This post is part of a series examining key issues involving climate and agrifood systems tied to the 2023 UN Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai (November 30-December 12). To learn more about IFPRI’s engagement at the Conference, visit our COP28 Spotlight page.

Evidence suggests a strong link between the quality of school meals, children’s health, and both nutrition and education outcomes. School meal programs also have broad food system impacts, and thus are increasingly being designed to include objectives related to smallholder agriculture and environmental sustainability—a topic explored in a new White Paper from the School Meals Coalition on Unlocking Opportunities of Planet-Friendly School Meals, presented at the COP28 Climate Conference in Dubai on December 8.

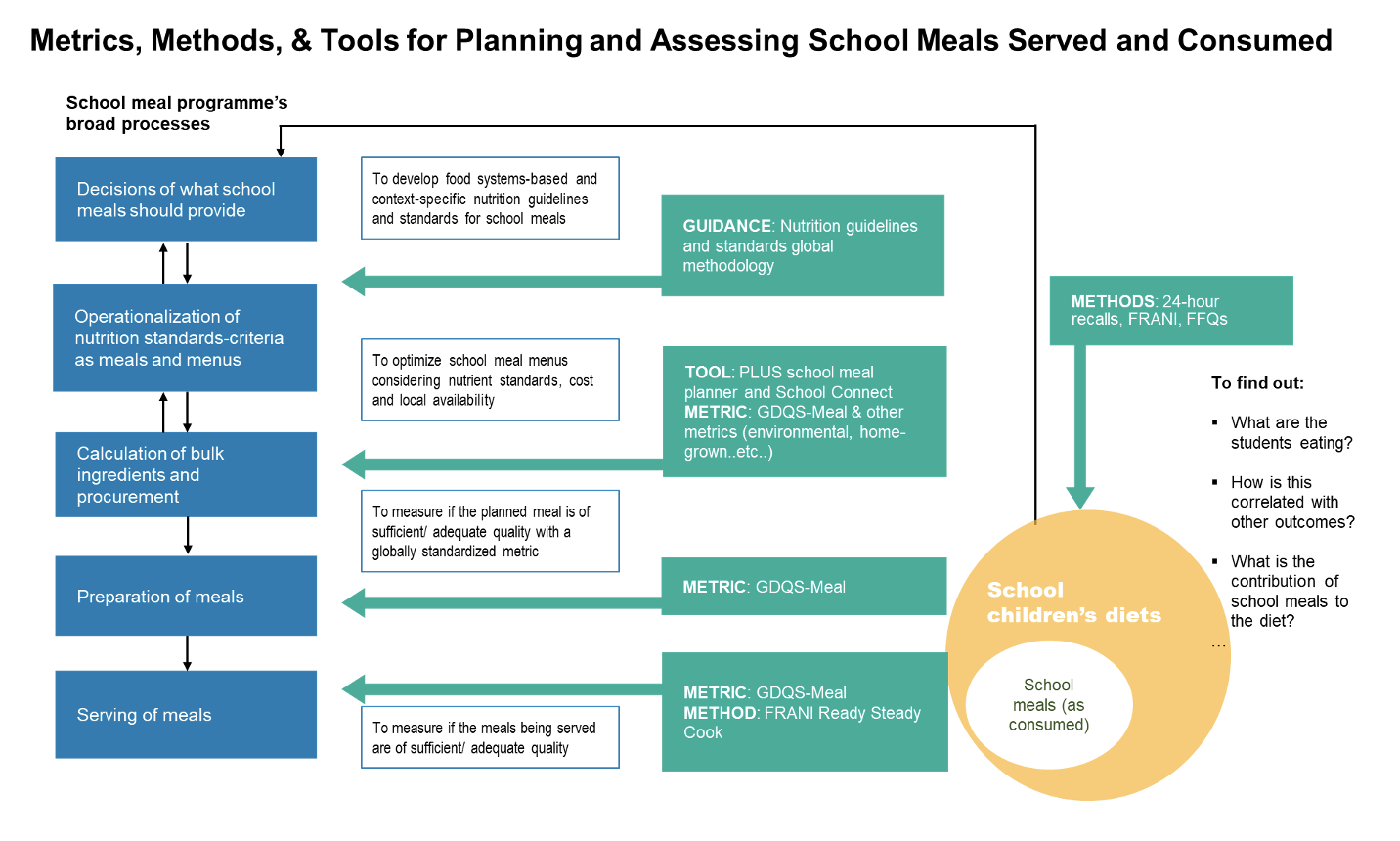

IFPRI was pleased to contribute to this important report by looking at how a widely used existing school meals framework (Galloway, 2010; Fernandes et al., 2016) could be extended to optimize school meal programs to meet food and nutrition quality requirements, alongside food safety, cost, smallholder sourcing and environmental considerations (Figure 1). While this is a promising approach, some areas require greater deliberation, development of metrics, and ultimately careful cross-sectoral coordination to manage decisions on the key trade-offs involved.

