In Papua New Guinea (PNG), rural communities play a crucial role in shaping the country’s agricultural landscape and food security. To better understand these dynamics, IFPRI conducted a Rural Household Survey between May and December 2023 that aimed to gain a clearer picture of rural livelihood structures, food security status, and nutrition trends. We outlined some initial takeaways in an earlier blog post. Here we explore the results in more detail, finding an array of serious food security challenges.

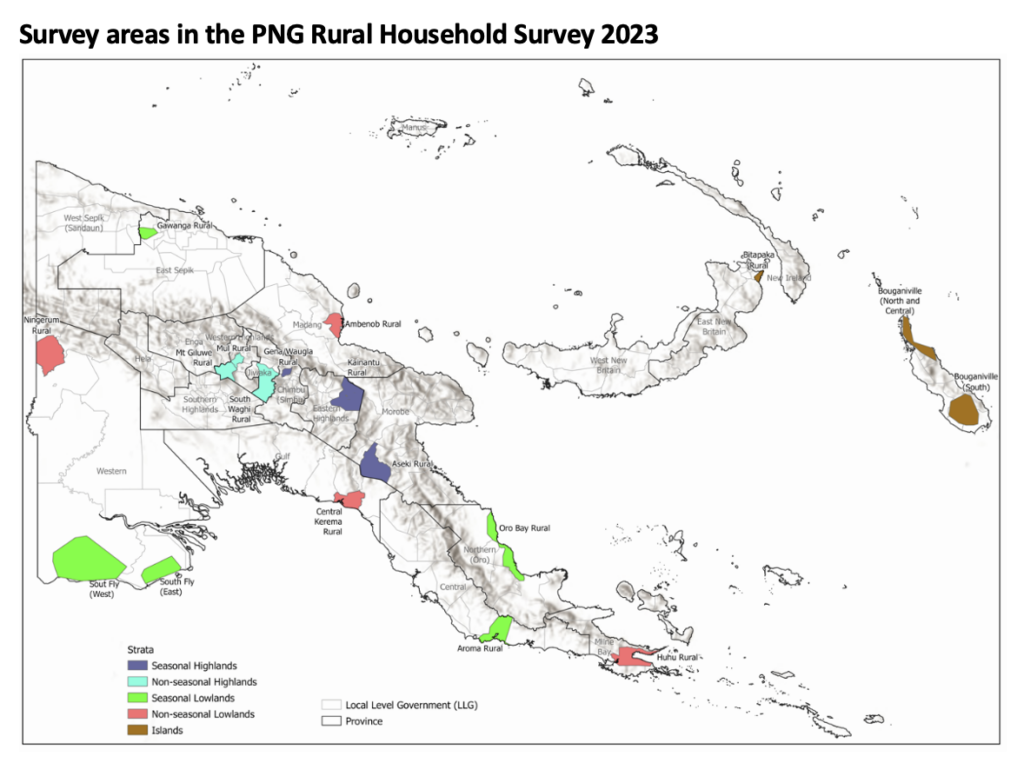

The survey collected data from 2,699 households across 270 communities and 14 provinces. By focusing on five diverse agroecological zones, characterized by elevation and rainfall patterns, the survey sheds light on differences in household welfare and livelihoods across diverse geographies in PNG (Figure 1).

