The continuing conflict in Sudan between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), underway since April 2023, is inflicting devastating impacts on the country’s economy and on livelihoods. Model estimates show that production declines across different sectors have resulted in a loss of about $10 billion to GDP—about a third—as of September.

The industrial sector, which contributed an average of 21.7% to GDP between 2011 and 2021, has suffered the biggest losses in percentage terms, projected to shrink by around two thirds by the end of 2023. Within the agrifood system, the most devastated segment has been the agrifood processing and food manufacturing sectors. Frequent violent confrontations in Sudan’s economic hub of Khartoum have halted most of country’s agri-processing operations, which are centered there. This sector makes up a large proportion of all off-farm activities, whose contribution to GDP is 14%. These disruptions have led to increases in imports of processed foods and beverages from neighboring countries like Egypt and Ethiopia. Meanwhile, the conflict also poses serious challenges to food supply chains and consumption of locally produced food across the country.

Assessing these impacts poses challenges due to the lack of comprehensive data during wartime in Sudan. To get a clearer picture, we used a brief online survey, outlined in a recent Working Paper, to investigate the impact of the conflict on the agri-processing and manufacturing sector. Data collection began in the last week in June in both English and Arabic. Eighteen firms were contacted using a snowballing approach and 15 responded. (The small sample size is attributable to the fact that many firms were unreachable online due to the active and intense nature of the conflict.)

Closed businesses, damaged facilities

The outbreak of war seriously disrupted business operations, the survey found. As a result of the combat near the Khartoum North Industrial Area, where many processing and manufacturing plants are located, responses indicated that 13% of the agrifood processing firms operating in Khartoum had permanently ceased operations, 53% had temporarily closed down, and another 20% had reduced their operations significantly as of July 2023.

Notably, some factories suffered direct damage during this period—either looted, damaged, and/or burned down. Additionally, many Khartoum-based agri-processing firms reported looting and theft in their warehouses in various regions—most often in Khartoum, El-Obeid, and Nyala states.

About 57.1% of the agrifood processing firms operate within Khartoum State only, while 35.7% are based both in Khartoum and other states. Raiding of offices, including thefts of safes and documents, has limited Khartoum-based headquarters (HQs) in supporting company activities across the country. However, companies with regional offices across Sudan have been more resilient than companies operating exclusively in war-torn Khartoum State. At the state level, 75% of firms operating exclusively in Khartoum State are temporarily closed, while an equal proportion of firms (just 29% each) with operations both in Khartoum and in other state(s) or exclusively outside of Khartoum State are either temporarily closed or operating on reduced capacity (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Kirui et al., 2023.