Figure 1

Source: Adapted from Galloway, 2010.

The starting point in this process involves setting the quality standards or requirements for the school meal service. Typically, these will include information on food- and nutrient- based targets for the meals.

Food-based targets build on dietary guidelines designed to promote healthy food choices. These include diets associated with improved health outcomes and protection against diet-related non-communicable diseases such as diabetes (WHO, 2021).

Nutrient-based targets reference the daily macro- and micronutrient intake requirements in specific age groups and populations, also known as nutrient reference values (NRVs). NRVs are used to assess population groups’ nutrient intakes, and to design interventions where those fall short. Various sources exist for NRVs, and recent research efforts focus on proposing a set of harmonized NRVs for populations (Allen et al., 2019). Such standards can also be extended to include targets for food safety, costs, smallholder sourcing and environmental footprint.

Once targets are set, the next step is operationalizing the standards in developing meals and menu plans. This first entails developing a food list—including a database with information on food composition and food groupings, seasonal availability, food prices, costs of transportation and storage, and cooking facilities.

Other important elements to consider include food safety measures and equipment (e.g., refrigeration) as well as metrics on the viability of smallholder sourcing and environmental footprints. It’s important to note that obtaining reliable metrics for some of these dimensions may be challenging, and remains an important area of ongoing research, including the development of the Environmental Impact of Diets (EIOD) metrics

Developing menus and meal plans involves building recipes based on food list items that also account for local preferences and acceptability, as well as preparation time and costs.

Once completed, menus and meal plans can undergo optimization analysis, employing linear programming to identify solutions that balance the different dimensions covered by the meal quality standards, and to examine the influence of different constraints (Eustachio Colombo et al., 2019). Once reviewed and validated by nutritionists and other program specialists, the menus and meal plans can be operationalized and integrated into school meal program implementation. This typically entails developing training materials for school caterers, including recipes and handy measurements to be used when serving the school meals.

The last step in the cycle centers on monitoring the quality of the meal service provision, including data on financial flows, food procurement, meal quality and quantity, food safety, prices (food and non-food) and financial and opportunity costs (Gelli and Suwa, 2014) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Stylized view of key process for monitoring school meal quality and the school meal data chain. GDQS: Global Diet Quality Score; FFQ, Food frequency; FRANI, Food Recognition and Nudging Insights. Source: Adapted from IFPRI, Intake, FAO, U. of Ghana, 2022.

Looking forward, this work shows the importance of setting school meal programs in broader food system contexts. Integrating the environmental sustainability perspective into existing methods and metrics developed to support the design, implementation and monitoring of school meal programs remains an important area of ongoing work.

Aulo Gelli and Marie Ruel are Senior Research Fellows with IFPRI’s Nutrition, Diets, and Health Unit. This post is based on IFPRI contributions to Chapter 4 of the White Paper.

Referenced White Paper:

Pastorino, Silvia; Springmann, Marco; Backlund, Ulrika; Kaljonen, Minna; Singh, Samrat; Hunter, Danny; Vargas, Melissa; Milani, Peiman; Bellanca, Raffaella; Eustachio Colombo, Patricia; Makowicz Bastos, Deborah; Manjella, Aurillia; Wasilwa, Lusike; Wasike, Victor; Bundy, Donald AP; (2023) School meals and food systems: Rethinking the consequences for climate, environment, biodiversity, and food sovereignty. Discussion Paper. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.04671492

This work was supported by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) under the project titled, “Learning Support for a Sub-Saharan Africa Multi-Country Climate Resilience Program for Food Security”, and by the donors who fund the CGIAR Research Initiative on Fragility, Conflict, and Migration, through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund: https://www.cgiar.org/funders/