After 14 months of escalating internal conflict, Sudan is now confronting its most severe food security crisis on record. The latest Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) report, released June 27, reveals a grim picture: More than half the population is facing acute food insecurity, with a high risk of famine in multiple regions if immediate action is not taken.

This deteriorating situation stems from an escalation in conflict and organized violence among Sudanese armed factions in the civil war that started in April 2023. In its December 2023 analysis of the situation, the IPC projected that 17.7 million people (37% of the population) could face crisis-level or worse levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 and above) between October 2023 and February 2024 under plausible scenario assumptions. Of these, 4.9 million were in IPC Phase 4 (Emergency). However, the situation has since worsened dramatically.

The IPC Technical Working Group (TWG) for Sudan has faced huge challenges in updating its assessment analysis, including security threats, lack of physical access, and data gaps in hotspot areas. Nonetheless, in March, it published an alert about the rapidly deteriorating situation and the urgent need for action to prevent famine. The new analysis, conducted between late April and early June, confirms the worst fears.

Rapidly rising acute food insecurity

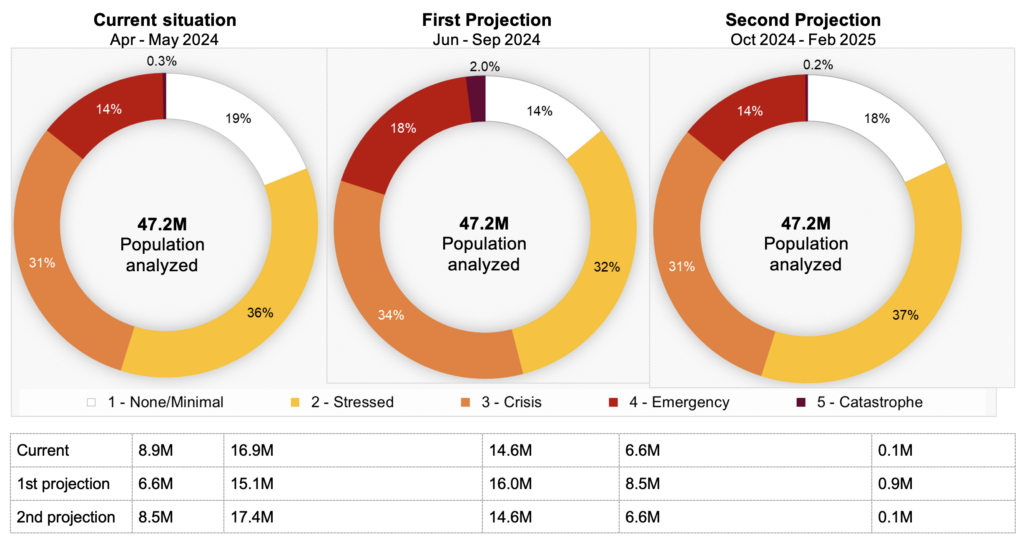

The IPC TWG estimates that during April-May nearly 21.3 million people across Sudan faced high levels of acute food insecurity, including 153,000 people in IPC Phase 5 (Catastrophe) (Figure 1). Under plausible scenario assumptions, the IPC projects that between June and September, the number of people facing crisis-level acute food insecurity will rise to 25.6 million, a 45% increase from the previous projection period (October 2023-February 2024). This scenario anticipates:

- Ongoing conflict, particularly in North Darfur, West and South Kordofan, Khartoum, and Al Jazirah states, leading to increased displacement, with heavily populated southeastern states also being affected.

- Economic shocks will persist due to conflict-related disruptions, resulting in a contracting economy, rising inflation, and below-average food production.

- Market disruptions, particularly in key trade hubs, will exacerbate food shortages and price hikes.

- Humanitarian access will remain restricted, especially in conflict-affected areas, while anticipated above-average rainfall may cause flooding, further complicating food security but offering some agricultural opportunities in accessible regions.

- Fourteen areas (localities of residents and clusters of internally displaced people and refugees) in nine states face an elevated risk of famine during the same period. Greater Darfur, Greater Kordofan, Al Jazirah states, and parts of Khartoum are the most affected areas.

- The IPC further projects that there could be some improvement in food security conditions during the harvest season from October 2024 to February 2025. As a result, the total of those facing crisis-level or worse food insecurity could fall to about 21 million people, but still leave 109,000 people in IPC Phase 5 (Catastrophe).