Impacts on employment, inputs, transportation

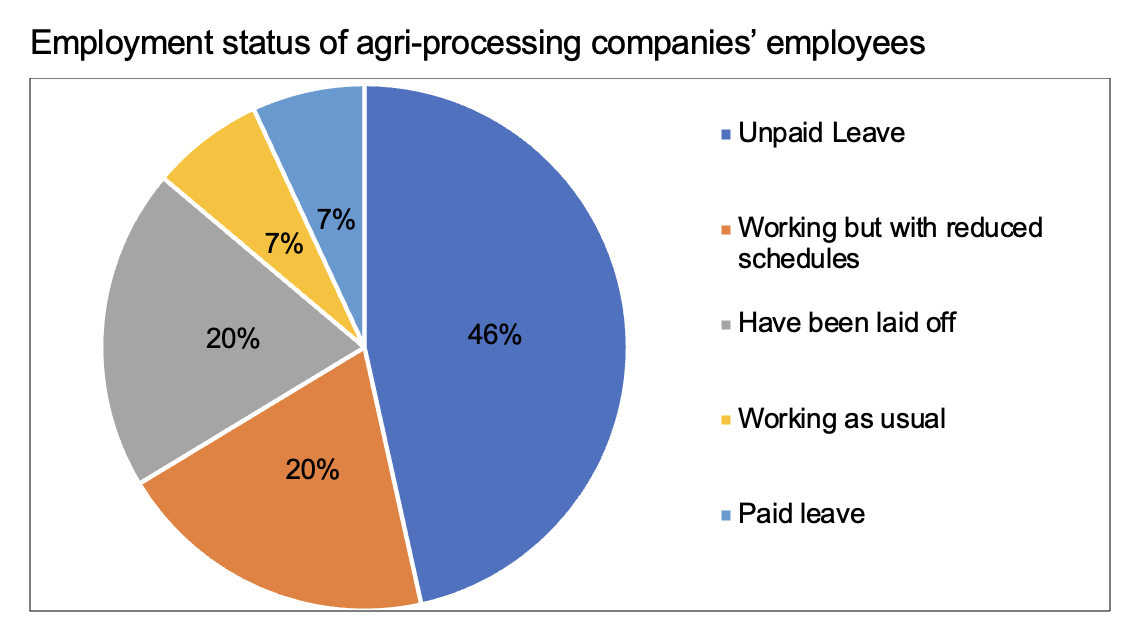

Because most of the agrifood industry plants in Khartoum provided direct or indirect job opportunities to farmers, traders, and intermediaries, their closures have had serious employment impacts. More specifically, 46% of the firms in Khartoum have put their workers on unpaid leave, while other firms have resorted to different approaches to maintain staff and/or operations—such as working on reduced schedules or completely laying off the workers (Figure 2). These strategies vary by state. For instance, while 63% exclusively operating in Khartoum placed employees on unpaid leave, just 29% of the firms operating both in Khartoum and other states put workers on unpaid leave and another 29% kept them working but on reduced schedules and reduced production volumes.

Figure 2

Source: Kirui et al., 2023.

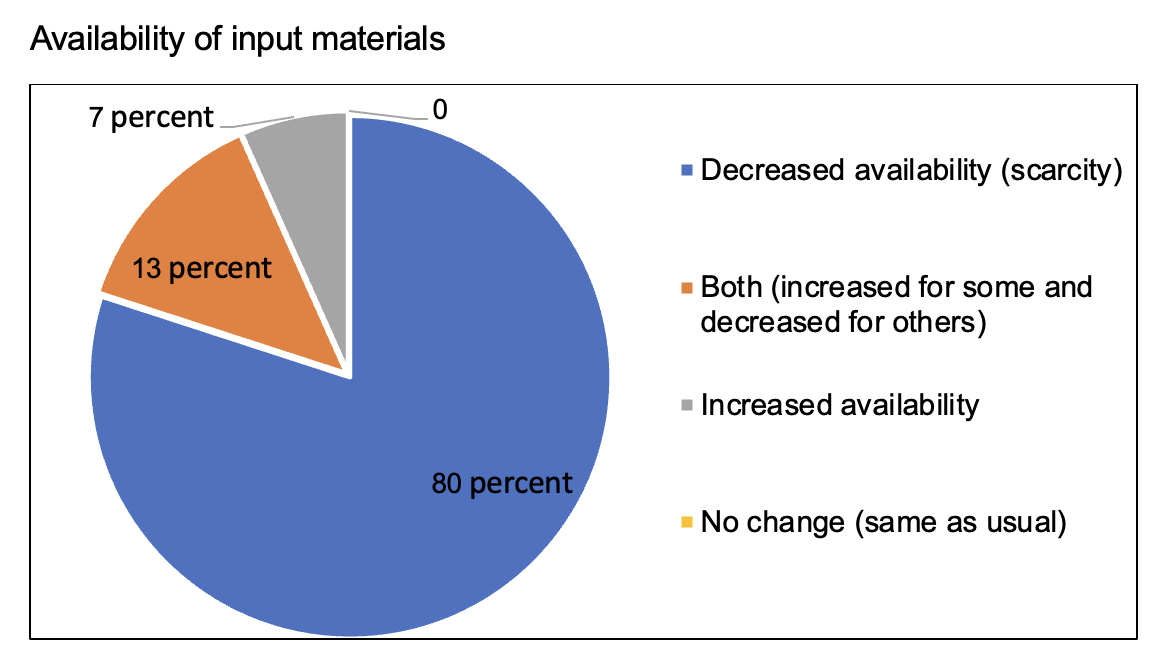

Additionally, agri-processing firms have been hit by reduced availability of material inputs, with 80% of surveyed firms reporting increased scarcity of required key production resources. This is mainly due to conflict-related transportation disruptions.

