is often the result of distorted incentives, outdated regulations, and exclusionary spatial planning. The growth in slum housing, for instance, has been linked to corruption in land allocation and broader forms of rent-seeking in urban service delivery. Crackdowns on street vending, often based on colonial era legislation, are used episodically to gain votes or appease wealthier residents. Extortion of informal food traders by politically-aligned cartels undermines their livelihoods and affects food prices. Water mafias in African and Asian cities can manipulate water prices during times of scarcity and electoral periods.

More inclusive, transparent, and trust-based approaches are needed to change the mindset of some local governments and stakeholders to shift these practices. Market and trade associations, sometimes in partnership with transnational networks, have helped lobby against unfair taxes and repressive actions towards informal food trade. Similarly, urban food policy councils have created spaces for voice and agency for civil society, the private sector, and government to jointly deliberate on some of these political economy bottlenecks.

Conclusions

The new HLPE-FSN report highlights that creating equitable, healthy, and resilient urban agri-food systems requires a suite of different tools, from regulations to tax, trade, and market policies, social protections, infrastructure investments, and behavior change interventions. At the same time, the report stresses that such instruments cannot be uniformly applied across urban areas. The success of such policies ultimately depends on matching them to existing urban governance structures and capacities while finding new means of multilevel coordination and addressing underlying political economy forces that stymie change.

Danielle Resnick is a Senior Research Fellow in IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance Unit, as well as a Non-Resident Fellow at the Brookings Institution. She was a member of the drafting team for the 2024 HLPE report on Strengthening Urban and Peri-Urban Agri-Food Systems, with a focus on governance.