Figure 1

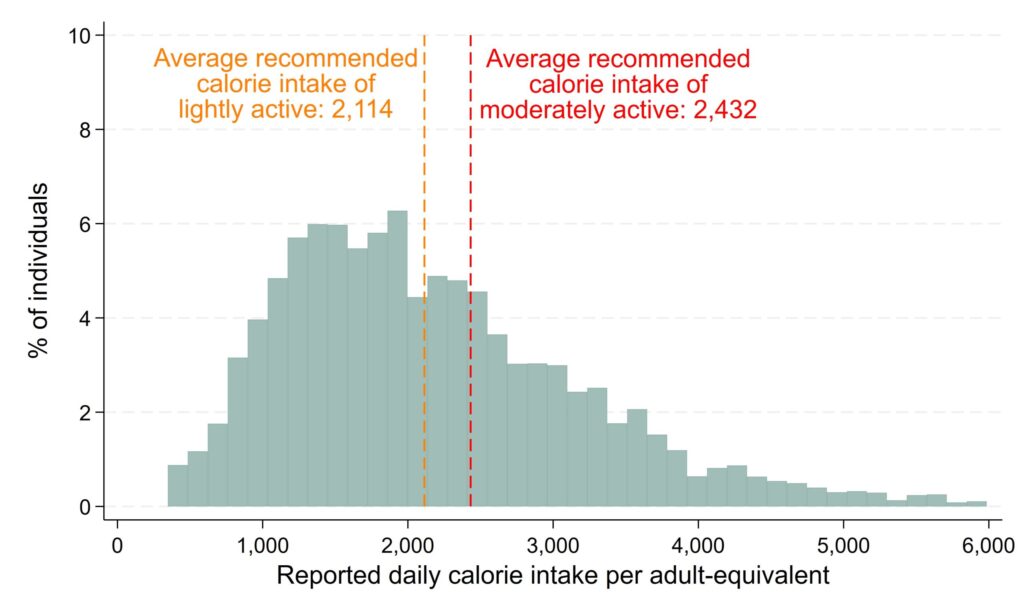

A detailed discussion of methodology and sampling can be found in the recently published 2023 Rural Household Survey Report. A key finding from the survey analysis is that an important share of rural households in PNG face food insecurity. Upon comparing the estimated calorie intake reported by surveyed households with a minimum calorie threshold based on PNG body stature, we found that only 45% of households consume a daily calorie amount that meets the recommended calorie threshold for a lightly active individual. An even smaller share of the survey sample (35%) meets the recommended calorie intake for a moderately active individual (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Reported daily calorie intake per person in Rural Household Survey

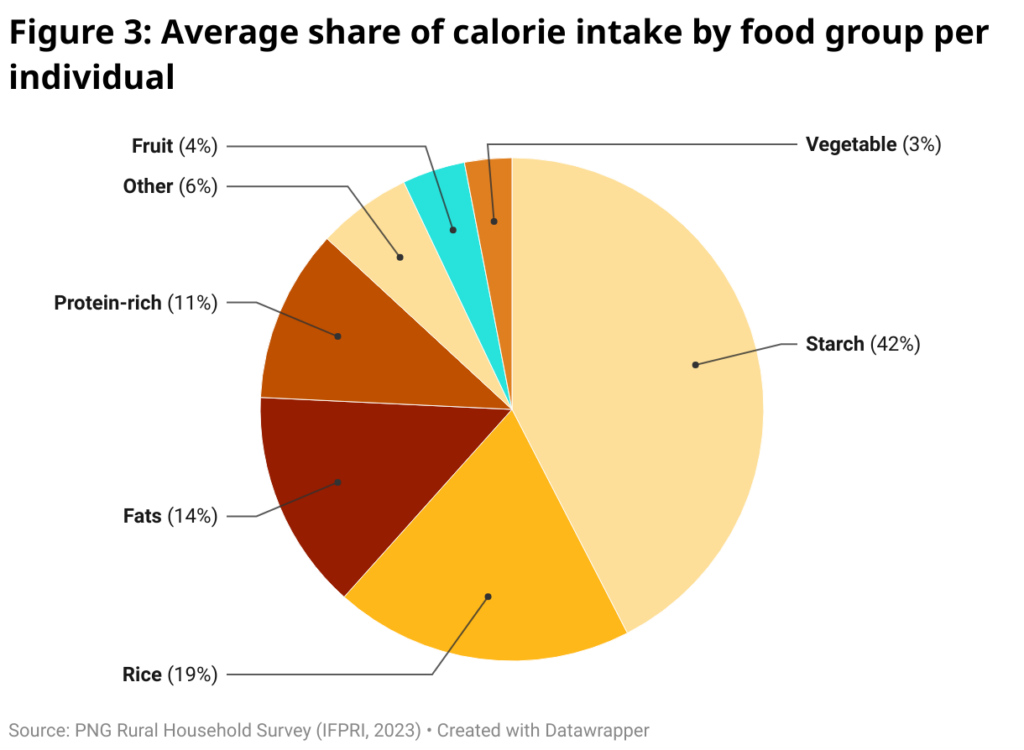

Sufficient calorie intake is important for a healthy lifestyle, but calorie quality and dietary diversity are similarly important. Evaluating the calorie intake by food groups suggests that rural diets are overly dependent on staple-starch based foods such as roots and tubers (for example, sweet potato, taro, cassava and yam) and grains (predominantly rice in PNG). Although starch-based foods are calorie-dense, they lack the nutrient diversity provided by a more balanced diet that also includes vegetables, fruits and protein-source foods.