In-land trucking accounts for approximately 95% of crop and food transportation in Sudan, with 55% of the trucking services provided by individual truck owners (Abushama et al., 2023). Due to a drastic increase in transportation costs and road blockages to and from conflict states, the movement of key input materials has slowed or stopped.

Rising food imports

The importation of food and other goods (including key raw materials for processing firms) has also grown more difficult. One reason is increased demands for advance payments from foreign suppliers, even as domestic buyers face a dysfunctional banking environment. Prior to the eruption of the conflict, Sudan’s imports of foodstuffs (including wheat, vegetable oil, and other essential food products) amounted to 25.3% of the total imports in 2022. That number is likely to spike as the conflict continues to disrupt the agri-processing sector; as production falls short of rising demand, imports of processed foods will increase, as reported by our key informants. Yet importing more processed foods will not necessarily address the food security issues posed by the conflict. Food distribution across non-conflict regions continues to generate high transaction costs, while distribution to conflict regions is deemed nearly impossible due to route blockages in and out of those regions.

Figure 3

Source: Kirui et al., 2023.

Looking forward

In summary, agri-processing firms have been drastically affected by the conflict in several ways:

- The loss of material inputs and/or finished products in warehouses (due to looting and burning down of the premises).

- Physical destruction of production plants and warehouses (especially in Khartoum).

- Reduced availability of material inputs coupled with increased costs of accessing local and imported materials.

With the conflict entering its ninth month with no sign of a cessation of hostilities between the two warring parties, Sudan’s agrifood processing firms will require strategic medium- to longer- term interventions to support their operations in conflict regions. For instance, the Khartoum-centric nature of the current conflict is forcing many businesses to decentralize their operations to other states. For example, many small and medium enterprises have shifted operations from Khartoum to Gezira, Gedaref, and White Nile states, among others.

Such moves have short-term costs, including establishing business operations and building solid market structures not linked with war-torn Khartoum. But in the longer term, these changes could promote greater competition in Sudan’s economy and lead to positive decentralized development outcomes.

The revival of the agri-processing sector after the conflict would require concerted efforts from a number of stakeholders. Key among these efforts would be restoring financial services for agri-processors and agrifood importers and exporters. This will require rebuilding the functionality and operations of the Central Bank of Sudan and its technical arm, Electronic Banking Services (EBS). This would require improved infrastructure—a continuous and stable power supply, stable connectivity, and linkages to data centers—which can only be achieved through collaborative efforts among different government institutions in peacetime.

The ongoing conflict in Sudan has both political and economic drivers and poses significant commercial challenges to the agrifood system’s private sector and traders. In view of the conflict, the vertically integrated monopolies by the SAF-RSF and their dominance in the financial sector, productive sectors, and in trade exacerbates the crisis for domestic non-military food value chain actors. Promoting more robust competition is crucial to reviving the agrifood sector and is contingent on dismantling the SAF-RSF monopolies in the agrifood system (imports of agricultural inputs and distribution, control over market prices, livestock exports, and gum Arabic exports; among others), and streamlining value chain processes. Thus, funding and financing of the peace process should include private sector investments, with measures such as longer grace periods for finance and lowered transaction costs to get agri-processing firms up and running again.

Oliver K. Kirui is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development and Governance Strategies (DSG) Unit, based in Khartoum, Sudan; Khalid Siddig is a DSG Senior Research Fellow and Leader of IFPRI’s Sudan Strategy Support Program; Hala Abushama is a DSG Research Assistant, based in Khartoum; Alemayehu Seyoum Taffesse is a DSG Senior Research Fellow and Ethiopia Program Leader. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed.

Referenced working paper:

Kirui, Oliver K.; Siddig, Khalid; Abushama, Hala; and Taffesse, Alemayehu Seyoum. 2023. Armed conflict and business operations in Sudan: Survey evidence from agri-food processing firms. Sudan SSP Working Paper 11. Khartoum, Sudan: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.136835

This paper was prepared with the gracious financial support of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).