Figure 1: Acute Food Insecurity in Sudan, in three scenarios

High concentration of hunger in Al Jazirah, Khartoum, and Darfur

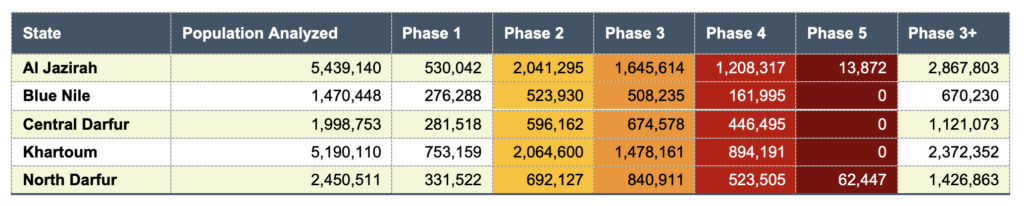

Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of affected populations by IPC Acute Food Insecurity Phases across key states in Sudan projected for June-September. Most acutely food-insecure are found in Al Jazirah and Khartoum, which are among the larger regional populations analyzed. North and Central Darfur also show high numbers in IPC Phase 4 (Emergency) and North Darfur is home to over 62,000 people facing famine-like conditions (IPC Phase 5).

Table 1: IPC Acute Food Insecurity Phases for Key States (June – September 2024) in number of people

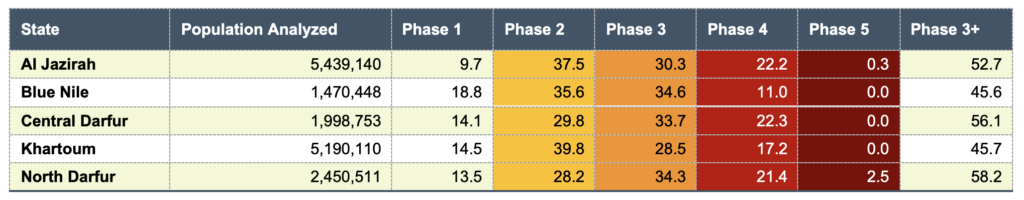

able 2 shows the prevalence of IPC Acute Food Insecurity Phases for the same key states from June to September. In relative terms, acute food insecurity is severest in Al Jazirah and North Darfur, with over half of their populations in IPC Phase 3 (Crisis) or higher (respectively, 52.7% and 58.2%). Central Darfur also demonstrates significant distress, with 56.1% of its population in IPC Phase 3+. Particularly critical is North Darfur, where almost 60% is in IPC 3+ and with 2.5% of the population facing famine-like conditions (IPC Phase 5). Overall, the high concentration of acute food insecurity underscores the dire humanitarian needs in these regions, and the urgent need for targeted interventions to address the severe hunger crisis.

Table 2: IPC Acute Food Insecurity Phases for Key States (June – September 2024) in percent

Key drivers

The main driver of this rapidly worsening situation is the intensification of Sudan’s conflict and insecurity situation. The conflict has restricted movements of goods and services, disrupted markets, and hindered agricultural production and humanitarian access, thus severely reducing the availability and access to food for millions of Sudanese.

Sudan’s current food crisis is not new; it is part of a recurring syndrome of triple crises comprising protracted civil conflicts, climate shocks, and economic instability. Beside the ongoing war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the country has a recent history of severe civil conflicts, including Africa’s longest civil war (1983-2005) and the Darfur crisis (2003) among others. These have triggered economic woes, including skyrocketing prices of basic commodities, severely eroding food access for much of the population. Additionally, climate shocks such as prolonged droughts and severe flooding have devastated crop yields and livestock, with national cereal production in 2023 estimated to be 46% below levels of the previous year.

The conflict has forced the displacement of more than 10 million people. Sudan now counts 10.1 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 2.2 million refugees, making it the country with the highest number of forcibly displaced people in the world. The IDPs and refugees have lost their livelihoods and are largely dependent on humanitarian assistance. As the conflict is hampering access to such assistance, these are among the people most at risk of famine.

Economic conditions have recently worsened further. Disrupted supply chains and production capacity have pushed up already very high prices of food and all other basic necessities. In some areas of the country prices of staple commodities have tripled since May compared with the most recent five-year period average.

Can a famine be averted?

To avert a famine, a de-escalation of the conflict is needed to create better security conditions and put an end to the current disruptions in markets, supply chains and distribution channels. The IPC TWG also makes these recommendations for immediate action:

- Restore humanitarian access so that humanitarian agencies can get safe and sustained access to areas with populations most in need in order to deliver essential supplies to those in need, especially IDPs and refugees in the conflict-affected areas.

- Substantially increase the amount of food assistance and other essential supplies to prevent loss of life and support livelihoods.

- Scale up nutrition Interventions, including urgent treatments for malnutrition, particularly for vulnerable groups such as children and pregnant women.

- Support livelihoods, including distribution of agricultural inputs and creating safe zones for farming to help food production to recover and rural livelihoods to improve.

As the world watches, it is crucial for the international community to respond swiftly to avert a humanitarian disaster in Sudan. The full IPC report provides further details and underscores the pressing need for coordinated efforts to address this escalating crisis.

Khalid Siddig is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance Unit and Leader of IFPRI’s Sudan Strategy Support Program; Rob Vos is Director of IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Unit. Opinions are the authors’.