Currently, almost two thirds of the calories consumed in the average rural diet come from starchy roots and tubers or rice, while more than a quarter of individuals live in households with inadequate protein intake. An alarming 58% of individuals living in lower-income households (bottom 40% of income distribution) do not consume enough protein (Figure 3). Food intake shares differ by geographic region and household income status. These dynamics can be studied in more detail using the 2023 PNG Rural Household Survey Graphing Tool, which explores household consumption and expenditure data and other specific data on rural livelihoods and welfare by study area and economic status.

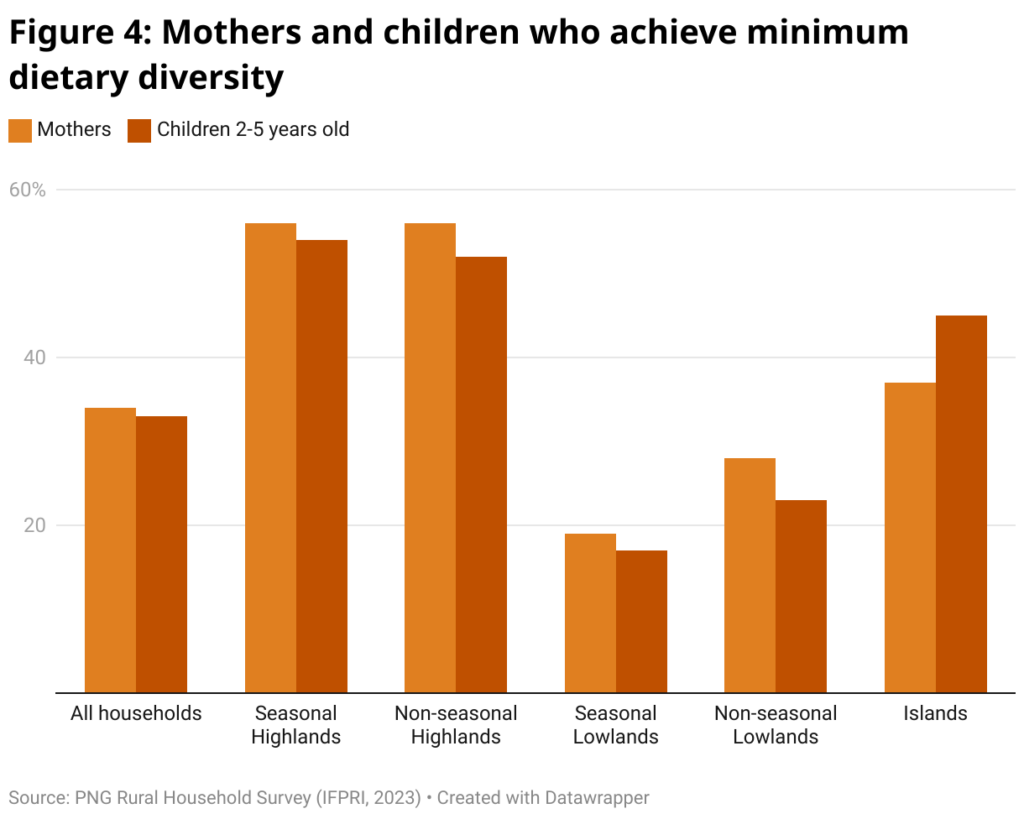

The survey data also collected individual-level information on food groups consumed during the previous 24 hours. A dietary diversity questionnaire sought to understand individual consumption trends in mothers and children between two and five years old, respectively. We evaluated two important dietary diversity indicators: Minimum Diet Diversity (MDD) and Food Group Adequacy (FGA) scores for both groups. While MDD determines whether an individual consumes five out of ten pre-defined food groups during the previous day, FGA is a more stringent indicator requiring individuals to consume all five food groups over 24 hours recommended for a healthy diet. According to the survey findings, only about one-third of mothers and children consumed diets that were micronutrient adequate, as per the MDD indicator. A lesser share (only 11% of mothers and 10% of children aged two to five years) were food group adequate, meeting the FGA target. Differences exist across survey areas; for example, over 50% of mothers and children in the Highlands sample areas meet the minimum dietary diversity requirement (Figure 4).

