The armed conflict that erupted in Sudan in April 2023 has had severe implications for the country’s economy. With disruptions in infrastructure, trade, and agricultural activities, the conflict has led to scarcity of goods, increased food prices, and reduced economic growth.

These disruptions have reduced the availability of essential food items and triggered a surge in food prices. Agricultural and industrial production in conflict-affected areas has significantly dropped, and the movement of production inputs and goods has been constrained. Smallholder farmers, who rely on access to inputs and functioning institutions, have been heavily affected. The conflict has also led to the displacement of people, putting additional pressure on food resources and public healthcare systems in other states across Sudan.

In a recent working paper, we outline the use of satellite data, specifically tropospheric nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions, to monitor and analyze the impact of the conflict on economic activities in Sudan, showing how it can provide detailed insights on the unfolding effects of conflicts and other shocks.

Nitrogen oxides (NO2 and NO) are harmful air pollutants primarily emitted from anthropogenic activities including industrial processes, power plants, and vehicles, and natural processes such as wildfires, lightning, and microbiological processes in soils. NO2 concentrations in the atmosphere can thus serve as an indicator of human and economic activities. Elevated levels of NO2 are often found in densely populated urban areas with industrial zones and heavy traffic. By mapping and monitoring NO2 hotspots over time, policymakers can make informed decisions about land use, transportation infrastructure, and emission control measures.

To assess the situation in Sudan, we used the Sentinel-5P OFFL NO2 data product, derived from satellite observation, which provides measurements of atmospheric NO2 levels in close to real-time. The product is primarily a tool for monitoring air quality and is commonly used as an indicator rather than a direct measure of human and economic activities. Using NO2 data to detect changes in those activities thus offers a creative way to gain insights into the impacts of an evolving conflict.

The relevant data is collected by the Sentinel-5P atmospheric monitoring satellite, its mission a collaboration between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the European Commission. The satellite carries a state-of-the-art imaging spectrometer, the Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI), that provides highly accurate and detailed measurements of atmospheric gases, including NO2.

To analyze the impact of the conflict, we created a baseline map of Sudan for 2022, marking the locations of concentrated human and economic activity and calculating average annual NO2 concentrations. We then generated a series of maps focusing on April 2023, before and after the April 15 outbreak of the conflict. These maps enabled us to show evolving NO2 concentrations in various regions and cities, and to identify differences between areas affected by the war and those unaffected.

By analyzing NO2 data before and after the onset of the conflict, we observed significant changes in NO2 concentrations in Sudan. Prior to the conflict, NO2 levels were high in urban areas, indicating active economic centers. But after the conflict erupted, NO2 concentrations decreased, particularly in conflict-affected regions like Khartoum. This decline can be attributed to reduced economic activities, limited movement of people and goods, and infrastructure damage.

For example, Figure 1 shows a clear difference between emissions before and after the outbreak of the conflict, with areas around Khartoum (red area center right) and to the south showing noticeably reduced NO2 concentrations after the conflict began.

Figure 1: NO2 levels (mol/m2) in Sudan before and during conflict

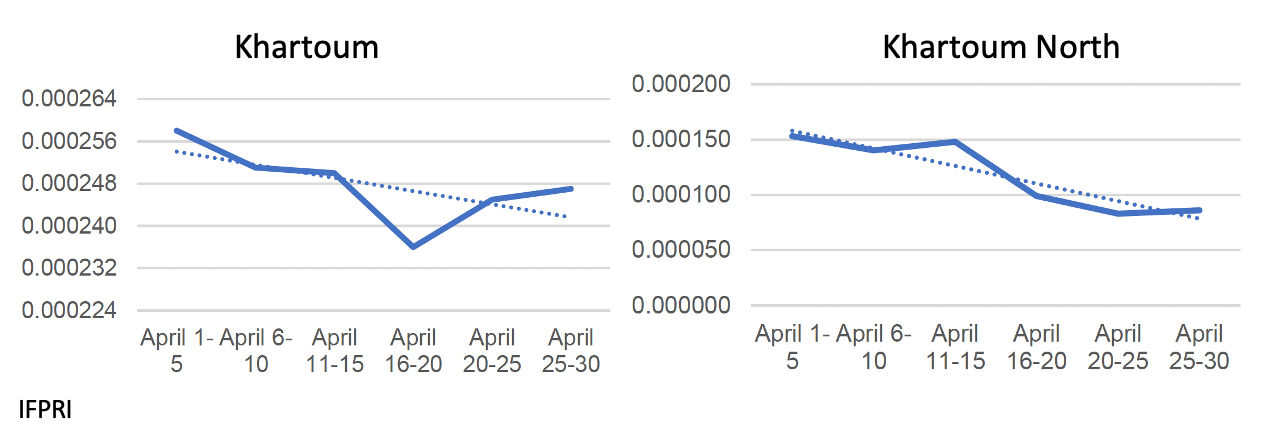

Zooming in, Figure 2 shows declining concentrations in two areas of Khartoum around the start of the conflict, indicating the abrupt stoppage of movement of people in and around the capital reduced economic activities and NO2 emissions.

Figure 2: NO2 levels (mol/m2) in Khartoum and Khartoum North (areas experiencing conflict)

The data also show rising NO2 concentration in regions less affected by conflict compared to Khartoum state—Ed Damazin, Kadugli, and Kassala—during the latter half of April. These areas are farther from the conflict zone and experienced relatively more movement than usual. Thus the higher NO2 concentrations likely reflect the migration of people from Khartoum to safe locations.

Our results show how satellite data, such as NO2 measurements, can provide valuable insights into the environmental and economic consequences of conflicts. By monitoring changes in NO2 emissions, stakeholders can assess the extent and duration of conflicts, understand the impact on economic activities, and make informed decisions for sustainable recovery and stability. However, it is essential to consider the limitations and external factors that can influence NO2 concentrations, such as climate conditions and natural processes.

Satellite data analysis, particularly using tropospheric NO2 emissions, offers a valuable tool for monitoring economic activities during conflicts. In the case of Sudan, the analysis of NO2 changes before and after the conflict provides insights into the disruption of economic activities, reduced movement of people and goods, and the overall impact on food security and livelihoods. By leveraging satellite data, policymakers and humanitarian organizations can better understand and address the economic consequences of conflicts, contributing to more effective crisis response and recovery efforts in Sudan.

Hala Abushama is a Research Assistant with IFPRI’s Development and Governance Strategies (DSG) Unit, based in Khartoum, Sudan; Zhe Guo is Senior GIS Coordinator with IFPRI’s Foresight and Policy Modeling (FPM) Unit; Khalid Siddig is a DSG Senior Research Fellow and Leader of IFPRI’s Sudan Strategy Support Program, based in Khartoum; Oliver Kirui is a DSG Research Fellow, based in Khartoum; Kibrom Abay is a Country Program Leader and DSG Senior Research Fellow, based in Cairo; Liangzhi You is an FPM Senior Research Fellow. This post is based on research that is not yet peer reviewed.

Referenced Working Paper:

Abushama, Hala; Guo, Zhe; Siddig, Khalid; Kirui, Oliver K.; Abay, Kibrom A.; and You, Liangzhi. 2023. Monitoring indicators of economic activity in Sudan amidst ongoing conflict using satellite data. SSSP Working Paper 7. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.136724

This work was supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).