Over half of the food consumed in sample households is own-produced, signifying the importance of subsistence agriculture in rural PNG. However, agriculture production data suggest that households grow a limited variety of foods. While 93% of households grow at least one vegetable, most households only grow three vegetable types: Leafy greens (89%), green beans (64%), and pumpkin (51%). Less than 20% of households grow any other type of vegetable. This requires households to supplement their diets with purchased foods, which is common across the globe, both in low- and high-income countries. But the market for surplus vegetables, fruits and animal-source protein food groups remains limited due to a variety of bottlenecks in PNG’s agricultural value chains. The 2023 PNG Rural Household Survey Graphing Tool explores more agriculture production and sales trends by geographic area in PNG.

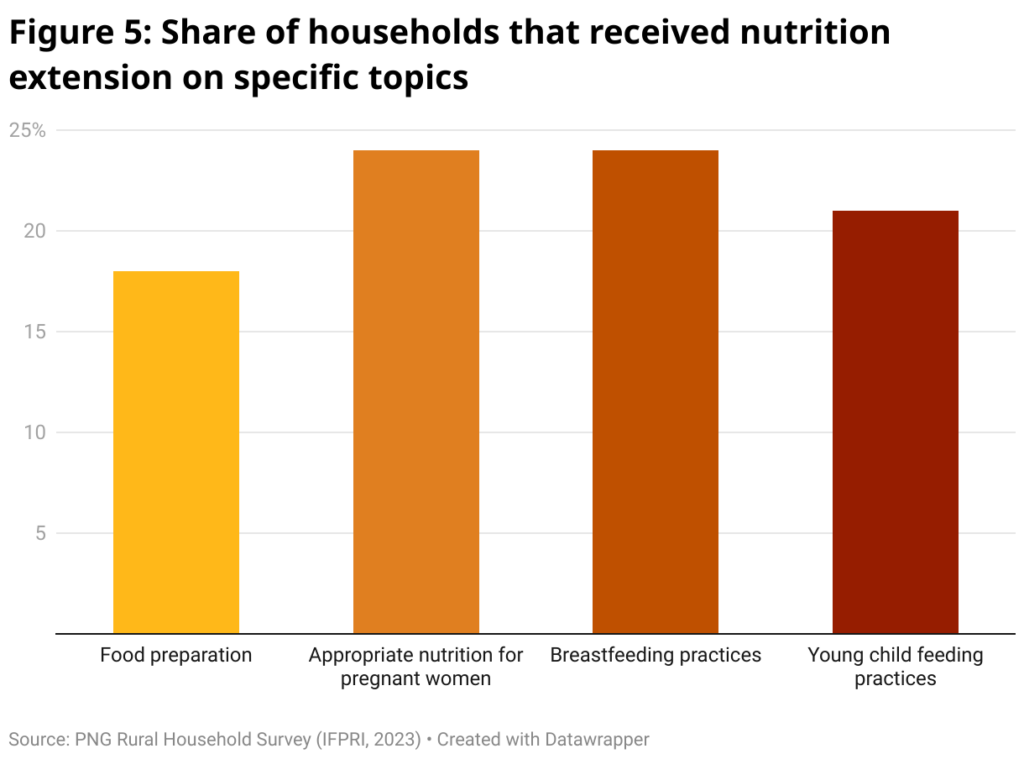

Finally, the survey findings indicate that a greater focus could be placed on educating both men and women on the importance of a nutritious diet for better health outcomes. The survey data revealed that less than a quarter of the sampled rural households received extension information about appropriate nutrition for pregnant women (Figure 5). A lesser share of households reported receiving information about the importance of balanced diets for young children from infancy through five years old.

The household survey analysis suggests that there remains a significant food and nutrition security challenge in PNG. The recently endorsed National Agriculture Sector Plan outlines a roadmap to strengthen PNG’s agricultural export performance. In doing so, there are countless opportunities to strengthen the country’s domestic food production and sales to ensure every citizen in the country has access to reliable food sources that meet both quantity and quality guidelines and therefore promote a healthy lifestyle.

Emily Schmidt is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance (DSG) Unit; Rishabh Mukerjee is a DSG Research Analyst. This post first appeared on the Devpolicy Blog.

Funding for this work was provided by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). This post has been prepared as an output of the Papua New Guinea Agriculture, Food, and Nutrition Policy Support Program (PNG-AFNP) and has not been independently peer reviewed. Any opinions expressed here belong to the authors and are not necessarily representative of or endorsed by IFPRI or the funding providers.